‘It doesn’t feel as welcoming’: Becoming a U.S. citizen in the time of Trump

- Share via

Reporting from Fort Collins, Colo. — Omar Ibraham, dressed in a dark jacket and pants, heard his name called by the woman who would change his life forever.

He stood up and took a step forward. Ibraham could see the piece of paper she was holding — the one she had warned him just an hour earlier to never laminate. She said that would destroy its power.

Ibraham took a second step. His heart was pounding. Is this really happening? he wondered. He saw the powerful senator, wearing a crisp blue suit, smiling. There was the judge, unmistakable in his black robes, battling a cold. The mayor and a state senator stood beneath a basketball hoop in the gym. There were flags on the wall from dozens of countries. He had noticed earlier that Somalia wasn’t among them.

The 33-year-old Somalian kept walking. All eyes were on him. He was moments away from completing his years-long journey toward U.S. citizenship Friday. The official paper that would prove it was within his grasp. He’d always wanted to be a citizen of the United States, but in recent weeks, he had begun to wonder if the nation wanted him.

A week earlier, President Trump had issued an executive order barring refugees from seven countries — including his native Somalia. That was when his wife and two children, now living in Nairobi, Kenya, found their path to join him in Colorado was frozen.

Ibraham, who is Muslim, watched the news and saw that a mosque had been burned down in Texas last week. Anti-Muslim rhetoric was openly displayed on television and in social media. His wife would sometimes feel down. He said, however, he remained hopeful.

“In the next election, I can vote. As an American citizen, I will try to do good for the United States and work for unity,” he said. “And as a citizen, I can also hopefully help move things forward for my family.”

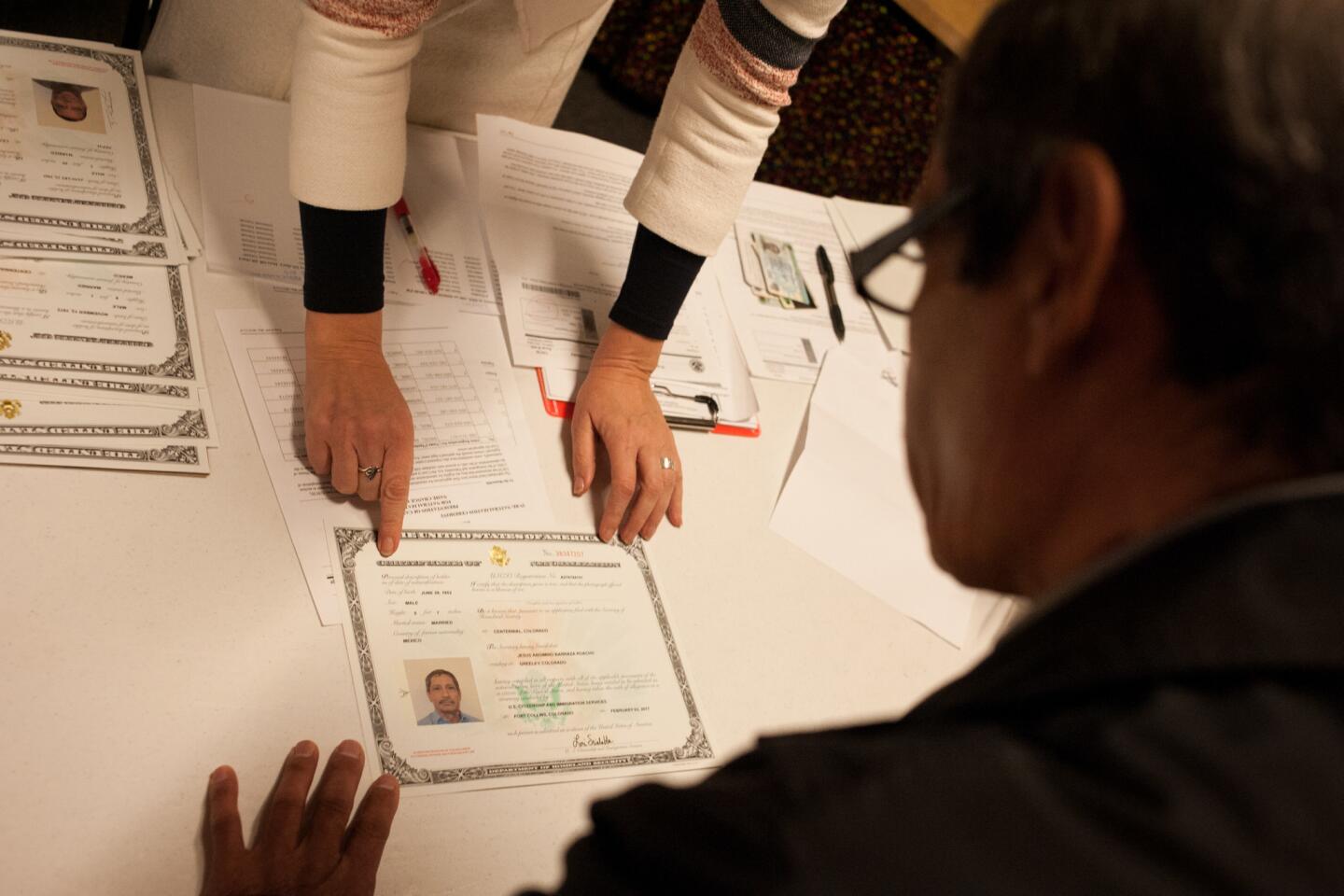

He became a citizen Friday afternoon at Dunn Elementary School, joining 25 others from 13 countries that took the oath and got their official papers. The ceremony — run by Kristi Barrows, director of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ Denver district — featured fifth-graders singing “This Land Is Your Land” and short speeches by U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet (D-Colorado) and Fort Collins Mayor Wade Troxell.

Bennet recalled his family’s immigration history. The senator’s mother was smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto during the Nazi occupation of Poland during World War II. She then immigrated to the United States.

“They were able to succeed beyond their wildest dreams because America welcomed them,” Bennet said. “We welcome them not with prejudice, but with opportunity.”

Sameen Abbasi, a 29-year-old from Pakistan, was excited to join her husband as a fellow U.S. citizen and the couple sought out Bennet after the ceremony to thank him for his statement opposing Trump’s executive order.

Sen. Cory Gardner (R-Colorado) who wasn’t at the ceremony but wrote a letter that was read aloud to the new citizens, reportedly had also criticized the Trump proposal by saying it went too far.

Abbasi, also Muslim, said the process of becoming a citizen had been exciting, but the push by the Trump administration targeting nations with Muslim majorities in recent weeks had dampened her spirits. She said the tone from the White House seemed to be setting people on edge.

“It doesn’t feel as welcoming right now,” she said. “People see me and they know I’m different, but they can’t tell by looking at me if I’m a citizen or not.”

On average since 2010, Citizenship and Immigration Services naturalizes 706,000 people a year in public ceremonies or through small procedures in courts. Mexico accounts for the largest volume of those becoming naturalized, followed by India and the Philippines. Of those countries named by Trump in the executive order, only Iraq and Iran cracked the top 20 for the number of people naturalized — a combined total of about 25,000 people in 2015, according to Homeland Security.

Ibraham said he worried about being targeted for being a Muslim, but he also believed he was better off in the United States than in the refugee camp in Kenya or Somalia, where his family fled from when he was a child.

The camp, he said, was never a home — even though he lived in it for 12 years.

His family was crammed into a temporary shelter that had two rooms — one of which he shared with his brothers. He said sometimes he’d sleep outside, though he said sometimes that would get too hot.

Every other day, he said, they would check a big board in the camp to see if their names were on it — the start of their process of finding a new country. His parents and his three brothers were the first to come to the United States.

He and his sister left the camp together in 2010.

Ibraham remembered his first step onto a hot, crowded bus that took him away from his wife and child and toward freedom. They had been awaiting their chance to leave — eventually relocating to Nairobi to live and wait for notification that they’d been accepted to the United States as refugees. He wept as he waved goodbye to them — their figures disappearing in the distance and dust.

A long flight to Miami followed and then to Fort Worth, Texas — where some of his family lived at the time — before reuniting with his brothers and parents in Greeley, where he is taking classes to become a big rig driver.

The soft-spoken Ibraham remembered what he told his wife before he boarded the bus and after he’d kissed their 1-year-old daughter.

“I am going to the United States and I’ll come back for you,” Ibraham said. “Everything is going to be all right.”

He visited a few years ago, but now he waits and hopes his wife and children can soon join him.

Standing in the gym after Friday’s ceremony, his brother held a smartphone and took a picture with him holding his citizenship papers, a small American flag and a copy of the U.S. Constitution.

His sister called him. Was he a citizen yet?

Yes, he replied, smiling.

Ibraham texted the photo to his wife, who would show it to his daughter, now 7, and his 3-year-old son — the boy and his father have not yet met. He said he would talk to them another time.

His brother gathered up his coat. It was time to go home.

Twitter: @davemontero

ALSO

Trump’s shock-and-awe strategy produces his first major setback

Trump is targeting up to 8 million people for deportation

Trump and Congress may make it easier to get drugs approved — even if they don’t work

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.