A county in Utah wants to suck 77 million gallons a day out of Lake Powell

In its current design, the Lake Powell pipeline will transport nearly 77 million gallons a day to Washington County in Utah. (Dec. 4, 2017)

- Share via

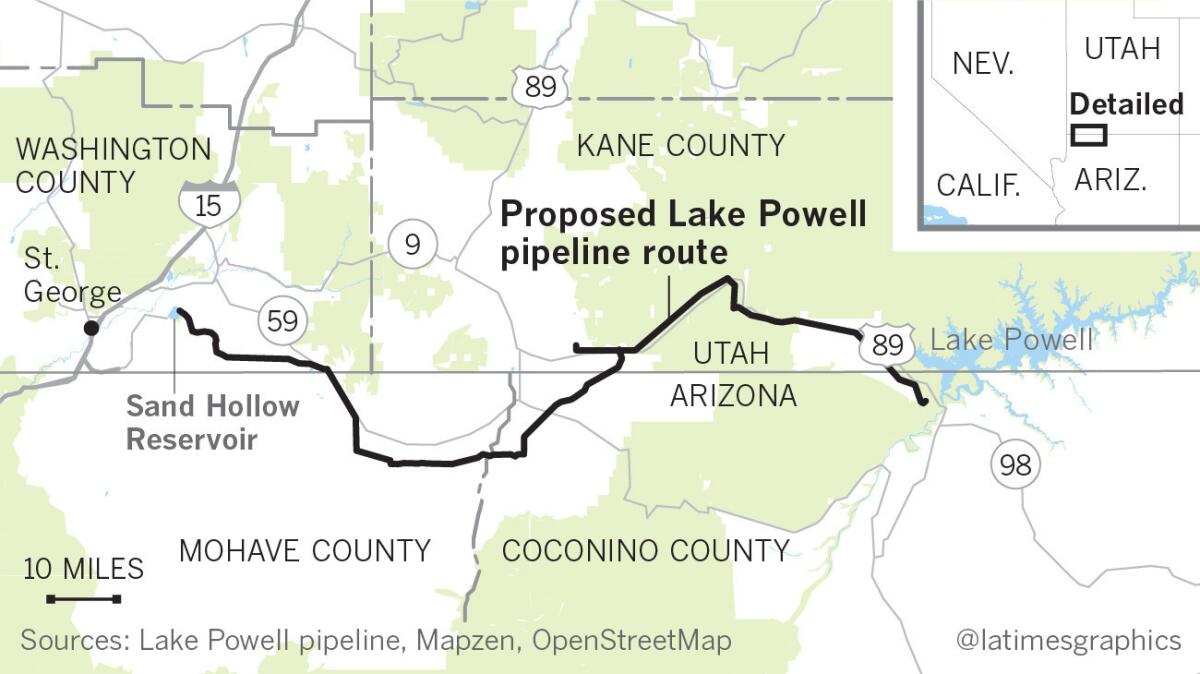

Sun-scorched desert mesa, 140 miles of it, lies between Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir, and Utah’s Washington County, one of America’s driest metropolitan regions.

It’s a long way in miles — but not insurmountable to the Washington County Water Conservancy District, which is charged with ensuring a rapidly growing desert community has water. The district plans to link the reservoir and the county with one of the longest and most expensive water pipelines ever proposed in the West.

Ample sunshine and less than 8 inches of rain a year have proved so attractive that a seemingly ceaseless wave of residential and retail construction blankets the desert near here and climbs to the summits of the region’s red rock buttes.

Since 1990, Washington County, 90 miles east of Las Vegas, has more than tripled in population to 165,000 residents, many of them living in St. George and its rapidly growing suburbs. Demographers project that 400,000 more people could arrive by 2060.

The 140-mile-long Lake Powell pipeline is what state planners see as the best way to avoid a water shortage calamity.

Almost 30 years after county and state water managers introduced the idea — and three years after it was initially scheduled to be completed — the mega water transport plan is finally inching toward its first significant regulatory decision.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which is overseeing the pipeline proposal, is weighing whether to start a two-year study of the environmental consequences of construction and operations on the project’s route through four counties in Utah and Arizona.

The long regulatory process is emblematic of the uncertainty and unending impediments that characterize water pipeline development in an era of a warming climate and more frequent droughts.

Even in the 20th century, when city leaders worked with federal agencies to shift water from river basins to build the region’s growing desert cities, it took decades to get a big water transport project built. The Central Utah Project, a network of tunnels, pipes, canals, pumps and reservoirs that supply water from the east side of the Wasatch Front to the Salt Lake City area, was authorized by Congress in 1956 and still is not finished.

In its current design, the Lake Powell pipeline will transport 86,000 acre-feet — nearly 77 million gallons a day — from an intake 1,200 feet upstream of Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona to Washington County’s Sand Hollow reservoir.

The 69-inch diameter pipeline will have five pumping stations to push water 2,000 feet uphill, and six turbine stations to produce about 45 megawatts of electrical generating capacity. Most of the water will be used by Washington County. Neighboring Kane County will receive roughly 5%.

The pipeline would diversify the region’s water supply, which now comes from a single source: the Virgin River.

“These projects take years,” said Ronald Thompson, general manager of the Washington County Water Conservancy District. “You can’t build them in an election cycle. You have to plan decades into the future. You have to be adaptive. That’s what we’ve tried to do here.”

Yet such reasoning has run into a storm of opposition driven by one central assertion: the Lake Powell pipeline is a costly taxpayer burden that is not needed now or in the foreseeable future. Its construction in an era of meteorological disruption in patterns of snow and rainfall, moreover, is seen as a threat to the diminishing water levels in the Colorado River. That crucial waterway supplies Lake Powell and 30 million downstream users in Arizona, Nevada and California. (The three states have not commented on the proposed pipeline.)

“The truth behind the Lake Powell pipeline is that it is a water grab from the Colorado River by firms and agencies in Utah to convince Utahans that we are running out of water. We’re not,” said Zach Frankel, founder and executive director of the Utah Rivers Council, a water research and advocacy group in Salt Lake City funded by foundations, members and events.

“The reality is that St. George and Washington County residents have the highest per-person water use in the United States because they have some of the cheapest water rates in the world. They are wasting a tremendous amount of water there,” Frankel said.

In the arsenal of facts developed by the pipeline’s opponents, several stand out. The Utah Division of Water Resources asserts that St. George and Washington County have achieved a 25% reduction in water use over the last decade; yet per capita consumption is still somewhere between 289 and 325 gallons a day. Up to 70% of that waters lawns, golf courses, parks and cemeteries.

In other desert Southwest cities, consumption is around 100 gallons a day. Per capita water use in Phoenix is 175 gallons per day.

Underlying high water consumption are exceptionally low water prices. The Water Conservancy District charges its wholesale customers $1.04 for 1,000 gallons of water. St. George households pay $24.72 a month for their water meter and receive the first 5,000 gallons a month for no extra charge. The next 5,000 gallons costs $1.18 per thousand gallons.

A family of four in St. George that uses 300 gallons per person per day would pay $1.62 per thousand gallons, or about $50 a month for water, plus the meter fee. A family of four in Phoenix would pay just a few dollars a month more — but for using half as much water.

“It’s much more reasonable and much less expensive to implement serious water conservation measures and to implement water rate changes,” said Lisa Rutherford, a member of Conserve Southwest Utah, an environmental group in St. George. “As the area grows, those two changes by themselves will push water usage down and alleviate the need for any pipeline.”

The Lake Powell pipeline was authorized and its construction will be financed by the state of Utah under a law passed by the Legislature in 2006. It is the first big water project ever undertaken by the state.

Water ratepayers in Washington and Kane counties will start repaying Utah in regular assessments upon completion, through water rate hikes, plus an $8,000 construction fee on every new home, and property tax revenue.

Nobody, though, knows how much the project will cost. An estimate made in 2008 by the Water Resources Division, and another by a consultant in 2015, put the cost between $1.1 billion and $1.8 billion, or as much as $12.85 million a mile. Eric Millis, director of the Utah Division of Water Resources, is sticking with that estimate, as is the project manager, John Fredell, who just supervised development of a simpler, 50-mile water pipeline in Colorado Springs, Colo., that opened in 2016. It cost $825 million, or $16.5 million a mile.

Millis projected that following completion of the pipeline’s environmental study, construction would start in the early 2020s and operations would commence in the late 2020s. If the schedule holds, water will be flowing into Washington County before the trend line for projected population growth collides with any shortage of water supply, said Thompson of the water conservancy district.

Conservation, Thompson said, isn’t an alternative for a region growing so powerfully that it will be ready to pay heavily to avoid running out of water.

“If I turn on the tap, I’ve got to have water. If I had to pay $10 per thousand gallons, I’d pay that in a heartbeat,” he said. “By 2028, if we don’t have it, we’ll be in trouble.”

Schneider is a special correspondent.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.