Out of fuel, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft ends its mission to study the asteroid belt

- Share via

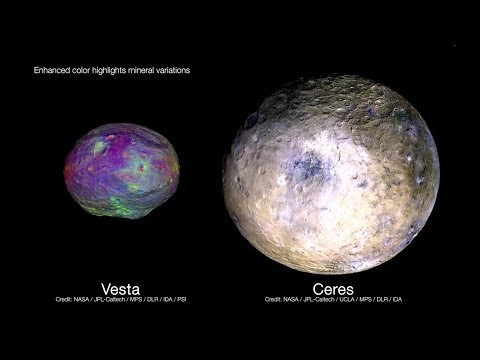

NASA’s Dawn mission to explore Vesta and Ceres, the two largest worlds in the solar system’s main asteroid belt, has come to a close.

The spacecraft has run out of hydrazine, the chemical fuel it needs to orient itself in the vacuum of space, NASA officials said Thursday.

That means it can no longer point its antennas toward Earth to send and receive data. Nor can it point its solar panels to the sun to recharge its batteries.

The spacecraft missed its scheduled communications sessions with NASA’s Deep Space Network on Wednesday and Thursday, confirming that it is no longer operational.

“We’ve known for months that it would most likely run out of fuel between the middle of September and the middle of October,” said Marc Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer and mission director at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. “To me, every time we communicated with it in the past two months has been one more bonus on an already fabulously productive mission.”

This is the second time this week that a NASA space mission has been terminated because of an empty fuel tank. On Tuesday, the space agency announced that its planet-hunting Kepler mission had also run out of fuel and was being decommissioned.

Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division in Washington, D.C., said the timing was pure coincidence.

“Both Kepler and Dawn have run out of fuel at exactly time they were expected to,” he said. “We’re not surprised.”

The Dawn mission launched in September of 2007, bound for the asteroid belt that lies between Mars and Jupiter.

Its goal was to study the two largest objects in this region and see what they could tell us about the birth of the solar system and the formation of its planets.

“In the broadest sense, we wanted to investigate the conditions and processes that existed at the earliest epoch of our solar system,” said Carol Raymond, a JPL scientist and principal investigator for the mission.

The spacecraft’s first stop was Vesta, a dry, lumpy asteroid about 325 miles in diameter. From July 2011 through September 2012, the spacecraft probed the chemistry of Vesta, discovering a complex geology that included an iron core, much like the one inside Earth.

Dawn also spotted a big splotch of water-rich minerals on Vesta’s surface that were likely deposited by asteroids or comets from the outer solar system.

“The same process has been invoked as an explanation for how Earth has so much water, so that is a really nice discovery to make,” Raymond said.

The spacecraft arrived at Ceres in March 2015 and quickly revealed an unexpectedly dynamic world shaped by recent volcanoes and seasonal ice cycles. Dawn revealed that the 588-mile-wide dwarf planet was born in the outer solar system and migrated to its current location long ago.

The chemistry of its crust suggests that Ceres once harbored a global liquid ocean beneath its surface. That global ocean is no more, but Dawn’s observations indicate there could be some remaining pockets of briny liquid.

The spacecraft also discovered organic material — the building blocks of life — on Ceres’ surface.

“We’re not saying they are indicative of life or evidence of life, but it does make Ceres a more interesting object from the habitability perspective,” Raymond said. “The bottom line is we now know enough about Ceres to know it would be a fantastic target for in depth exploration.”

After a careful analysis, Dawn’s engineering team determined that they didn’t need to do anything special to the spacecraft before declaring it officially decommissioned.

Its transmitter would automatically shut off once the fuel ran out, and it was already in a safe, stable orbit around Ceres.

Although Dawn is now dead, Raymond hopes that one day another spacecraft will return to the dwarf planet.

“There is so much more we want to learn,” she said. “We didn’t go and find this inert object with a record of stuff that used to happen. It was almost like, ‘It’s alive.’”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE