Venus chasers of the 18th century

- Share via

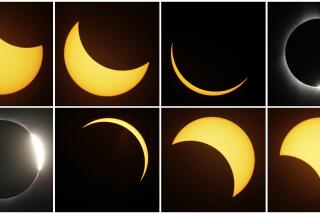

Forget the “ring of fire” solar eclipse. On Tuesday, the heavens have something much more exciting in store: a transit of Venus, which is one of the rarest of astronomical events. In the afternoon, just after

3 p.m. in California, Venus will move between Earth and the sun, and for a few hours it will be a perfect black dot moving slowly across the sun’s burning face.

Such transits come as pairs — with an eight-year interval — but it then takes more than a century for the planets to do the dance again. The transit of Venus this week will be the last until 2117. It represents not only a magnificent celestial encounter but a reminder of how science is a team sport. In 1761 and 1769, the effort to mark and measure the transit revolutionized science when it became the first-ever truly global scientific project.

It goes without saying that modern scientists connect with each other. They email, video conference, Skype, download, upload or tweet. They have access to digital resources that range from 18th century newspapers to reports on each other’s latest research on climate change. And easy and cheap travel, multinational funding and the Digital Age allow them to work together across long distances and national boundaries.

Two hundred and fifty years ago, it was not so simple a task. And yet, in 1761 and 1769, hundreds of astronomers from more than a dozen nations stationed at more than 130 locations around the world turned their telescopes simultaneously to the sky to observe the transit of Venus. They did so — at great peril and against heavy odds in many cases — because they believed that the transit held the key to one of the most pressing quests of the age: the distance between Earth and the sun and, by extension, the size of the solar system.

By establishing the time and duration of the transits, they hoped to work out the elusive question of distance. But there was one problem: Astronomers had to view the transit from as many places, as far apart as possible, around the globe. Depending on their position in the Northern or Southern hemispheres, they would see Venus crossing the sun on a slightly different track. With the help of relatively simple trigonometry, these different tracks would allow them to arrive at a measurement. They had to travel to the outposts of the known world, and no single national effort would be able to make this happen.

Nations at war had to collaborate. Much of Europe as well as North America, the Caribbean and India were involved in the Seven Years War, but scientific societies in London, Paris, Stockholm and other cities coordinated dozens of intrepid astronomers who crossed national and colonial borders to get to Tahiti, the Arctic Circle, Siberia, India and beyond. Scientists paved the way with passports to guarantee safe passage (it didn’t always work), dispatched instructions across the globe on how to view the transit, and instrument makers worked around the clock to provide them with the best telescopes.

One of the most important locations during the transit in June 1769 was California (then in Spanish hands) because the entire transit would be visible there. Because the Spanish had pretty much ignored the first transit, the French decided to organize their own expedition under the command of Jean-Baptiste Chappe d’Auteroche, an astronomer who had observed the first transit in Siberia. The Spanish king was willing to cooperate and provided the necessary permission and even a vessel to get the French from Europe to the Americas.

Chappe’s voyage was beset by problems. First he was stuck in Spain for more than two months in a bureaucratic tug of war; then he couldn’t find a ship; and when he eventually found one in December 1768, it was so small that everybody worried he would never survive a winter Atlantic crossing. When Chappe finally arrived in Veracruz, Mexico, he found himself in the midst of a hurricane. Then he had to cross Mexico on mules to reach San Blas at the western coast and from there catch a boat to Baja California. And he was not traveling lightly: His instruments alone weighed more than half a ton.

When he reached Baja, it was the end of May, only a few days before the transit on June 3. In a rush he set up his observatory at a typhus-ridden Jesuit mission. “I cared little,” he said, “whether it was inhabited or deserted,” but it was a decision he would pay for with his life. He observed the transit and made the measurements, but after he had taken his last notes — already delirious with fever — he died and was buried at the mission. Chappe’s assistant was able to deliver his observations to the Academy of Sciences in Paris, where they were added to the other data more than a year later.

Others were luckier: Capt. James Cook returned to Britain on the Endeavour with good results from Tahiti, as did the astronomers who observed the transit at the Arctic Circle, Hudson Bay and in Russia, among many other places. It took until the summer of 1771 for the hundreds of observations to be collected. When the calculations were done, it was determined that the distance from Earth to the sun was between 92.9 million and 96.9 million miles, impressively close to today’s reckoning of 92,960,000 miles.

The scientists’ achievement was astonishing; their adventures exciting. But most amazing of all was that they succeeded in working peacefully together. The idea of the modern scientific expedition was born. From then on every major exploration — from Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who received detailed scientific instruction, to Charles Darwin on the Beagle — included a scientific team. “The science of two nations may be at peace,” one of the transit scientists said, “while their politics are at war,” and it is this peace of the sciences that remains as important today as it was then.

So in honor of the intrepid astronomers of the 18th century, prepare to watch Venus march across the sun. The transit starts at 3:06 p.m. and can be seen until the sun sets at 8 p.m. (it actually will end in darkness at 9:47 p.m.). Don’t look into the sun without protection. If you have sharp eyes, just buy some cheap eclipse shades, or fit your binoculars or telescope with appropriate filters.

Unlike Chappe, we don’t have to risk our lives to make the observation. We only have to hope for clear skies.

Andrea Wulf is the author of “Chasing Venus. The Race to Measure the Heavens.”