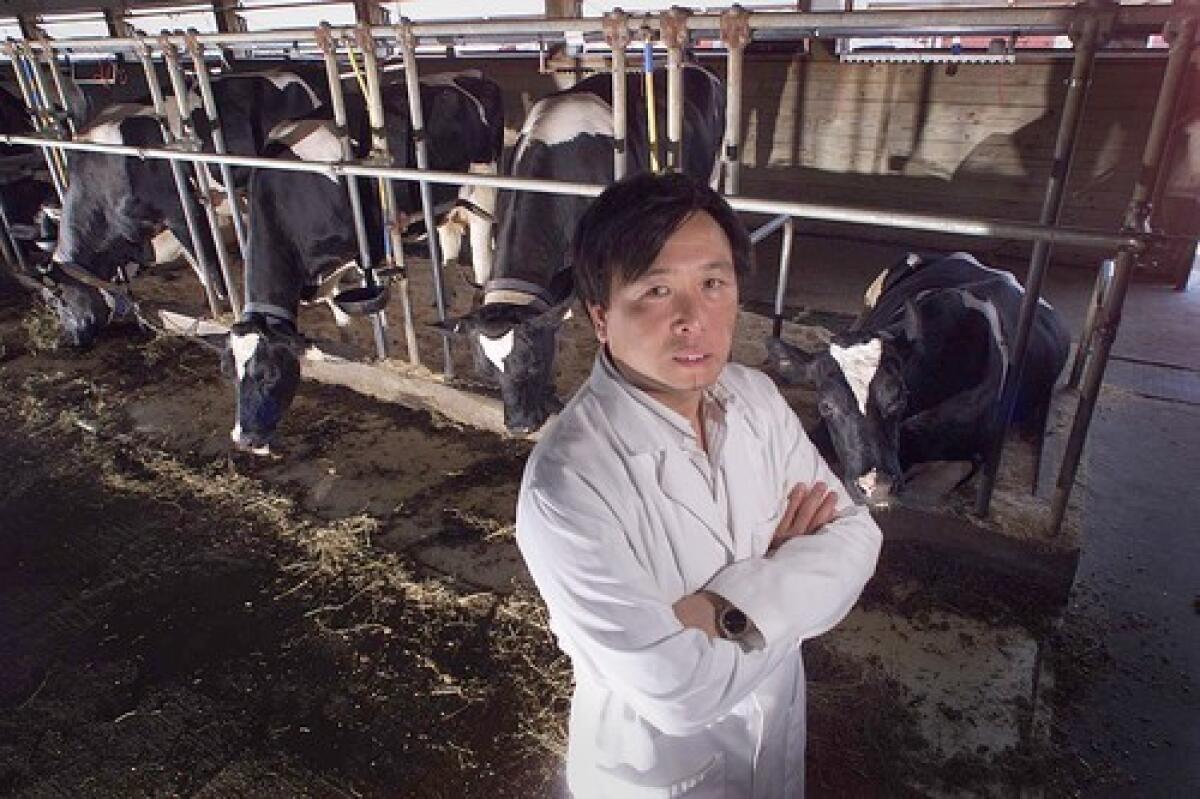

Xiangzhong ‘Jerry’ Yang dies at 49; leading researcher in cloning technology

- Share via

Xiangzhong “Jerry” Yang, who was born in poverty to a family of pig farmers in rural China but escaped to become a leading researcher in cloning technology, cloning the first farm animal in the U.S. and demonstrating the viability of such animals, died Thursday at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston after a long battle with cancer of the saliva gland. He was 49.

Yang worked tirelessly to promote cooperation between U.S. and Chinese researchers, particularly in cloning and other areas of biotechnology, and established a nonprofit company to export cloned embryos from prize dairy cattle to China to increase the supply of milk.

He was also a committed advocate for human cloning as a technique to produce stem cells for medical use.

As a young faculty member at Cornell University in the early 1990s, Yang had tried unsuccessfully to clone rabbits, and he, like many others at the time, had begun to doubt the possibility of cloning using cells from adults.

But the announcement in Scotland on July 5, 1996, that Dolly the sheep had been cloned renewed his vigor, and in 1998, by then working at the University of Connecticut, he collaborated with Japanese researchers to clone six calves from a prized bull.

The next year, he announced the birth of Amy, the first farm animal cloned in the United States.

After the birth of Dolly, there was much speculation among researchers that clones would not have a normal life span because they had shortened telomeres. Telomeres are segments of repetitive DNA on the ends of human chromosomes that protect them from destruction. They get shorter as the cell ages.

Because cloned animals are produced from adult cells whose telomeres have become shortened with age, many suspected that this would limit life span. Yang, however, alleviated this fear by demonstrating that Amy’s telomeres were of normal length.

He was also the first to show that cloned farm animals could successfully reproduce, and his later work was among the research used by the Food and Drug Administration to conclude that such animals were safe to eat.

His ultimate goal was to clone human embryos to treat patients suffering from debilitating diseases such as Parkinson’s and diabetes. His efforts were stymied, however, by the Bush administration’s ban on the use of federal funds for human cloning research and the unavailability of state funds.

To work around these problems, Yang created the China Bridges program to stimulate collaboration in that country, where the rules were not so restrictive. Many of his students returned to China to jump-start the country’s stem cell research efforts, and he recruited international experts to help in the process.

Xiangzhong Yang was born July 31, 1959, in Weixian, Hebei, China. His parents were pig farmers in the tiny village of Dongcun, about 300 miles south of Beijing. The province was suffering from a famine, and the infant became so emaciated that he barely survived.

Although Yang was an excellent student, local Communist Party officials selected his older brother to be the first member of their family to attend college. Reasoning that the party was unlikely to select a second college student from the same family, he resigned himself to a life herding pigs.

But when the party reinstated the national college entrance exam, he took it and was among the 1% of applicants who were allowed to enter college. He graduated from Beijing Agricultural University in 1982, and after acing another exam was allowed to attend graduate school in the United States. He received his doctorate in embryology from Cornell University in 1990 and joined the staff there before moving to Connecticut in 1996.

In 2000, he used his growing celebrity and a recruiting offer from another university to convince Connecticut to establish a $20-million Center for Regenerative Biology and to hire five more specialists in the area.

In 1997, physicians diagnosed the salivary tumor. It was removed, but several recurrences made him progressively weaker, forcing him to take time off to recuperate. Although he largely stepped down in 2007, he continued to consult with his colleagues and serve as an advisor.

Yang, who lived in Storrs, Conn., is survived by his wife, Xiuchun “Cindy” Tian, an associate professor of animal science at Connecticut; a son, Andrew, who lives in Storrs; his parents, Wukui and Fengrong; three brothers, Huaizhong, Jizhong and Wenzhong; and a sister, Meiying.