Timbuktu calligrapher keeps ancient knowledge alive

In Mali, copying Arabic manuscripts was once a prestigious occupation. Today, it is a spiritual enterprise that speaks to one man’s heart.

- Share via

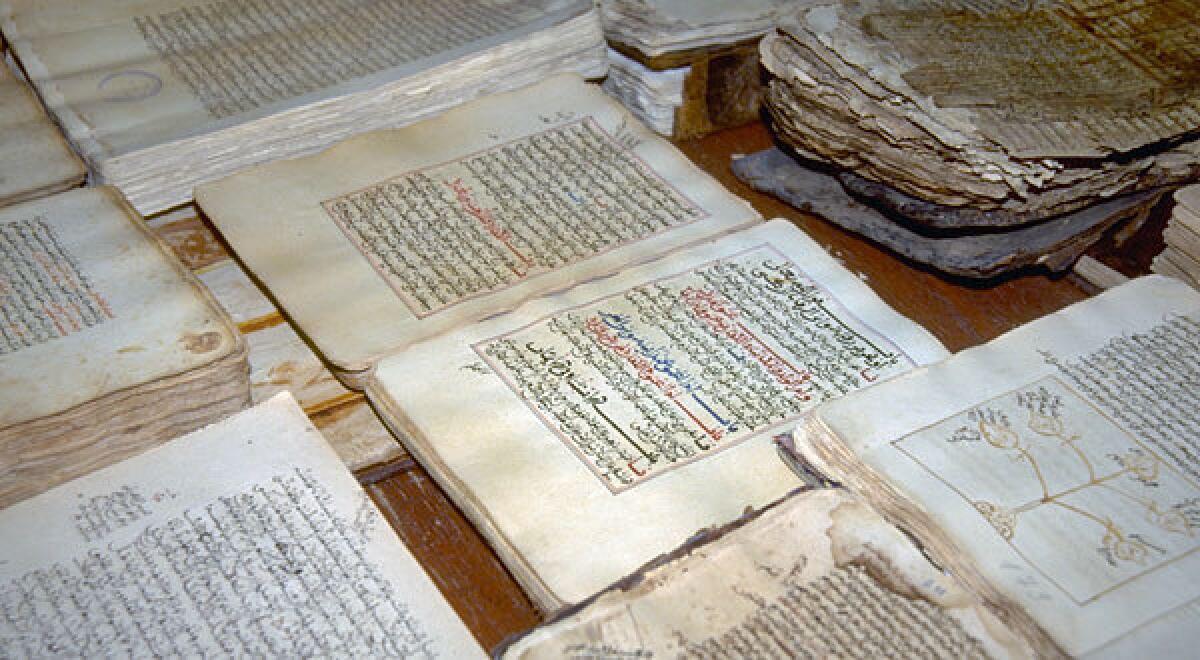

Homemade twig pens stand like off-duty soldiers in a jar on Boubacar Sadeck's worktable. The morning sun steals into a room stuffed with a jumble of papers, ink bottles and stretched animal hides. He sits thoughtfully before a blank sheet of paper, with several old manuscripts — the color of dark tea and covered with Arabic script — open at his side.

Occasionally a breeze wafts in and playfully flicks one of the old brown pages to the floor.

Copying the words of ancient scholars in elegant Arabic calligraphy makes Sadeck feel close to heaven.

"My weakness, my love, is calligraphy," said the scribe, who fled Timbuktu, famed for its collection of centuries-old manuscripts, when Islamist militias invaded last year. "If I go a day without writing, I feel as if something is missing or strange. When I sit down with my paper and my pen, I feel wonderful. I feel at ease."

Copying and recopying old manuscripts is an ancient Timbuktu calling. In the 15th century, there were hundreds of scribes; the job was one of the most highly paid and prestigious occupations in the city, then an intellectual center and trade hub.

Adventurer Leo Africanus described a magnificently furnished court, decorated with opulent objects of gold.

"In the city are many judges, doctors and clerics, all well-financed by the king, who greatly honors lettered men," he wrote. "Hither are brought diverse manuscripts or written books out of Barbary [northern Africa], which are sold for more money than any other merchandise."

Salt comes from the north, gold from the south, money from the white men's country, but God's words, holy things, interesting tales, we can find them only in Timbuktu.

Sadeck, at 38 the youngest of Timbuktu's copyists, doesn't earn much money from his craft. It's his sheer love of the liquid, graceful Arabic script and the meaning of the ancient words that keeps him working — now in Bamako, Mali's capital.

"I found an ancient poem about tea, how to make tea, the ingredients, the importance of tea. At the end, the one who wrote this also gave information about himself. I felt such a close spiritual connection with that writer."

When he fled Timbuktu last April, he carried the family's collection of 80 manuscripts. Now he works in a small, bright studio adjacent to a sprawling garbage dump where goats and donkeys forage.

The militias were driven out of the northern cities by the French and Malian armies in January, but many fear it will be years before life returns to normal in Timbuktu.

A man holds up fragments of burned manuscripts at the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu. As French and Malian troops moved into the city in January to retake it from Islamist militants, the fleeing militants set fire to the ancient texts. (Eric Feferberg / AFP/Getty Images)

The lingering insecurity raises doubts about when or even whether Timbuktu's collection of manuscripts, many thousands of which were smuggled out during the Islamist occupation, can return to its home in the city's Ahmed Baba Institute.

Built by the South African government and opened in 2009, it was supposed to become a state-of-the-art center for international scholars to research the manuscripts. But only 9,000 of the institute's 30,000 manuscripts, some dating to the 13th century, had been catalogued before the Islamists came.

There are other questions, like how old the manuscripts really are, how many survive, and how many were destroyed by the militias before they fled Timbuktu. The militias also destroyed ancient tombs, which they deemed idolatrous, so many believe the manuscripts were burned as un-Islamic. And could the rumors be true that some were rescued only to be sold on the black market?

As Sadeck works in his studio, another small room in Bamako is crammed full with 31 large metal trunks, several of which lie open. Inside, manuscripts are neatly packed. A scent of old paper rises as if blown in from a long-forgotten house.

Mohammed Maiga, 33, a researcher at the institute, stands before the metal boxes, beaming shyly, knitting his hands. They hold a large portion of Ahmed Baba's collection.

After the arrival of the Islamists, he and others loaded the manuscripts into rice bags, strapped them onto motorcycles and ferried them to private houses in Timbuktu. Maiga then loaded the manuscripts into the locked metal boxes and sent them by truck to Bamako. He wrote the box numbers onto a bunch of jangling keys, which he later brought to the capital.

The militants burned an unknown number of manuscripts before fleeing the city; weeks later, the ashes lay in gray drifts in the institute's cathedral-like entry hall, with fragments of burned pages resting like brown moths beside the wall.

Oh you, who go to Gao, make a detour by Timbuktu, murmur my name to friends and bring them the scented greeting of exile which sighs after the ground where his friends, his family, his neighbors reside.

Shamil Jeppie, head of the Timbuktu Manuscripts Project at South Africa's University of Cape Town, works with researchers from Ahmed Baba. He says his team's job is to be empathetic but also skeptical toward claims about the age and value of various manuscripts.

The collection is often called "priceless," implying some manuscripts are old masters. But Jeppie notes that the works haven't been scientifically dated. He believes many may be copies made in recent centuries by calligraphers such as Sadeck as a way of conserving the knowledge contained in much older, decaying manuscripts.

Men walk through the ashes in the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu. Employees of the institute helped hide some of the manuscripts before the torching. (Eric Feferberg / AFP/Getty Images)

"Just before this crisis we were going to take some of these items to Germany for dating of the paper and ink," he said. "In that way, we can establish what they have."

To Jeppie, the collection's real value lies in the ancient knowledge the manuscripts contain and the window they provide onto a golden age in the city, when people shared knowledge by transcribing books, as they do these days by posting information on the Internet. "These are priceless because they can elucidate aspects of African history and world history."

The manuscripts cover centuries of Islamic scholarship on subjects that include religion, medicine, ethics, astronomy, trade, literature and architecture. But mining nuggets of information about a distant past from them is painstaking work.

"The Arabic manuscripts are very hard to translate," Jeppie said. "It's West African Arabic script. It's not standard Arabic. It can be very depressing — it takes so long to work through a tiny section."

Centuries ago, scribes copied books that came to the city, creating the famous Timbuktu manuscripts. Sadeck's solitary work is one of the last echoes of what was then a great enterprise.

Sadeck took up the craft at the urging of his uncle, a well-known calligrapher, and became hooked.

Beautiful writing represents the language of the hand and the joy of the heart.

He works daily transcribing passages from his family manuscripts, reproducing the flowing script using ink he makes from ground charcoal and gum arabic. After mixing the ink, he tests it, letting it dry and rubbing it with his finger, to ensure the ink won't rub off in dusty flakes.

Sadeck used to make a good living selling his creations to visitors in Timbuktu, but tourism fell off after a German visitor was shot dead outside a Timbuktu restaurant and three others were kidnapped by the group Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in 2011. The uprising by Islamist militias last year buried the industry completely. Hotels closed and most of the population fled, leaving Timbuktu a remote and depressed desert outpost.

Even in Bamako, few tourists remain to buy Sadeck's calligraphy.

"Sometimes for two weeks I don't get a penny," he said. "For me the first thing is to love what you are doing. If you have passion, you will get motivation, because nobody else is going to motivate you."

The best way to preserve the manuscripts from termites and decay, he believes, is for their owners to touch them daily, use them, read them and study them.

"If they are packed away in the dark, termites can easily get them," he said. "If you keep your eyes on them, they survive."

Follow @latimesdixon on Twitter

More great reads:

He's 63, she's 22 and the visa official is skeptical

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.