Drought blocking passages to sea for California coho salmon

- Share via

DAVENPORT, Calif. — By now, water would typically be ripping down Scott Creek, and months ago it should have burst through a berm of sand to provide fish passage between freshwater and the ocean.

Instead, young coho salmon from this redwood and oak-shaded watershed near Santa Cruz last week were swirling around idly in a lagoon. There has been so little rain that sand has blocked the endangered fish from leaving for the ocean or swimming upstream to spawn.

Scott Creek is one of dozens of streams across California where parched conditions have put fish in immediate danger. With the drought, stream flows have been so low that even months into winter, sandbars have remained closed and waters so shallow that many salmon have had their migratory journeys obstructed.

To prevent further stress to salmon and steelhead, state wildlife officials have closed dozens of rivers and streams to fishing, including all coastal streams west of California 1. A storm that soaked parts of Northern California over the weekend should offer a short respite, but experts say streams like Scott Creek will need several inches of rain a week to stay open and connected to the ocean.

Nowhere is the situation more pressing than on California’s North and Central Coast, where a population of only a few thousand coho salmon were already teetering on the edge of extinction.

“This is the first animal that will feel the impacts of the drought,” said Jonathan Ambrose, a National Marine Fisheries Service biologist who stood at the sand-blocked mouth of Scott Creek to offer his assessment Wednesday. “It’s going to take a lot of rain to bust this thing open. And if they can’t get in by the end of February or March, they’re gone.”

Historically, hundreds of thousands of Central California Coast coho salmon started and ended their lives in creeks that flow from coastal mountains and redwood forests to the coast from Humboldt County to Santa Cruz.

Of those that remain, most at risk are coho salmon from about a dozen streams on the southern end of the species’ range in North America. If not for a small hatchery near the town of Davenport keeping the population going and genetically viable, coho salmon would probably already be long gone south of the Golden Gate.

The Central Coast population of coho has plummeted from about 56,000 in the 1960s to fewer than 500 returning adults in 2009. Over the last several years it has hovered around a few thousand, according to estimates from the National Marine Fisheries Service.

The population was listed as federally threatened in 1996 and reclassified as endangered in 2005. A 2012 federal plan estimated its recovery could take 50 to 100 years and cost about $1.5 billion.

“Coho are the fish that are really in trouble in the state right now,” said Stafford Lehr, chief of fisheries for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

“Right now, they’re cut off in many of the streams. They’re stuck in pools,” Lehr said. “As we move deeper into this drought, every life stage is going to suffer increased mortality.”

It’s not only Central Coast salmon that are in peril.

To the North, on Siskiyou County’s Scott River, more than 2,600 coho salmon returned this winter to spawn — the highest number since 2007 — but they encountered so little water they weren’t able to reach nine-tenths of tributaries to spawn, said Preston Harris, executive director of the Scott River Water Trust.

In the Sacramento River, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service plans to release more than 190,000 hatchery-reared chinook salmon Monday to take advantage of recent rainfall. Commercial fishing groups, however, are urging wildlife officials to consider trucking chinook downstream.

“We’re in such extremely low-flow conditions that they might as well dig a ditch and bury these fish rather than trying to put them in a river,” said Zeke Grader, executive director of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations.

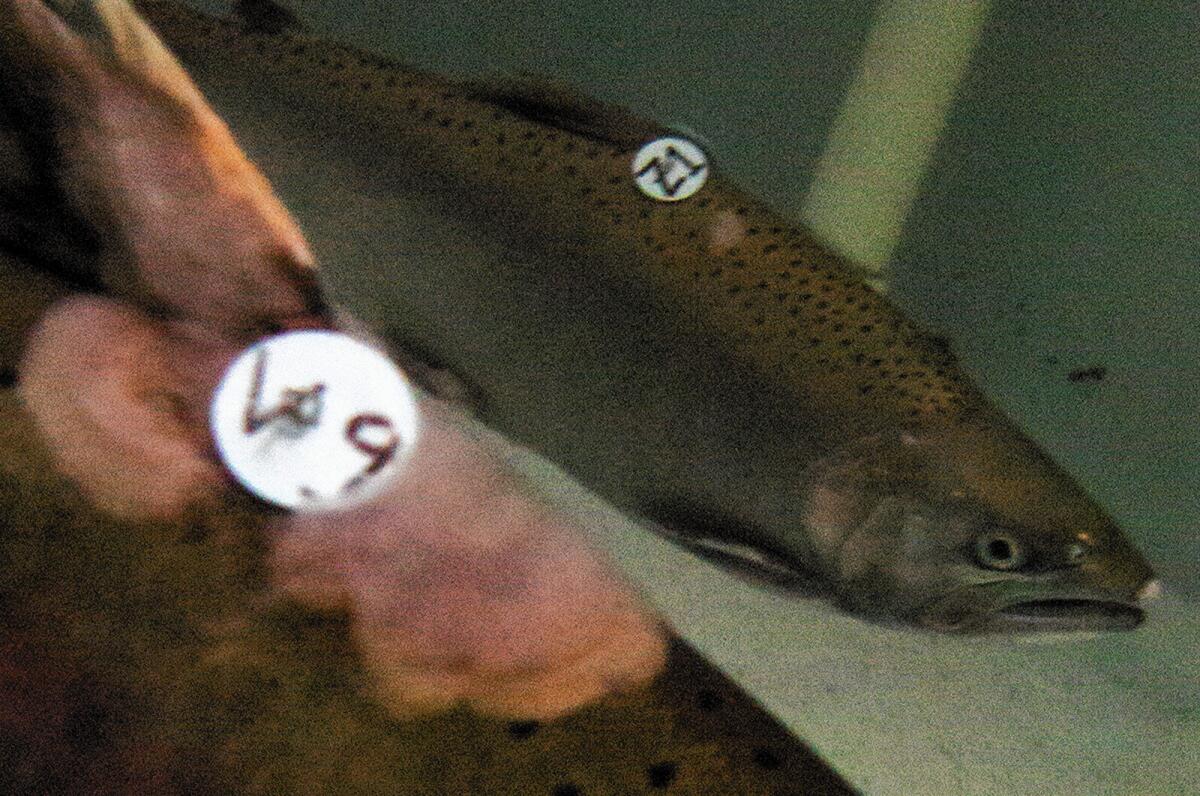

On the banks of Big Creek, a tributary of Scott Creek a few miles from the coast near Santa Cruz, some 41,000 coho salmon just over a year old are being raised to be released this spring at a conservation hatchery operated by the nonprofit Monterey Bay Salmon and Trout Project.

For now, hatchery managers can only wait and hope for rains heavy and consistent enough to swell the creek’s waters and give the fish a route to the sea. Barring that, wildlife officials overseeing the hatchery are considering drastic measures, such as bulldozing a channel through the berm of sand or releasing the young fish directly into the ocean.

Salmon have existed more than a million years and have evolved with California’s climate. Scientists say they have survived dry spells much worse than this one.

What has changed in recent generations is the pressure California’s growing population has exerted on the water supply and their habitat. Farms, vineyards and cities now divert stream flows while roads, logging and urban development have degraded water quality.

Coho salmon also have a rigid life cycle that makes them more vulnerable during droughts. After three years, they must return from the ocean to the stream where they were born to spawn and die.

That urge was all too apparent when scientists observed this winter’s returning Central California Coast coho salmon. Hundreds of the roughly 1,000 adults that arrived were schooling in estuaries, waiting for rain to provide them passage upstream.

“Many of these fish may simply die in the estuary without reproducing if they can’t access spawning grounds,” said Charlotte Ambrose, salmon and steelhead recovery coordinator at the National Marine Fisheries Service. “While some rain has come, for coho this year it may be too little too late.”