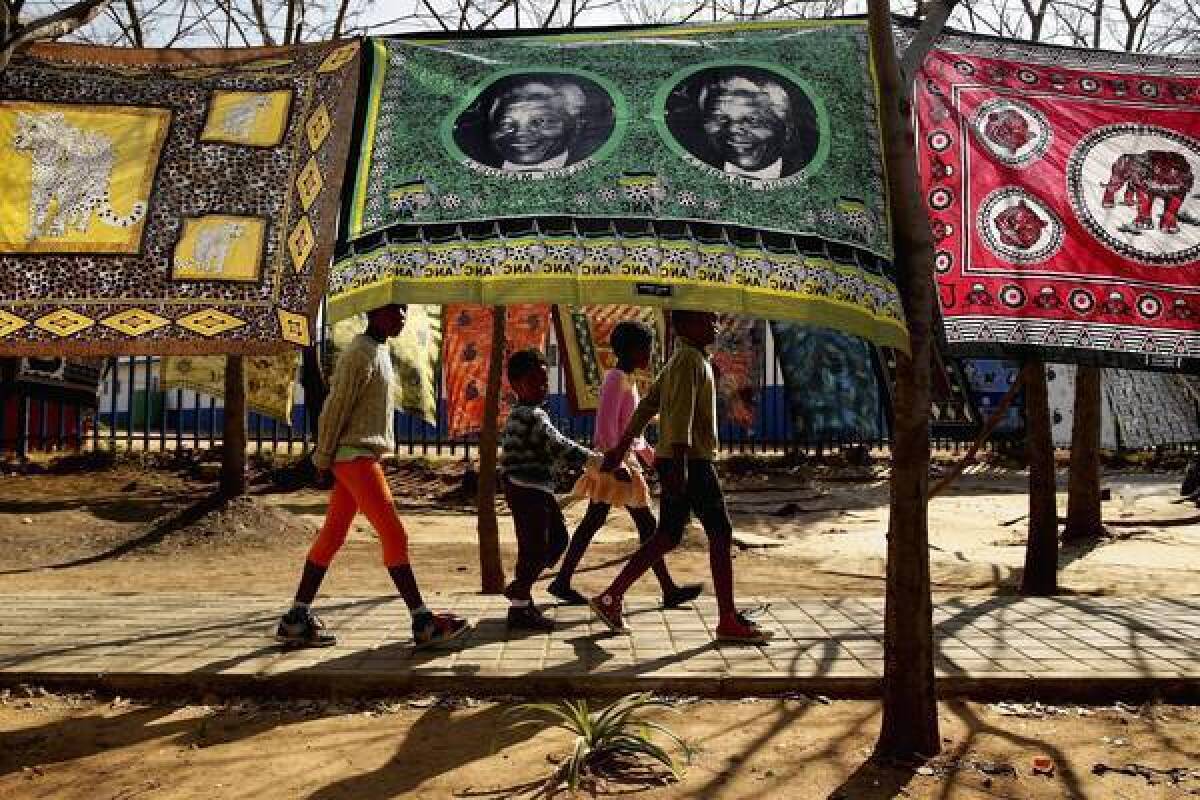

The Obama-Mandela dynamic, reflected in a photo

- Share via

WASHINGTON — One is standing, cutting a tall silhouette the world would soon recognize. The other, an aging icon, rests in a dimly lighted chair with a cane at his side.

On the surface, the photograph of Barack Obama meeting Nelson Mandela for the first and only time appears a passing-of-the-torch moment: the young leader paying homage, the older man imparting wisdom. But the image is not what it seems.

As Obama embarks Wednesday on his first major tour of Africa as president, Mandela, now 94, lies in critical condition in a hospital. The White House is deferring to Mandela’s family on whether Obama should stop by to pay his respects and to cement the connection between two transformational figures, America’s first African American president and South Africa’s first black president.

It is often assumed, and misreported, that the two men met when Obama visited South Africa in 2006. But the meeting occurred a year earlier, when Mandela was in Washington.

Mandela, it turns out, was only vaguely aware of whose hand he was shaking and he initially turned down the visit from the then-new junior senator from Illinois. Obama had detoured to Mandela’s hotel from a meeting in Georgetown.

In some ways the picture parallels their relationship: symbolism overtaking reality. Since Obama entered the White House, he and Mandela have spoken by phone several times in brief private conversations, aides say. But their relationship has been marked more by symbolism than substance.

“My sense is the connection has been slight, but warm,” said Verne Harris, director and chief archivist at the Mandela Center of Memory in Houghton, South Africa, outside Johannesburg. An interview on the relationship, he joked, “shouldn’t take long.”

In his 1995 memoir, “Dreams From My Father,” Obama lists Mandela as one of the male role models who shaped his view of his own absent father, who was born in Kenya.

“It was into my father’s image, the black man, son of Africa, that I’d packed all the attributes I sought in myself, the attributes of Martin and Malcolm, DuBois and Mandela,” he wrote.

And on his 2006 tour of Africa, Obama credited the anti-apartheid movement that spread from South Africa to U.S. college campuses in the 1970s and early 1980s for inspiring his political career.

“If it wasn’t for some of the activities that happened here, I might not be involved in politics and might not be doing what I am doing in the United States,” Obama said at the time.

A younger Obama had a more complex — and conflicted — take on the impact of his college activism.

“It had started as something of a lark, I suppose, part of the radical pose my friends and I sought to maintain, a subconscious end run around issues closer to home,” Obama wrote of his involvement with an anti-apartheid campaign at Occidental College in Los Angeles.

He gave his first speech at a campus rally protesting the college’s investments in companies doing business in South Africa. Obama described the intoxicating experience of commanding a crowd — “I knew that I had them” — and the disappointment of being pulled off stage in a preplanned bit of theater. But despite the rush, he left the experience disenchanted.

“I don’t believe what happens to a kid in Soweto makes much difference to the people we were talking to,” Obama told a friend afterward. “Pretty words don’t make it so.”

Obama’s autobiography makes few other references to Mandela or South Africa, and his eventual path to the White House traveled issues closer to home. He was just five months into his first U.S. Senate term when he met Mandela on May 17, 2005.

That morning, Mandela delivered a speech at the NAACP. He was to meet with President George W. Bush and Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton later in the day, according to Zelda la Grange, Mandela’s personal assistant.

Frank Ferrari, a Mandela associate in the U.S., reached out and asked Mandela to make time for the junior senator from Illinois. With Mandela exhausted and facing two other major meetings that day, “we declined the request to add to his schedule,” La Grange said in an email recounting the incident.

“We were then told that Sen. Obama was expected to stand for the presidential election and he could well become the first black president of the USA,” she wrote. La Grange said she couldn’t remember who offered that description, possibly Ferrari. She didn’t necessarily buy it.

“Personally, I met that prediction with a bit of skepticism,” she said. “But then we agreed that he could pay a courtesy call on Mr. Mandela.”

Obama was riding in his aide’s Volkswagen Passat, headed to a meeting in Georgetown, when his scheduler called and asked whether he’d like to meet Mandela. The aide, David Katz, quickly headed to the Four Seasons Hotel.

The two were met by Mandela’s entourage of aides. Obama greeted them and then walked toward Mandela, who was in an armchair next to a window. Obama extended his hand; Mandela apologized for remaining seated, La Grange said.

Katz, who had grabbed his camera from his car, snapped the picture.

“I thought to myself at the time, well, no one will recognize this silhouette because he’s a junior senator,” Katz recalled. “But someday, if he happens to be president or something, it’ll be recognizable.”

About 10 minutes later, Obama left quietly.

“He was sort of pondering the gravity of what had just happened,” Katz said.

Obama never said much about that meeting. Because his name wasn’t on Mandela’s formal schedule, the moment was lost for years. Harris, the archivist, said he didn’t know the two had even met until 2010, when Obama sent Mandela a signed copy of the photo as a birthday gift.

Mandela, already infirm, asked his staff to place it behind his desk, next to a photo of Muhammad Ali.

“An inspiration to us all!” the inscription reads. Signed, simply, “Barack Obama.”

kathleen.hennessey@latimes.com.

Times staff writer Christi Parsons contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.