In the DNA of an ancient infant, scientists find traces of the very first Americans

- Share via

Across a span of 11,500 years, a baby is speaking to us.

Although she was just an infant when she died, her diminutive remains are helping researchers understand how ancient people first entered and then moved around the Americas.

The little girl recently was given the name Xach’itee’aaneh T’eede Gaay (Sunrise Girl-Child) by indigenous people in the Alaskan interior who live close to the place where her body was found.

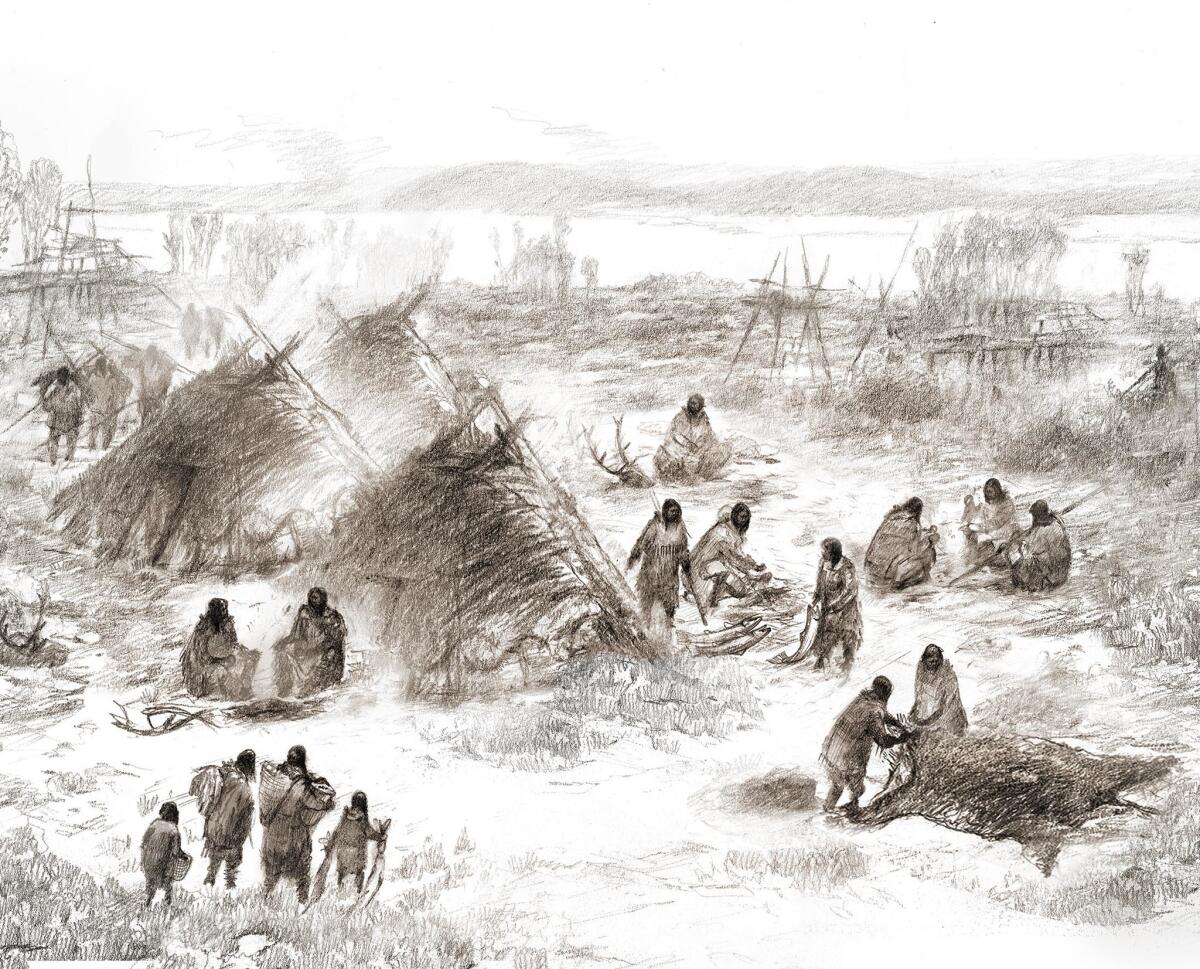

Archaeological evidence suggests her family buried her with care in a pit beneath the central hearth in their temporary home. They laid her to rest on a bed of ocher and placed offerings of weapons around her makeshift grave.

Centuries later, her tiny skeleton was unearthed during an archaeological dig, and, with the permission of local indigenous tribes, samples of her bones were sent off for DNA analysis.

Scientists were stunned by what they revealed: This little girl was born into a previously unknown population of pioneers who were among the first to arrive in North America.

The discovery, reported Wednesday in Nature, has both complicated the story of how humans spread throughout the Americas and brought it into clearer focus, said Ben Potter, an anthropologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks who worked on the new study.

“No one can deny that this makes our picture of the history of Native Americans more complex and more accurate than ever before,” he said.

David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, hailed the new work as a crucial step toward better understanding how the earliest migrants to the New World diversified once they got here.

“This is an important finding, as it constrains possible scenarios for the early peopling of the Americas in significant ways,” he said.

The baby’s grave was discovered in 2013 in an archaeological site known as Upward Sun River in Alaska’s Tanana River Valley. It appears to have been a residential base camp where men, women and children remained for several weeks at a time, primarily in the summer months. The site was occupied multiple times, beginning about 13,000 years ago.

The remains of Xach’itee’aaneh T’eede Gaay date back to about 11,500 years ago. She was buried along with another female infant who appears to be a close relative, but not a sister, the researchers said. Genetic analysis shows that the two had different mothers.

It’s never easy to get usable DNA from ancient bones. But with Sunrise Girl-Child, the research team got lucky. Her DNA was well-preserved in deep sediments, which made it easier for modern scientists to decode it.

Things didn’t go as well for the second infant. The research team was able to analyze enough of her nuclear DNA to confirm that the two girls were related. However, a previous study found that their mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited only from one’s mother, was different.

Next the authors compared the more complete genetic sequence from Sunrise Girl-Child with that of other ancient genomes, as well as a panel of DNA profiles from 167 populations around the world. The baby’s DNA was more closely related to present-day Native Americans than to any other tested populations, followed by Siberians and East Asians.

That didn’t come as much of a surprise. There is broad agreement among anthropologists and archaeologists that the first people who came to America traveled over Beringia, a strip of land that connected northeast Asia with northwestern North America during the last ice age, when sea levels were lower.

The part that was shocking was the discovery that the baby girl was equally related to both groups of present-day Native Americans — those who live in northern North America, including Athabaskan and Algonkian speakers, and those who live farther south.

For this to be true, she must have belonged to a third group of people who lived before the northern and southern Native Americans split into genetically distinct groups, the researchers said. They dubbed the newly identified group the Ancient Beringians.

“This was brand-new,” Potter said. Scientists “simply didn’t have this population on the radar.”

Further genetic analysis suggested that the Ancient Beringians split from the ancestors of all other Native Americans about 20,000 years ago, well before Sunrise Girl-Child was born. It is likely that the Ancient Beringians stayed in the north, while the ancestors of all other Native Americans moved south before splitting into two other groups around 15,000 years ago.

Potter said it is still unclear what ultimately happened to the Ancient Beringians. Perhaps they were absorbed by other Native Americans who moved back into their region about 6,000 years ago and intermarried. It is also possible they were killed off or out-competed by their neighbors to the south.

“We are still at a very early stage of understanding,” he said. “The simple answer is we don’t know.”

However, the story of how people came to the Americas in the first place is becoming clearer.

Thanks to the additional genetic data provided by Xach’itee’aaneh T’eede Gaay, the authors say they have the first evidence of a single founding Native American population, which split from East Asians about 35,000 years ago.

“Finding a single individual that connects both north and south Native Americans genetically is a significant finding because it gives evidence of a single early migration,” said John Lindo, an anthropologist at Emory University in Atlanta who was not involved in the work.

He added that the study also gives credence to an earlier theory: that the original migrants to the New World stayed in Beringia long enough to become genetically distinct from people in East Asia.

But Potter said it is still up for debate whether a single group crossed the Beringian land bridge and split afterward, or if the groups already were distinct before coming to the Americas.

“We have too little data to firmly reject any of the major ideas for the route that people took into the New World,” he said.

He said future discoveries of ancient remains could help answer some of these questions, but those findings tend to be few and far between.

In the meantime, the DNA evidence embedded in Xach’itee’aaneh T’eede Gaay’s small bones will enable researchers to craft better hypotheses about how people first came to the Americas that can be tested in other ways — such as archaeology and paleoecology.

“The awesomeness of this study is that it gives us a new line of questions to explore,” Potter said.

MORE IN SCIENCE

11 science stories we’re looking forward to in 2018

Do psychiatrists have any business talking about President Trump's mental health?

Autism spectrum disorders appear to have stabilized among U.S. kids and teens