Underwater microscope catches corals dancing in their natural habitat

- Share via

A new underwater microscope allows scientists to take their lab right to the bottom of the ocean, where they can get up close and personal with coral and other sea life to see how they behave in their own watery domain.

This high-powered tool, described in a paper published Tuesday in Nature Communications, is already revealing new details about life at the sea floor and the inner workings of mysterious marine organisms like coral.

Coral reefs can stretch for miles. The huge structures are built by tiny animals, called polyps, that are related to jellyfish and sea anemones. It takes millions of them to build and maintain a reef.

See the most-read stories in Science this hour »

“We want to look at those 1-millimeter-sized guys and see what their lives are like,” said study lead author Andrew Mullen, a graduate student in ocean engineering at UC San Diego.

The underwater microscope consists of a camera that can record photos and video, along with a computer that focuses the lens and stores images. They are housed in separate aluminum cylinders that can be safely submerged. The microscope unit is attached to a tripod that lets the scientists set it exactly where they want it.

A ring of white LED bulbs provides the illumination required to snap brilliant images to a resolution of nearly one micrometer, or about one-hundredth of the width of a human hair. The scientist in control of the unit can see each image as it’s taken, providing live feedback on the quality of each shot.

Mullen and his colleagues used the new contraption to observe stretches of coral reefs off the coast of Maui and the Israeli city of Eilat. In both places, they dived to the ocean floor and selected a small section of reef to examine. After positioning the microscope lens about 2 inches above the coral — much farther away than conventional microscopes — and tweaking a few settings on the computer, the structure of the polyps was brought sharply into focus.

Coral polyps resemble upside-down jellyfish attached to rocks. Each one has a ring of tentacles around a sac that acts as the animal’s stomach.

Two polyps of a Stylophora coral eat brine shrimp in this time-series video filmed in a lab. (Jaffe Lab for Underwater Imaging, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego)

The new microscope allowed scientists to look within the translucent coral skeleton and see the microscopic plant cells living inside. These tiny algae provide nutrients to the coral — allowing the colony to grow about an inch each year — and give a reef its unique and vibrant color.

To the naked eye, coral appear to lead relatively calm and still lives. But they do move around quite regularly, and the cutting-edge instrument offered scientists a peek into the delicate and methodical movements of the minuscule creatures.

With the microscope watching, the polyps’ tentacles gently swayed back and forth to pull in plankton and other microscopic organisms that floated by. The device captured some never-before-seen images of coral polyps “kissing” after eating, which researchers think could be a way of sharing nutrients across a coral colony.

Polyps on a Stylophora coral are seen “kissing” in the wild. (Jaffe Lab for Underwater Imaging, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego)

When the researchers left the microscope on overnight, they captured a series of images that showed the slight dancing and waving movements that polyps make.

In a short time, the microscope has already unmasked valuable information on some of the complexities of coral life, such as the competition for territory on the sea floor.

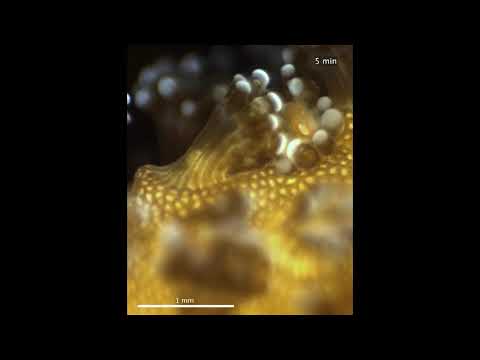

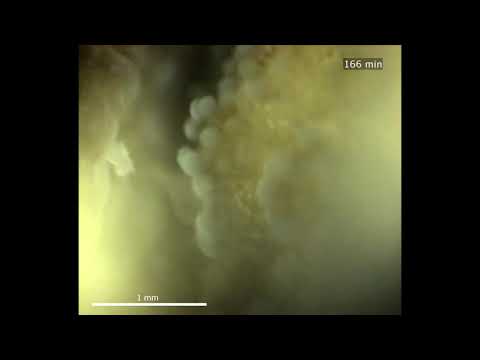

When the researchers set two competing species of coral near each other, they observed the stronger one sending out filaments — thin, worm-like fingers that act as its gut — and coating the tissue of the weaker one.

“They use those filaments to basically digest the neighbor next to them,” Mullen said.

Removing neighboring competition is no small feat — consuming a nickel-sized chunk of its opponent took nearly an entire night.

Corals Stylophora , left, and Pocillopora, right, compete with each other, filmed in the wild. A fragment of the Stylophora found nearby was moved closer to the Pocillopora to induce competition. (Jaffe Lab for Underwater Imaging, Scripps Insti

Mullen said the best thing about the microscope is that it allows scientists to conduct their research without disturbing their subjects.

“If you take coral and bring it back to the lab, you can precisely study it, but you’re totally removing it from its natural conditions,” Mullen said.

Those conditions, including the temperature and acidity of the water and the activity of nearby ocean organisms, can have a big influence on coral behavior.

Most of the factors that either make coral polyps healthy or lead to their deterioration can only be studied in the wild, said Victor Smetacek, a professor of bio-oceanography at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany who was not involved with this study.

“It’s like studying an ant in a cage and drawing conclusions about what it does in nature,” Smetacek said. “These details of their day-to-day life can only be revealed by direct observation.”

So far, this new microscope has only been used to image coral, but it could delve into the secret lives of other marine creatures, such as kelp forests or seagrass beds.

“These videos are examples of what it can do now,” Mullen said. “And they’re a little bit of a taste of what we can do in the future.”

Follow @mdaley_ on Twitter for more science news and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE IN SCIENCE

‘Pokemon Go’ players are finding real animals while searching for digital ones

Science proves it: Girl Scouts really do make the world a better place