Amid reform movement, some GOP-controlled states give police more power

- Share via

COLUMBUS, Ohio — After a year of protests over police brutality, some Republican-controlled states have ignored or blocked police-reform proposals, moving instead in the other direction by granting greater powers to officers, making it harder to discipline them and expanding their authority to crack down on demonstrations.

The sponsors of the GOP measures acted in the wake of the nationwide protests that followed George Floyd’s murder, and they cited the disturbances and destruction that spread last summer through major U.S. cities, including Portland, Ore.; New York; and Minneapolis, where police killed Floyd.

“We have to strengthen our laws when it comes to mob violence, to make sure individuals are unequivocally dissuaded from committing violence when they’re in large groups,” Florida state Rep. Juan Fernandez-Barquin, a Republican, said during a hearing for an anti-riot bill that was enacted in April.

Florida is one of the few states this year to both expand police authority and pass reforms: A separate bill awaiting action by the governor would require additional use-of-force training and require officers to intervene if another uses excessive force.

Los Angeles has reopened, but many first responders remain unvaccinated. Just over 50% of the city’s firefighters and police officers have gotten one shot.

States where lawmakers pushed back against the police-reform movement included Arizona, Iowa, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Wyoming, according to an Associated Press review of legislation.

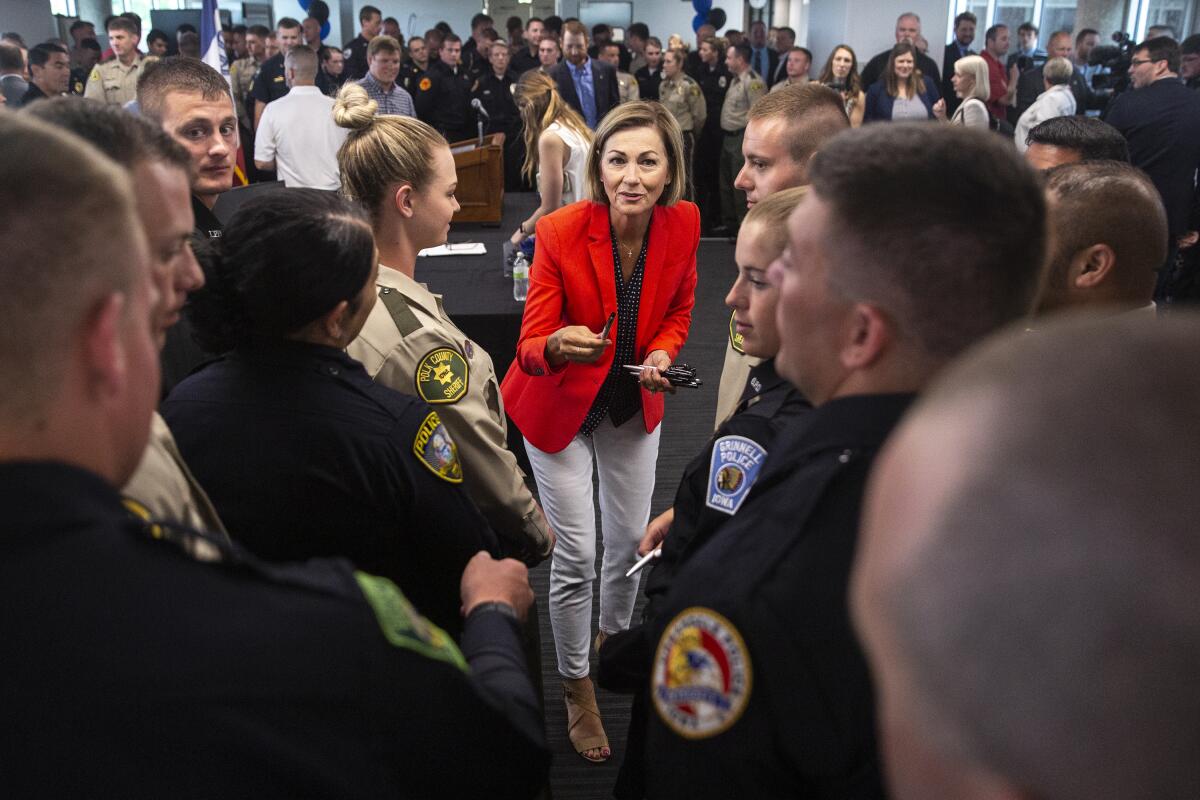

Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds signed a bill Thursday to expand qualified immunity for police officers and enhance penalties for protesters, including elevating rioting to a felony.

“This is about protecting law enforcement and giving them the tools they need to keep our communities safe and showing them that we have their back,” said state Rep. Jarad Klein, a supporter of the bill.

The bill passed the GOP-controlled Legislature despite promises last summer by the Republican governor and GOP legislative leaders to try to end discriminatory police behavior and adopt other criminal-justice reforms.

Reynolds introduced measures at the start of the 2021 legislative session to ban racial profiling by police and establish a system for tracking racial data on police stops. Both ideas were recommended by a task force the governor appointed in November 2019.

Instead, Republican lawmakers left out those proposals and pushed through the new bill.

Reynolds acknowledged that she doesn’t always get what she wants, even from her own party. She plans to reintroduce the measures next year, a spokesperson said.

Reform advocates found the quick reversal by Iowa Republicans disappointing.

“Would it have been too hard to do the right thing?” Democratic state Rep. Ras Smith asked during a floor debate over the bill. “You decided to make this an either-or, to trample on freedom, to show support for law enforcement in ways that they didn’t even ask for.”

After Floyd’s death, Oklahoma Democrats tried to seize on the protest movement to pass bills that would ban the use of chokeholds, provide uniform guidance for body cameras and create a database of police use-of-force incidents. But none of those proposals even received a hearing. One GOP lawmaker called them unnecessary after the measures faced opposition from rank-and-file officers, prosecutors and county sheriffs.

Instead, the Republican-dominated legislature passed laws to grant immunity to drivers whose vehicles strike and injure protesters on public streets and to prevent the “doxxing,” or releasing of personal identifying information, of law enforcement officers if the intent is to stalk, harass or threaten the officer.

“I was a little disappointed because these were simply accountability measures” aimed at “making sure the public understands what happens when something goes wrong,” said state Rep. Monroe Nichols, a Democrat whose father and uncle were police officers.

In Wyoming, Democratic state Rep. Karlee Provenza introduced a bill that would have forbidden officers who are dismissed for misconduct from being hired by another law enforcement agency. Her bill passed the House but failed in the Senate, which are both controlled by Republicans.

“If the conversation is, ‘This is an anti-policing bill,’ rather than, ‘This is an accountability bill,’ it has a steeper hill to climb,” Provenza said.

Byron Oedekoven, executive director of the Wyoming Assn. of Sheriffs and Chiefs of Police, said the measure was not needed. Law enforcement, he said, already does a good job vetting officers, including following hiring standards in state law and voluntarily reporting officers who are decertified to a national database.

While cities across the U.S. were creating or expanding civilian police oversight boards, Republican governors in Tennessee and Arizona signed into law measures that could reduce the independence of those boards. The GOP laws require board members to complete hours of police training or mandate that a majority of board positions be filled with sworn officers. Critics say such steps defeat the purpose of civilian oversight.

The review boards were intended to address concerns, especially in Black communities, that police departments have little oversight outside their own internal review systems, which often clear officers of wrongdoing in fatal shootings.

“It has all the trappings of making it look like the fox is watching the henhouse here,” Arizona state Sen. Kirsten Engel, a Democrat, said of that state’s measure.

Some states continue to introduce bills to protect police, including recent proposals in Ohio and Kentucky that would make taunting or filming a police officer a crime. But about half of states have embraced at least some reform measures.

Since May 2020, at least 67 police reforms have been signed into law in 25 states, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Those laws addressed neck restraints and chokeholds, body cameras, disciplinary and personnel records, and independent investigations, among other reforms.

At least 13 states enacted restrictions on the use of force, and at least eight have implemented laws beefing up officer reviews and investigations, according to the NCSL data.

Minnesota banned chokeholds. Colorado became the first state in the country to strip police of qualified immunity. Washington enacted a dozen police-reform laws, including restricting the use of no-knock warrants and designating an independent investigator for fatal police shootings. Even GOP-dominated Texas, where Floyd’s body was laid to rest, implemented more uniform disciplinary actions for officer misconduct.

Some Democrats in Republican-controlled states have become discouraged in their quest to change the justice system.

“We just hit so many roadblocks,” said South Dakota Rep. Linda Duba, a Democrat who was part of a coalition to pass reforms.

In the reckoning over Floyd’s death, there seemed to be momentum to reevaluate the role of policing in minority communities, Duba said, but the issue steadily calcified along political lines.

“It’s happening slowly because we live in a state where people are either not exposed to it, don’t believe it happens or believe it’s unpatriotic to criticize law enforcement,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.