- Share via

JAKARTA, Indonesia — Sri Siti Marni was 11 years old when her aunt introduced her to a wealthy acquaintance from Jakarta who promised to take her in and pay for her schooling.

It was a generous offer, delivered unexpectedly. Marni’s parents couldn’t refuse. Her father, who made a living as a driver, deliveryman and parking lot attendant, struggled to raise eight children. Marni, his eldest, had no hope of a better life without continuing her education.

Marni packed clothes and hijabs and left her hometown of Bogor, on the outskirts of the Indonesian capital. The door opened to the family of Meta Hasan Musdalifah, a former singer, who told Marni to call her “Mama” and to treat her four children as siblings. Marni felt like she was going on a long vacation.

But as the months passed, Musdalifah never mentioned school. The welcoming of those early days turned to cruelty. Marni was ordered to clean, iron and cook. When she didn’t finish her chores correctly or fast enough, Musdalifah would scream and hit her.

“I begged them many times to send me back but they refused,” said Marni, now 25. “I was very young at that time and I was all alone, so I obeyed them to avoid any trouble.”

Born Into Danger

This is the first in a series of occasional stories about discrimination and human rights abuses faced by women in Indonesia.

What followed was nine years of abuse that left Marni traumatized and physically disfigured in a case that drew national attention to the way millions like her are coerced and exploited as domestic workers, one of the most common sources of employment for impoverished Indonesian girls and young women. Some girls die. Others are maimed, and many languish for so long they grow into women and are forgotten.

Marni was imprisoned in Musdalifah’s home and subjected to daily beatings. She was forced to eat cat feces, doused with boiling water and seared with an iron. She worked for no pay and was never given time off. She never spoke to her parents; never stepped outside.

There seemed no escape. Marni was locked in the bathroom whenever Musdalifah and her family left the house. She lost count of the number of times she tried to take her own life.

In February 2016, Marni was beaten once again by Musdalifah for hours. She blacked out in her bedroom; her mouth filled with blood. When she woke up the next day, she noticed the door to the roof was left unlocked.

She sprang for the opening and climbed down the side of the house clinging to an antenna cable. Marni then scaled a gate and ran until she found a police station. She appeared before the officers as a ghost-like figure drowning in an oversized T-shirt. Her cheeks were badly swollen. Her lip was split. She was so malnourished by then that she looked about 12 despite being eight years older.

“There are scars all over my body; on my back, chest, thighs and sides,” said Marni, who was married in October and is expecting her first child. “They do not hurt anymore, but every now and then when I’m alone, the memories of those years come back and I can’t help but cry.”

Marni’s ordeal is unusual, not because of the brutality of her treatment, but because her abuser was tried as a criminal. Musdalifah was sentenced to six years in prison for torture. Three domestic workers who were also abused by Musdalifah testified as witnesses for prosecutors. Charges were never filed against Musdalifah’s husband, who Marni said was complicit in her treatment.

Most cases of abuse go unnoticed. Employers often shield servants from the public or present them as distant relatives under their care — a Javanese tradition known as ngenger — so that neighbors dismiss signs of conflict as a private domestic matter.

Marni’s case is held up by rights activists as an example of the worst that can happen when girls and young women are pried from their homes and thrown into a role that has no legal protections or formal recognition. Domestic workers often toil seven days a week, work excessive hours and earn a fraction of the minimum wage. Teenagers are favored, but girls as young as 10 have been found to be recruited as servants.

“The younger they are, the easier they are to manipulate,” said Siti Zuma of the Legal Aid Foundation of the Indonesian Women’s Assn. for Justice. “They cannot fight back, especially when they are alone and so far away from home. Parents see the employers as heroes who have higher social status and can give their children a better life.”

Many are hired through recruitment agencies, but it is not uncommon for others to become domestic workers the way Marni did: through family connections and promises of schooling.

Indonesia’s threadbare rural education system ensures there’s a steady pipeline of girls to enlist. The country is not unlike other Asian countries, including Myanmar, Cambodia and Sri Lanka, with vast pools of impoverished females who often fall prey to forced servitude and human trafficking.

A bill designed to recognize and safeguard domestic workers has languished for 17 years amid the political deal-making that regularly stalls lawmaking in Indonesia.

Policymakers have resisted imposing standards by reasoning it would be impossible to monitor working conditions inside homes and by arguing that domestic workers are more like “helpers” than skilled laborers who require legal status. Activists say such attitudes would be different were the workers predominantly male.

“Most of the domestic workers are women, so from the point of view of a patriarchal culture like ours, they are just doing ‘women’s work,’” said Theresia Iswarini, a member of the National Commission on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. “Their skills are discredited and their work isn’t recognized as real work.”

Indonesia’s workforce is dominated by men because of a deeply entrenched patriarchal culture. Government data show 83% of working-age males are employed compared with only 53% of working-age females. On average, females received 23% less pay than men.

Without protections, the job of domestic worker is fraught with risk for some of the most vulnerable people in the world’s fourth-most populous country — a widely uneven society where wealth and cultural influence are concentrated on the island of Java and its political and financial center, Jakarta.

In another high-profile case, a villager from West Java was beaten and starved to death by her employer. Linawati, who like many Indonesians went by one name, was 16 when she started working for a family in north Jakarta. She was forbidden to return home and wasn’t seen by her family until 2019, after her body appeared at a funeral home. Workers there grew suspicious when they spotted bruises on Linawati and called police. An investigation revealed Linawati had been abused and locked inside her employer’s bathroom for days without food before she died.

That same year, a domestic worker in Bali fled her employer after she doused her with boiling water in a fit of rage for losing a pair of scissors. Eka Febriyanti, who was 21 at the time, suffered injuries to her head, back, arms and legs.

In May, a 45-year-old domestic worker in Surabaya, a city in East Java, was discovered by social workers with burn marks and bruises. Elok Anggraini Setyawati was found to have been beaten and tortured by her employer, an attorney, for almost a year. During that time, she earned only a month’s salary: $104.

Officials say such cases are isolated, but activists believe they’re probably on the rise because of the growing number of women and girls being funneled into domestic work. Indonesia’s domestic workers number between 4 million and 11 million, depending on which labor organization you ask. Getting a more precise tally is difficult, given the informal nature of the job.

Experts say demand for domestic workers has soared in tandem with Indonesia’s middle class, which has grown to 20% of the population of 270 million from 7% in 2005. The introduction of millions of new low-wage workers who can cook, clean and look after children has freed up more households to include two working spouses, helping power Indonesia’s steady economic growth.

Until the pandemic, Indonesia had been one of the most promising economies in Southeast Asia, a product of its vast natural resources and growing manufacturing base. The boom led to a surge in private car ownership, high-rises and domestic tourism.

“Domestic workers have had to sacrifice themselves for the nation’s development,” said Lita Anggraini, coordinator of the National Network for Domestic Worker Advocacy, also known as Jala PRT. “They are left behind. They have to keep working hard so other people can live well but they are not allowed to demand their rights.”

Without contracts, domestic workers were some of the first to be laid off last year when the pandemic first swept across Indonesia, sending unemployment to its highest level in a decade.

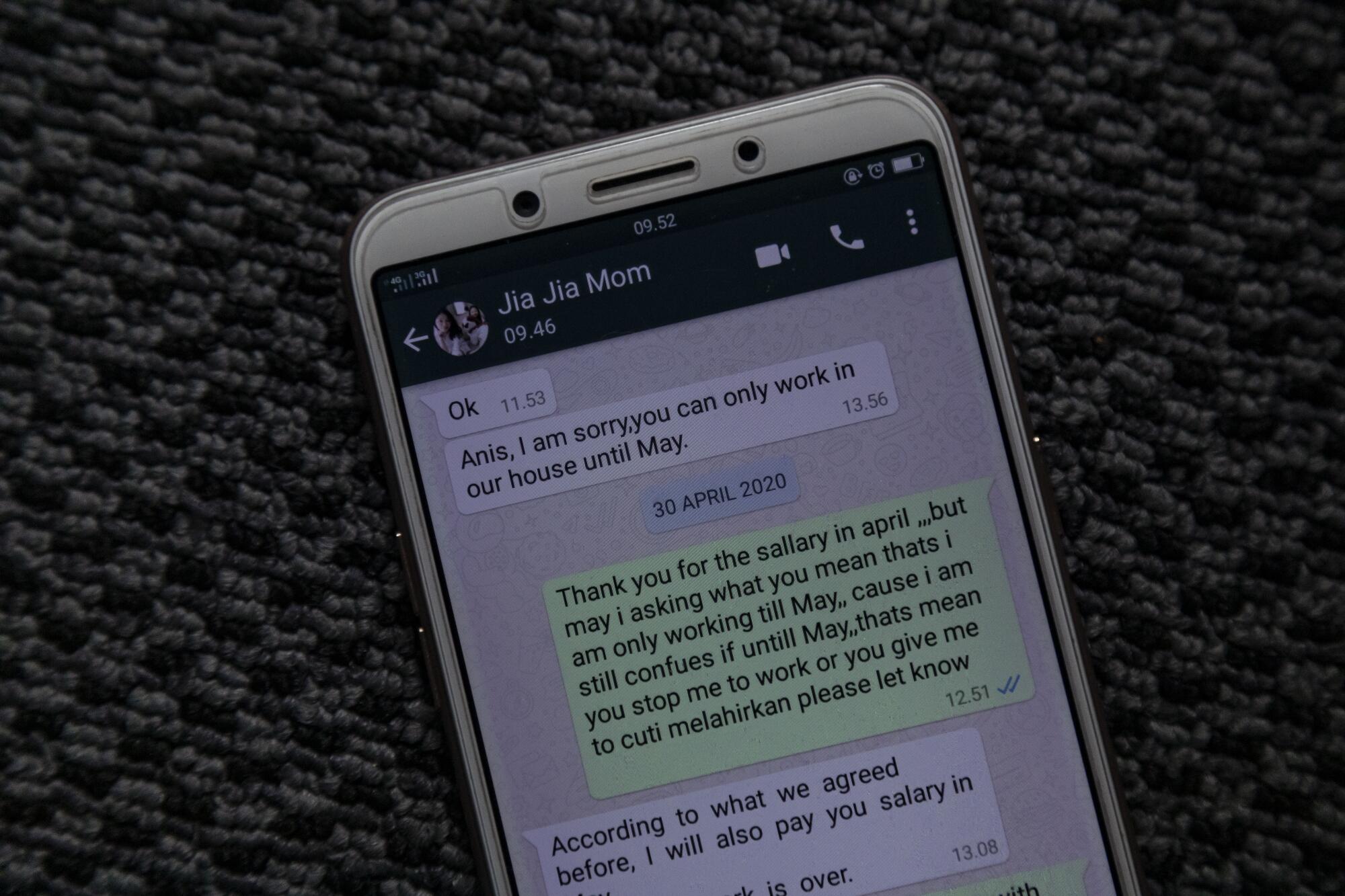

Nanik Supartini’s employer fired her with a text message in April 2020, citing the pandemic. The 40-year-old has been looking for work since. With her savings dwindling, Supartini is unsure how she’ll pay for rent and necessities. She had to tell her oldest child she could no longer afford to send her to university.

“She understands our situation, but it really saddens me because my daughter is a bright student,” Supartini said. “She is always at the top of her class. I always dreamed that my children would have a better life by going to university.”

Like many housemaids in Indonesia, Supartini did not finish her basic education. She graduated from junior high school when she was 14 and has worked in one house after another since then.

“I want to continue working as a domestic worker because this is what I have been doing for 26 years,” she said.

Supartini lives in a room in south Jakarta packed with furniture and refrigerators she’s storing for other unemployed domestic workers who have returned to their villages. She shares one bed with her husband, 7-month-old daughter and her friend’s 6-year-old girl, whom she’s been taking care of since January as her mother works. The pandemic has only worsened the position of domestic workers. Supartini said friends and family have agreed to take on even longer hours and lower pay, including as little as $42 a month. They’ve also agreed to not travel home to reduce the risk of transmission.

Supartini has supported campaigns to recognize domestic workers, but is losing hope women like her will ever be treated fairly.

“We are not helpers, we are workers,” she said. “Even before the pandemic we were invisible. We work very hard but people don’t see us as workers, they see us as servants. When we ask for better pay or for basic rights, they look at us bewildered, like they don’t think we deserve it.”

Marni knows about that kind of injustice. But she now lives in peace with her husband in Bogor. She had worked as a masseuse before the pandemic, but lockdown restrictions have kept her from doing so.

“I’m happier and doing so much better now.... Inshallah, I would try my best to never work as a domestic worker again,” she said in a recent interview where she displayed round-shaped scars on her nose and a deformed lip from the countless blows.

From time to time, Marni is asked by women’s rights organizations to give a speech to domestic workers in seminars, webinars or discussion forums. It’s cathartic, she said, a way to turn her horror into something that will help women and girls find better lives.

“I don’t want anyone else to experience what I experienced,” Marni said.

Times staff writer Pierson reported from Singapore and special correspondent Cahya from Jakarta.

(This is the first in a series of occasional stories about discrimination and human rights abuses faced by women in Indonesia. The story was supported by a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation.)

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.