Scientist who created STAP stem cells says studies should be withdrawn

- Share via

A number of scientists have been grumbling for weeks about a pair of breakthrough stem cell studies that seemed too good to be true. Now one of the senior researchers who worked on the papers agrees that they may be right.

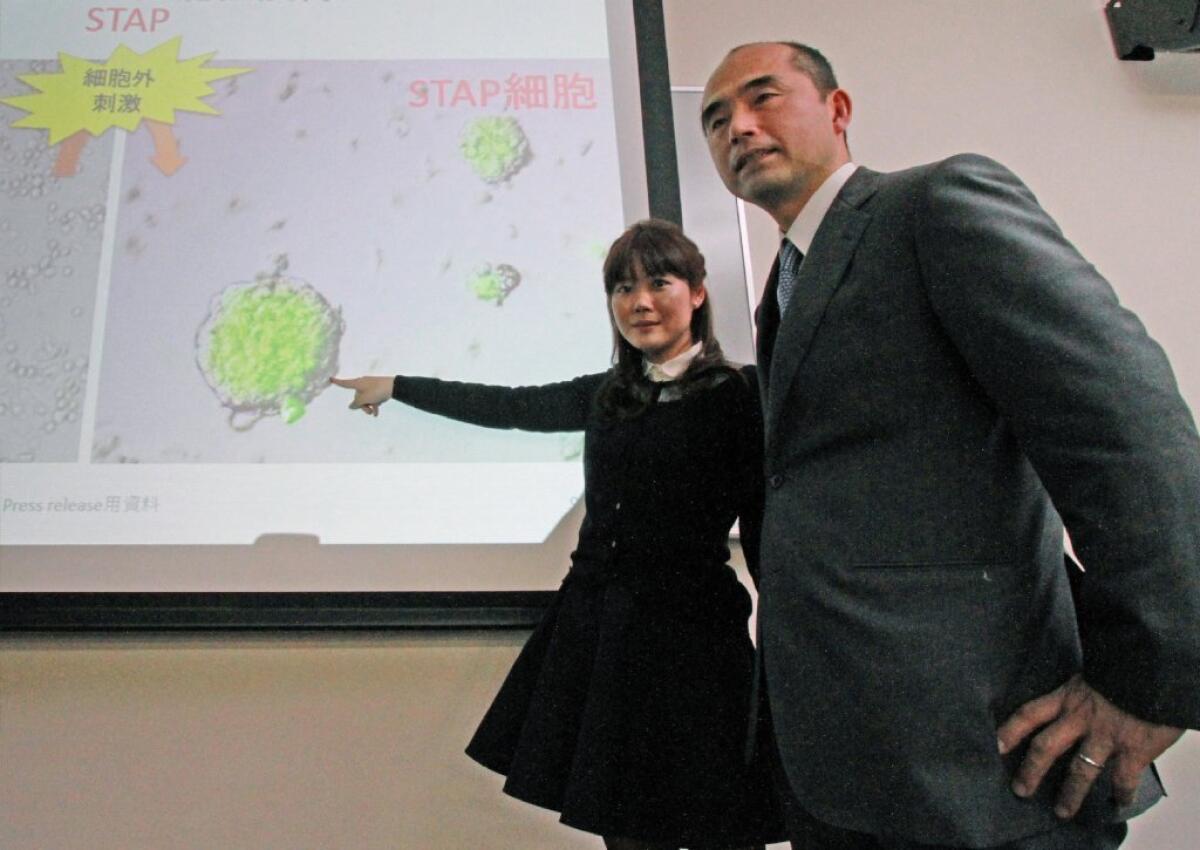

The studies, which were published in January by the journal Nature, described a surprisingly simple method of transforming mature cells into pluripotent stem cells capable of regenerating any type of tissue in the body. The key was to stress them out by soaking them in an acid bath for 30 minutes, prompting genetic changes that made the cells more flexible. The researchers dubbed their technique “stimulus triggered acquisition of pluripotency,” or STAP.

But Teruhiko Wakayama, a senior author of one of the papers and coauthor on the other, said he had lost confidence in the studies and was “no longer sure the STAP cells were actually created,” according to NHK.

Wakayama, a professor at the University of Yamanashi in Kofu, Japan, told Japanese media Monday that he had asked his collaborators to withdraw the studies until the results could be verified by independent scientists. He added that “he is ready to provide cell samples and detailed data” to anyone who is willing to try, NHK reported.

RELATED: New method makes stem cells in about 30 minutes, scientists report

Wakayama also echoed concerns raised by others that some of the images used in the Nature papers may have been published previously. According to Japan News, an English-language website from Yomiuri Shimbun, Wakayama said the images “look almost identical” to images that appear in the PhD thesis of Haruko Obokata, the lead author of both Nature studies. Her thesis was about pluripotent stem cells in humans, but the cells in the Nature STAP paper were supposedly from mice.

Anonymous posters to a website called PubPeer have flagged several images in the Nature papers that they say look suspiciously like pictures in a 2011 study led by Obokata. That study, published in the journal Tissue Engineering, purports to show that cells removed from various tissues of adult mice could be coaxed to grow into other kinds of cells.

Duplicated images aren’t the only problem skeptics have flagged. A Japanese blog post has noted striking similarities in the words used to describe some of the methods used in one of the Nature papers and the words in a 2005 paper published in a journal called In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology – Animal. In the blog post, the overlapping language is highlighted in red.

“There sure seems to be a lot of overlap in text in the two papers,” Paul Knoepfler, a stem cell researcher at UC Davis, wrote on his blog.

“I’ve heard people react to this by saying ‘no big deal, it’s just a methods section,’ while I’ve heard others say ‘this is misconduct,’” Knoepfler added. “I’m sure many people fall somewhere in the middle.”

Knoepfler has been blogging about the STAP research since the day the studies were published on Nature’s website nearly six weeks ago. Right away, something about them seemed odd.

“After a relatively quick read, no particular red flags jump out at me from the STAP cell paper,” he wrote on his blog. “It just seems too good and too simple of a method to be true, but the data would suggest so far at least that this team is onto something really important.”

As the days and weeks passed, Knoepfler’s suspicions grew. He has posted polls asking readers to weigh in on whether they think STAP cells are “real.” (At the moment, only 17% are pretty convinced that they are real, while 52% are pretty convinced that they are not.) He has also asked fellow researchers who are trying to make STAP cells in their own labs to share their results. So far, none have succeeded.

These concerns and others prompted the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, where Obokata works, to launch an investigation into the matter in mid-February. That inquiry is still ongoing, with the research institution considering whether to withdraw the STAP studies, Japan News reported Tuesday. More details are expected Friday.

Nature, the London-based journal that published the STAP papers, also began investigating the studies around the same time. The journal has declined to elaborate until its review is complete.

In the meantime, Obokata and two of her RIKEN colleagues published a more detailed explanation of their research methods on Nature’s Protocol Exchange website to address some of the questions that have been raised.

In late February, Wakayama told Knoepfler he was not surprised that other research groups hadn’t been able to make STAP stem cells yet. (Even he’s had trouble reproducing the study results since he left RIKEN and set up his new lab at the University of Yamanashi.)

“It is going to take time to reproduce the new technique,” Wakayama said in a Q&A posted on Knoepfler’s blog. “For example, the first cloned animal, Dolly, wasn’t reproduced for one and half years after it was published. Human cloned ES cell paper [published in May 2013] has still not yet been reproduced. Therefore, please wait at least one year. I believe that during this period someone or myself will success to reproduce it.”

That optimism may be gone now. At Monday’s news conference, Japan News quoted Wakayama as saying, “I’m no longer sure that the articles are correct.”

Obokata, who became a national celebrity in Japan after the papers were published, has not addressed the controversy. But one of her coauthors, Dr. Charles Vacanti of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, told the Boston Globe he still believes the STAP findings are sound.

“I think there were some simple, perhaps sloppy mistakes that I thought were honest mistakes,” said Vacanti, whose name is on both Nature papers and was also the senior author of the 2011 report in Tissue Engineering. “I don’t have any information that would make me change my opinion of what I said before.”

Harvard Medical School is looking into the matter as well, according to Japan News.

If you’re interested in the latest scientific and medical studies, you like the things I write about. Follow me on Twitter and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.