What do you get when you combine a hurricane and an earthquake? A ‘stormquake’

- Share via

Scientists have discovered a mash-up of two disasters — hurricanes and earthquakes — and they’re calling it a “stormquake.”

The shaking of the seafloor during hurricanes and nor’easters can rumble like a magnitude 3.5 earthquake and can last for days, according to a study published this week in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. The quakes are fairly common, but they weren’t noticed before because they were considered seismic background noise.

A stormquake is more an oddity than something dangerous, because no one is standing on the seafloor during a hurricane, said Wenyuan Fan, the Florida State University seismologist who led the study.

The combination of two frightening natural phenomena might bring to mind “Sharknado,” but stormquakes are different in two important ways: They are real, and they are not dangerous.

“This is the last thing you need to worry about,” Fan said.

Big storms trigger giant waves in the sea, which in turn cause another type of wave. These secondary waves then interact with the seafloor — but only in certain places — and that causes the shaking, Fan explained. It only happens in places where there’s a large continental shelf and a shallow, flat seafloor.

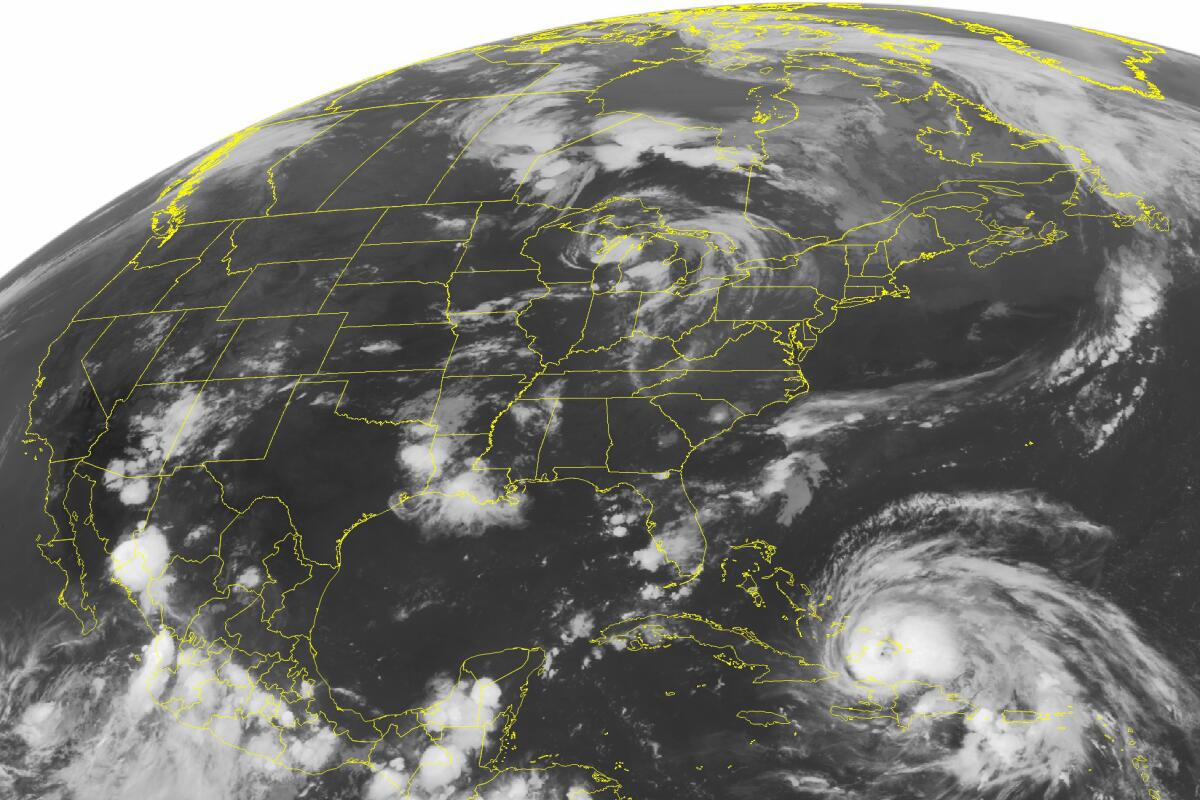

The research team detected 14,077 stormquakes between September 2006 and February 2015 in the Gulf of Mexico and off the coasts of Florida, New England, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, Labrador and British Columbia. A special type of military sensor is needed to detect them, Fan said.

Hurricane Ike in 2008 and Hurricane Irene in 2011 set off lots of stormquakes, according to the study.

The shaking is a type that creates a wave that seismologists don’t normally look for when monitoring earthquakes. That explains why they’ve gone unnoticed until now, Fan said.

Ocean-generated seismic waves show up on U.S. Geological Survey instruments, “but in our mission of looking for earthquakes these waves are considered background noise,” said seismologist Paul Earle of the USGS National Earthquake Information Center in Golden, Colo.

The study makes sense, said Lucia Gualtieri, a seismologist at Stanford University who wasn’t involved in the work. It’s interesting, she added, because it looks at a frequency of waves that scientists hadn’t examined much.