Nova Scotia may be best known as home of the Bay of Fundy. But there’s much more to Nova Scotia than watching the world’s highest tides roll in and out. With its rich colonial history, its ties to the sea and its natural rugged beauty, Canada’s eastern province is a land of quirky surprises, as I found on a recent visit. Here are a dozen that surprised me.

Paul Whitefield

Like a French Brigadoon appearing out of the mist, the Fortress of Louisbourg takes you back to a forgotten time and place. Take care, though: You may be accosted, in French, by guards demanding your papers before visiting the rooms where the governor once held court. Settled in 1713, Louisbourg, on Cape Breton Island -- or, to the French, Ile Royale -- was attacked and seized twice by the British, who finally destroyed it in the 1760s. Like the Citadel in Halifax, it fell into disrepair but was resurrected and now looks much as it did in 1744. Friendly, gregarious reenactors give you a taste of what life was like not only for the soldiers but the townspeople (think women with lots of children and men scraping out a living soldiering or fishing). Interesting tidbits include the tale of a black slave women who gained her freedom, and the fact that there was no church because the good folk of Louisbourg refused to tax themselves to pay for one. Now that’s separation of church and state! (Paul Whitefield / Los Angeles Times)

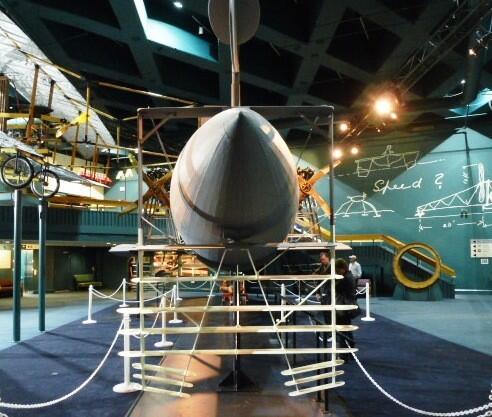

Sure, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. But at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site in the village of Baddeck on Cape Breton Island, you’ll learn all you don’t know about the famous American (actually a Scottish immigrant who liked to spend his summers in Canada). For example, he played a major role in the birth of aviation in Canada, helping design and build the Silver Dart, which made the first powered flight in Canada and the British empire on Feb. 23, 1909. He designed and built hydrofoil boats that set world speed records in the early 1900s. And he designed and built tetrahedral kites that could carry men aloft. All while helping hearing impaired people, raising a family, and studying nature, and -- well, go and you’ll find out for yourself. (Paul Whitefield / Los Angeles Times)

For many people, the big draw is its collection of Titanic artifacts. But c’mon, let your Titanic heart go on. For male kids of all ages, the best part just might be the collection of ship models. (The fake pirate hung in the lobby is ghoulish but fun too.) Great liners of the past, famous ferry boats and other vessels are rendered in exacting and astonishing detail. If you ever tried -- and failed -- to build a model ship, take a minute to wander through this exhibit and see how the pros do it. The museum also has a section on the Great Halifax Explosion of 1917, in which an ammunition ship was rammed by a cargo vessel in the harbor, caught fire and blew up, leveling a wide swath of the city and killing more than 1,900 people. Bet you didn’t know it was the largest man-made explosion before the nuclear bomb. If none of that floats your boat, you can always chat with the talking bird near the entrance, or watch him get his daily bath. (Paul Whitefield / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

When the White Star liner Titanic proved not so unsinkable in 1912, several ships from Halifax were chartered to recover bodies. Victims were interred at three cemeteries in Halifax, but the best known is Fairview Lawn Cemetery, where more than 100 souls were buried. Here you’ll find the marker for one “J. Dawson,” which fans of the movie “Titanic” wrongly assume is the inspiration for the Leonardo DiCaprio character. Also here is the marker to the “Uknown Child” (since identified) and to heroic Titanic steward Ernest Edward Samuel, who went down with the ship -- unlike the man who paid for his headstone, J. Bruce Ismay, chairman of White Star Lines, who found room on a lifeboat and survived. Rank has its privileges indeed. (Paul Whitefield / Los Angeles Times)