Opinion: Obamacare opponents make out-of-context pitch to the Supreme Court

- Share via

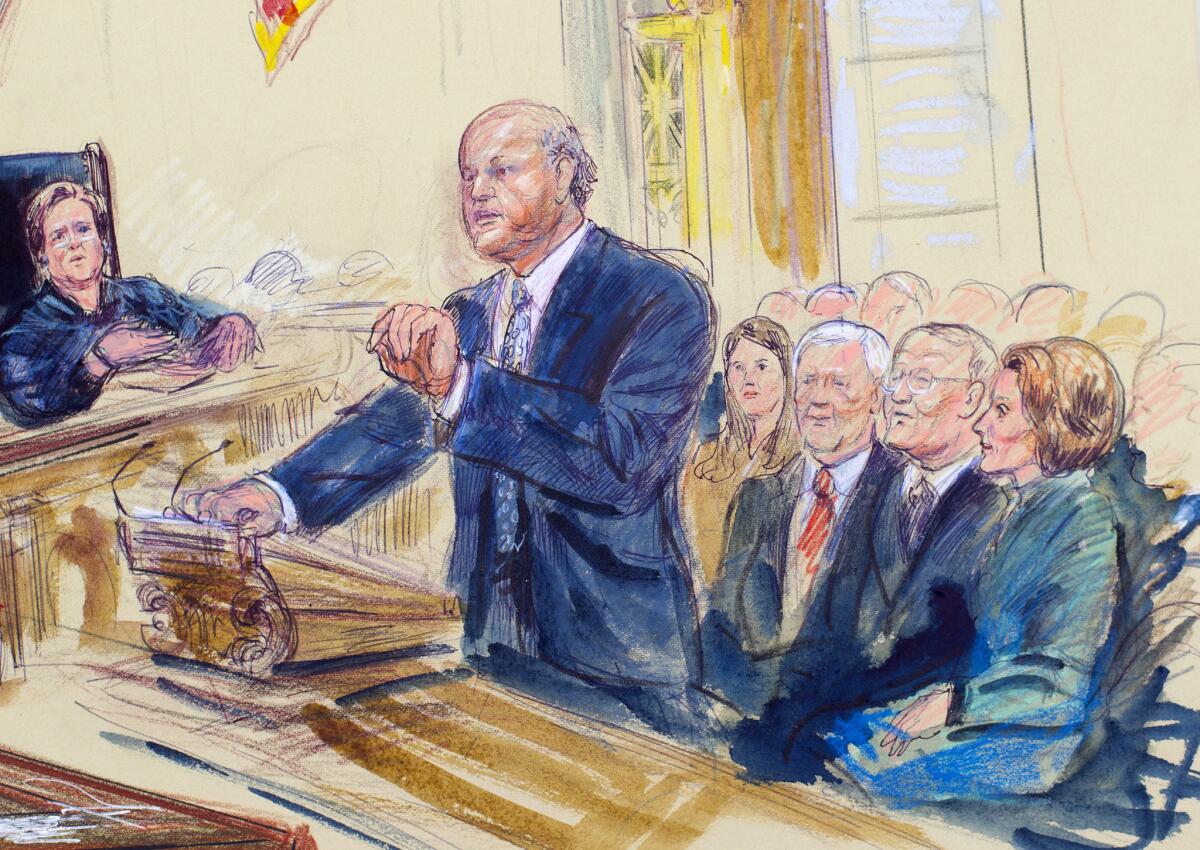

The anti-Obamacare lawsuit the Supreme Court heard Wednesday is based on a false premise, so it’s not surprising that the first point made by the plaintiff’s lawyer, Michael A. Carvin, was false as well.

The false premise is that lawmakers intended to withhold subsidies from states that did not set up their own insurance exchanges as a way to strong-arm them into doing the work. I laid out the actual history of the act in a post last year, but the short version is that such a plan was never even discussed. The closest Congress came to doing so was a preliminary proposal in the Senate that would have withheld subsidies from states that didn’t enact more consumer-friendly insurance regulations, but that idea was dropped by the time the measure reached the Senate floor.

Nevertheless, as Carvin noted, the issue is what the law says, not what its authors intended it to say. And on that issue, he said, “The only provision in the act which either authorizes or limits subsidies says, in plain English, that the subsidies are only available through an exchange established by the state under Section 1311.”

Except that’s not true.

Here’s how the section dealing with subsidies starts. “In the case of an applicable taxpayer, there shall be allowed as a credit against the tax imposed by this subtitle for any taxable year an amount equal to the premium assistance credit amount of the taxpayer for the taxable year.”

That’s the authorizing language that created the entitlement to a tax credit for any “applicable taxpayer.” Later on, the law goes on to define “applicable taxpayer” this way: “The term ‘applicable taxpayer’ means, with respect to any taxable year, a taxpayer whose household income for the taxable year equals or exceeds 100 percent but does not exceed 400 percent of an amount equal to the poverty line for a family of the size involved.”

Other provisions impose limits on the subsidies by barring them for dependents, prisoners and for people in the country illegally, but otherwise there is no restriction on who can receive subsidies. If you meet the income test, you qualify.

The language Carvin referred to is in the Premium Assistance Amount section that determines how to calculate the size of a subsidy. It bases that calculation on the amount paid for a qualifying health plan bought through the newly minted state exchanges, as opposed to one obtained through private exchanges or other sources of insurance.

That’s a very different context than the one Carvin put the disputed phrase into. Under his interpretation, the language sounds like a clear barrier to subsidies for residents of states that don’t set up their own exchanges -- which contradicts what the law actually says about eligibility.

Liberal justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Elena Kagan called Carvin on that. Said Kagan, “It’s put in not in the place that you would expect it to be put in, which is where it says to the states, ‘Here is the choice you have.’ It’s not even put in where the statute defines who a qualified individual is or who is entitled to get the subsidies. Rather, it comes in in this technical formula that’s directed to the Department of the Treasury saying how much the amount of the subsidy should be.”

Carvin responded that the provision limiting the tax credits was inserted in the only place that made sense, the part that made changes to the tax code. He also said that if the Internal Revenue Service had gotten its regulations out properly and quickly, states would have been given plenty of notice about the potential loss of subsidies if they didn’t set up their own exchanges.

Kagan and another of the court’s liberals, Justice Stephen G. Breyer, suggested that the Carvin’s point was refuted by another provision of the law, which holds that the state exchanges set up by Washington are equivalent to the ones the states set up for themselves. The court’s fourth liberal justice, Sonia Sotomayor, asked why withholding subsidies and sending a state’s insurance plans into a “death spiral” wouldn’t be unconstitutionally coercive -- the same problem the court cited when it struck down the ACA’s requirement that states expand their Medicaid programs. (Interesting historical note: Carvin had argued that Obamacare case too, representing those who unsuccessfully challenged the law’s individual mandate to buy insurance.) Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, a swing vote on the court, echoed Sotomayor’s concern.

Conservative Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. came to Carvin’s aid on the former point, and fellow conservative Antonin Scalia helped Carvin out on the latter one. If the right interpretation of a statute renders it unconstitutional, Scalia said, there’s no precedent for the court misinterpreting a statute to make it constitutional.

Pressed by liberal justices to show that lawmakers knew about and debated withholding subsidies from some states, Carvin said they didn’t debate it because the text was clear. But that could just as easily prove the opposite. In fact, when he told the justices “there’s not a scintilla of legislative history suggesting that without subsidies, there will be a death spiral,” he was acknowledging that Congress -- which was under constant pressure from insurers to guard against a triggering vicious cycle of premium increases -- never even contemplated withholding subsidies.

Solicitor Gen. Donald B. Verrilli, who defended the Internal Revenue Service regulations that were targeted by the lawsuit, noted that Congress required every state to establish an exchange, but lawmakers knew that the 10th Amendment didn’t allow them to force states to do so. That’s why they included the “state flexibility” provision in the law that gave each state the option of letting the federal government set up its exchange for them. If the plaintiffs were right about states losing their insurance subsidies if they chose not to set up exchanges, Verrilli argued, that would be an “Orwellian” interpretation of “flexibility.”

His arguments drew skeptical responses from Alito and Scalia, who asked why Congress would use the phrase “established by the State” if it meant “established in the state.”

Verrilli countered, “The provision ... doesn’t say ‘established by the State’ with a period after ‘State.’ It says, ‘established by the State under Section 1311 [the section ordering all states to establish exchanges]. And our position textually is -- and we think this is clearly the better reading of the text -- that by cross-referencing Section 1311, effectively what Congress is doing is saying ... ‘Exchanges established through whatever mechanism.’ ”

He added, “Wherever this provision appears in the act, ‘established by the State under Section 1311,’ it’s doing work. And the work it’s doing is saying, ‘What we’re talking about is the specific exchange established in the specific state as opposed to general rules for exchanges.”

Scalia seemed unimpressed. “How can the federal government establish a state exchange? That is gobbledygook,” he said at one point.

Verrilli argued that it was the plaintiffs’ interpretation of the law that really resulted in gobbledygook. “If you read the statute, the language, the way Mr. Carvin reads it instead of the way we read it, you come to the conclusion ... in a federally facilitated exchange, there are no qualified individuals. Therefore, the exchange cannot certify a qualified health plan as being in the interest of qualified individuals because there aren’t any, so there aren’t any qualified health plans that can lawfully be sold on the exchange.”

The court is expected to rule on the case later this term, most likely in June.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.