NASA’s New Horizons to make history with far-out visit to Ultima Thule

- Share via

In the cold vacuum of space, 1 billion miles past Pluto, a piano-sized spacecraft is about to make history.

NASA’s New Horizons probe is scheduled to fly past a mysterious object known as Ultima Thule at 9:33 p.m. PST on New Year’s Eve.

Located roughly 4 billion miles from Earth, it will be the most distant world ever visited by humankind.

And because it has probably remained in a deep freeze for 4.5 billion years, Ultima Thule could be the most pristine example of the solar system’s original disk of dust and gas ever observed.

“We’ve never seen anything like this and we don’t quite know what to expect,” said Alan Stern, the principal investigator for the mission. “We’re going to go from a dot in the distance on New Year’s Eve to maps on Jan. 2.”

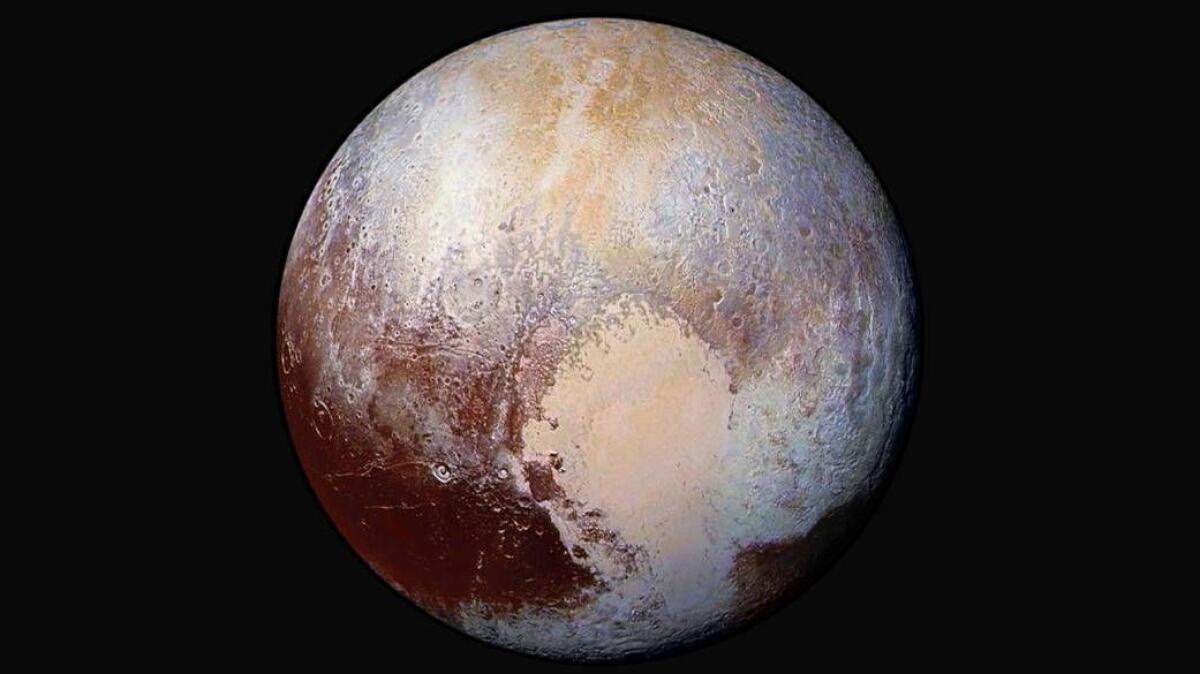

You may remember New Horizons as the spacecraft that gave humanity its first close-up view of Pluto in 2015.

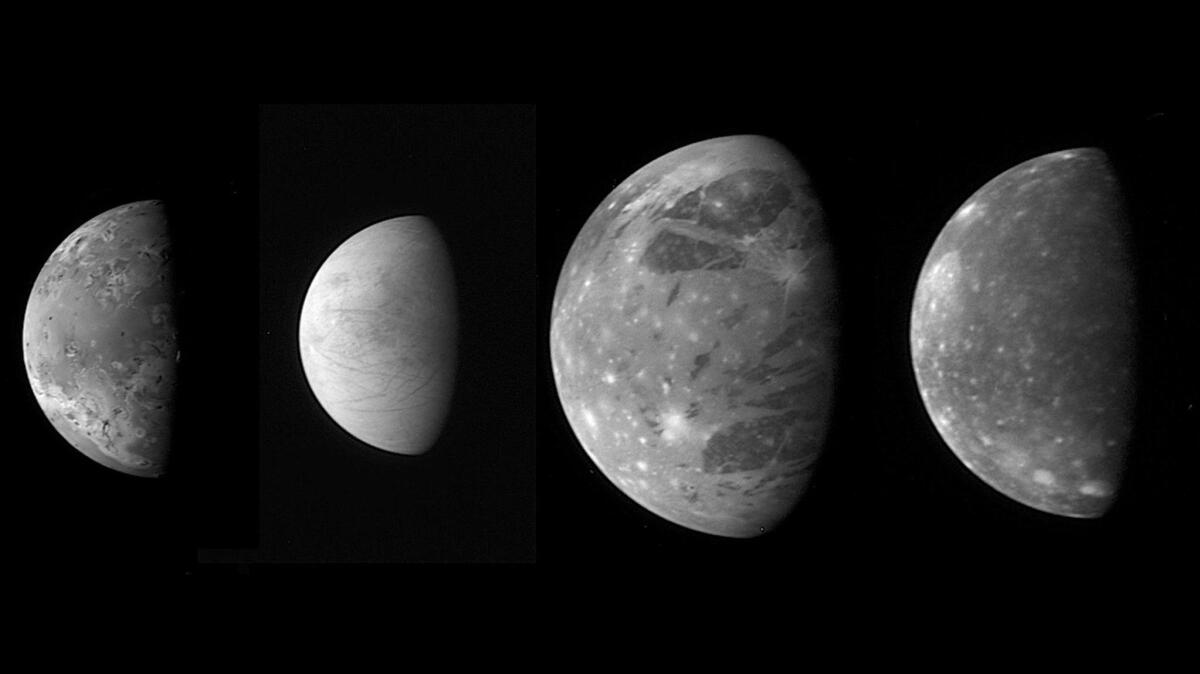

The high-definition images it sent back shocked scientists, revealing an unexpectedly active world with towering mountains, steep cliffs and glaciers of frozen nitrogen. The probe also created temperature maps of Pluto’s multicolored surface, looked for auroras in its thin atmosphere and measured the dust and plasma in its environment.

NASA’s New Horizons probe will take even more detailed images of Ultima Thule than it did of Pluto in 2015.

Ultima Thule is 100 times smaller than Pluto, but New Horizons will get three times closer to its surface than it did to the dwarf planet, observing it from just 2,200 miles away at its closest approach.

On Pluto, the space probe was able to see individual features the size of Central Park in New York City.

On Utlima Thule, the resolution will be even better.

“We’ll get down to about the size of two baseball diamonds,” said Stern, who is based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

The first images from this faraway frozen world will reach Earth on New Year’s Day. Mission planners expect to release them to the public on Jan. 2.

“This is really terra incognita,” said New Horizons project scientist Hal Weaver, who works at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. “It’s the frontier of planetary science.”

New Horizons blasted off from Earth way back in January of 2006. It traversed 3 billion miles of space — visiting Jupiter and observing its rings and moons along the way — before making its closest approach to Pluto 9½ years later.

“It’s been a mission of delayed gratification,” Stern said.

Pluto was New Horizons’ first and primary destination, but the spacecraft still had half a tank of propellant after that encounter, and its instruments all had a clean bill of health.

In 2016, NASA gave mission planners the go-ahead to explore additional objects in the Kuiper Belt — a cold, doughnut-shaped region of the outer solar system that includes Pluto and hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of other worlds.

“I call Pluto the gatekeeper of the Kuiper Belt,” Weaver said. “It’s the biggest and brightest object we can see, and it’s right on the inner edge.”

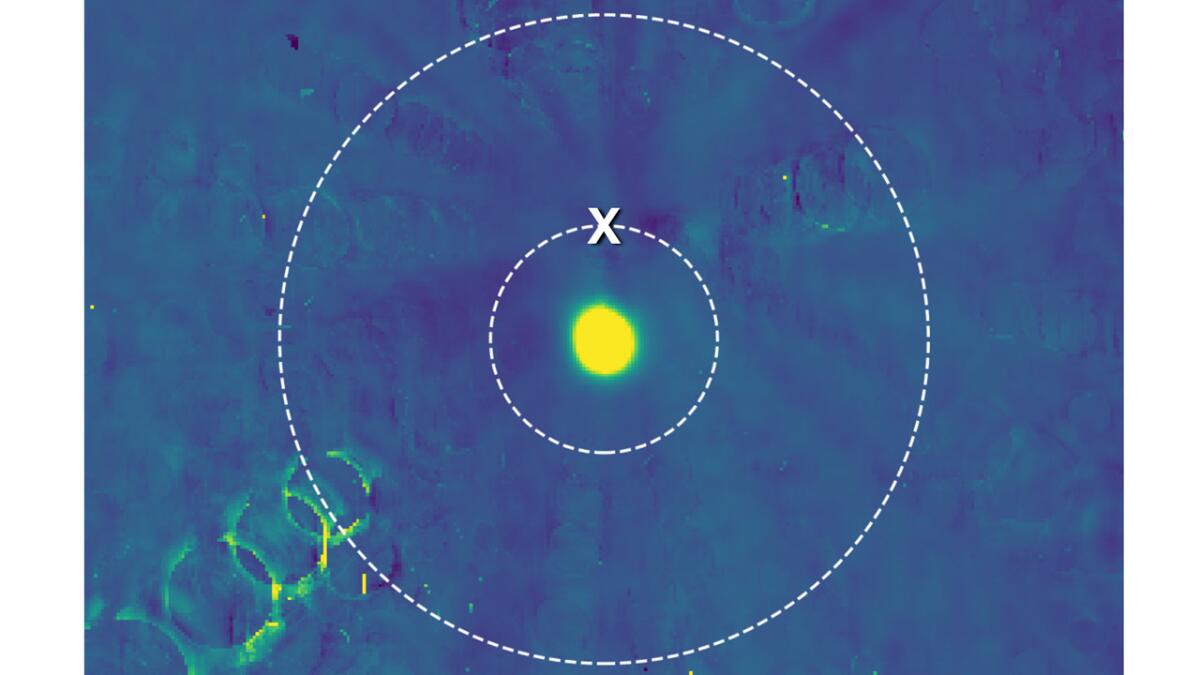

Ultima Thule lies in the center, and most dense region, of the Kuiper Belt, Weaver said. Discovered in 2014, it is so far from Earth and so dim that even to the Hubble Space Telescope it appears as little more than a point of light moving against the stars.

To characterize it, astronomers used a technique known as stellar occultation. By watching Ultima Thule pass in front of a star and measuring how long the star is hidden from sight, they are able to ascertain that it is about 20 miles long and almost certainly not spherical.

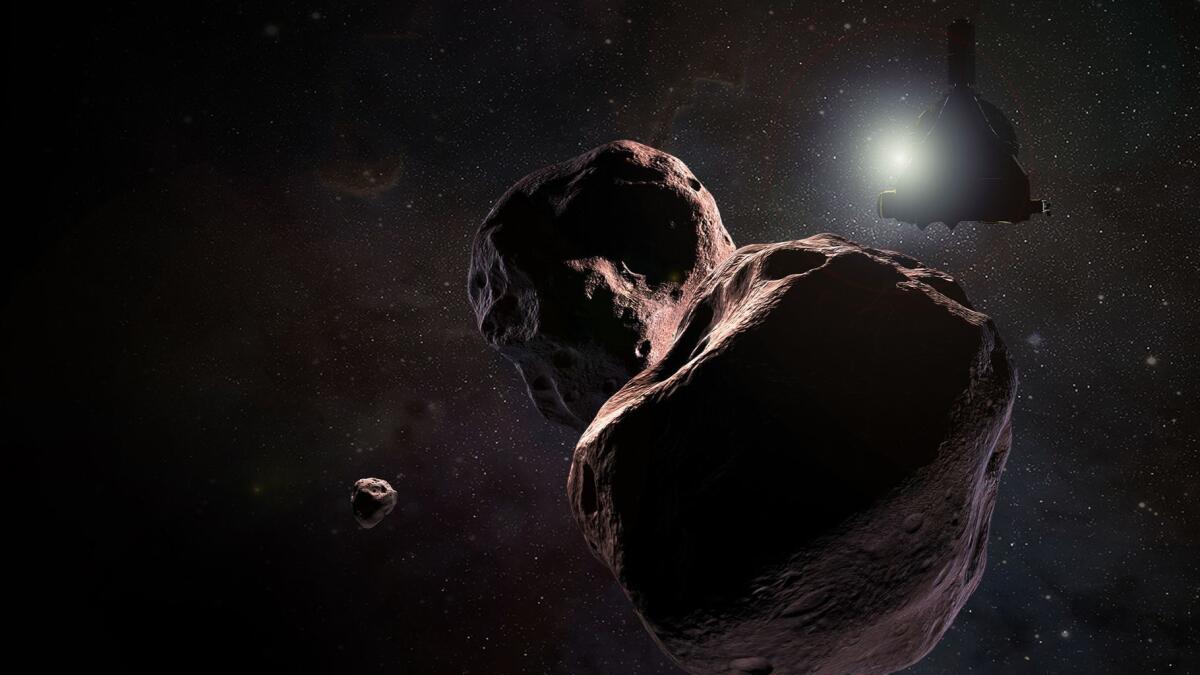

It might be shaped like a lumpy potato, said astronomer Marc Buie, a colleague of Stern’s at the Southwest Research Institute who led the occultation work. Or it might be shaped like a headless snowman — two balls stuck together, he said.

Its surface is probably reddish in color and reflects just 10% of the light it receives. That makes it significantly darker than any of the surfaces on Pluto, and about as bright as the surface of our moon.

“That tells us a bit, but only a bit,” Buie said. “We’ll know a lot more on Jan. 1”

The New Horizons team has given their small spacecraft several science tasks to complete as it zips past Ultima Thule.

Chief among them is the search for any evidence that this small, cold world is not completely dormant.

“We know from measuring comets that they have lots of exotic ices that can go straight from the solid phase to the gas phase even in these incredibly cold temperatures,” Weaver said.

Volatile ices on the surface of Ultima Thule would have sublimated away long ago, but it is possible that similar compounds buried deep in the object’s interior could cause dust or gas to rise from its body and shoot off into space.

New Horizons will also use its infrared spectral imager to determine what minerals Ultima Thule might contain, how much water is locked away in its chemistry, and whether organic material exists on its surface.

Another instrument will examine dust scattered in the sunlight to see what molecules are floating in Ultima Thule’s vicinity. The spacecraft will also look at charged particles around the small world to see if it has any impact on the solar wind streaming past it.

“We are using every tool in our arsenal to pull down as much information as we can,” Weaver said.

New Horizons’ New Year’s Eve flyby will be more difficult than the one it made past Pluto a few years ago, said Chris Hersman, the mission’s chief engineer at Johns Hopkins.

Pluto is a larger object, and the point of closest approach was further away. Therefore, New Horizons’ instruments had more time to collect data than they’ll have with Ultima Thule, Hersman said.

“Think of an old airplane barnstorming a field,” he said. “The closer you get to the ground, the harder it is to take a picture of something in the field. The further away you are, the more time you have to take the picture.”

When New Horizons flew past Pluto, it had about 48 hours to collect its best data. When it flies past Ultima Thule, it will have less than five hours to take similar measurements, Hersman said.

In addition, the team practiced its Pluto flyby by putting the spacecraft through its paces around an imaginary object while it was en route. The operations team didn’t have time to do that on the way to Ultima Thule, and they were also concerned about wasting fuel, Hersman said.

New Horizons will also be operating with less electrical power than it had at Pluto. That’s because the spacecraft’s power is produced by the decay of radioactive material. Over time that decay results in less and less heat, which translates into less power.

“You do the best you can with the resources you have,” Hersman said. “But I’m confident that we have put together the best chance for a successful flyby.”

Even if everything goes as planned on New Year’s Eve, the New Horizons team won’t be entirely out of the woods. Hersman said his team is still working out how to retrieve all the data from the spacecraft as quickly as possible.

“The longer it sits on board, the more risk that something could happen to it,” he said.

And there is the lingering question of where to send the spacecraft next. When the flyby is over, New Horizons will still have a quarter of a tank of propellant left.

“We’ve got the capability for another flyby and enough fuel in the tank to go for another 20 years,” Stern said. “The plan is to run it down doing science.”

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE