China records its first population decline in decades as births drop

- Share via

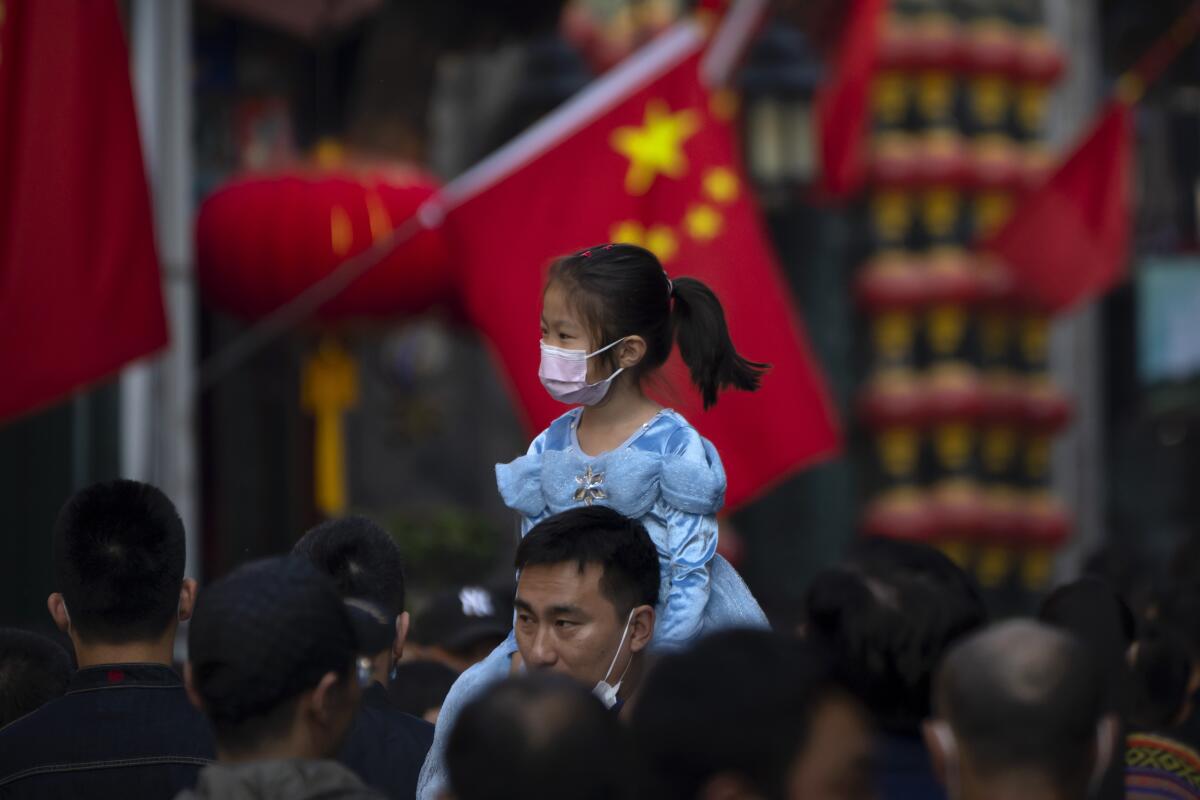

BEIJING — China’s population shrank last year for the first time in decades as its birthrate plunged, official figures showed Tuesday, adding to pressure on leaders to keep the economy growing despite an aging workforce and at a time of rising tension with the U.S.

Despite the official numbers, some experts believe China’s population has been in decline for a few years — a dramatic turn in a country that once sought to control such growth through a one-child policy.

Many wealthy countries are struggling with how to respond to aging populations, which can be a drag on economic growth as shrinking numbers of workers try to support growing numbers of elderly people.

China’s economy is slowing and its population is aging. Will that prompt its leaders to take risks now, before their power declines?

But the demographic change will be especially difficult to manage in a middle-income country such as China, which does not have the resources to care for an aging population in the same way that one like Japan does. Over time, that will probably slow the Chinese economy and perhaps even the world’s, and could potentially keep inflation higher in many developed economies.

“China has become older before it has become rich,” said Yi Fuxian, a demographer and expert on Chinese population trends at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

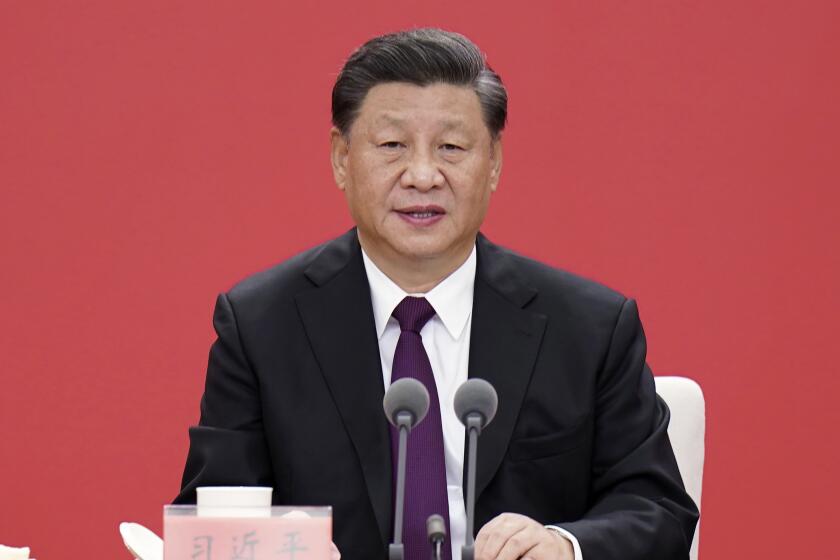

A slowing economy could also pose a political problem for the ruling Communist Party, if shrinking opportunities foment public discontent. Anger over strict COVID-19 lockdowns, which were a drag on the economy, spilled over late last year into protests that in some cases called for leader Xi Jinping to step down — a rare direct challenge to the party.

The National Bureau of Statistics reported Tuesday that the country had 850,000 fewer people at the end of 2022 than the previous year. The tally covers only the population of mainland China, excluding Hong Kong and Macao as well as foreign residents.

Compared with 2021, the number of babies born last year decreased by more than 1 million amid a slowing economy and widespread pandemic lockdowns, according to official figures. The bureau reported 9.56 million births in 2022; deaths ticked up to 10.41 million.

It was unclear whether the population figures were affected by a widespread COVID-19 outbreak after the easing of pandemic restrictions last month. China recently reported 60,000 COVID-related deaths since early December, but some experts believe the government is probably underreporting deaths.

The last time China is believed to have recorded a population decline was during the Great Leap Forward campaign launched at the end of the 1950s. Then-leader Mao Zedong’s disastrous drive for collective farming and industrialization led to a massive famine that killed tens of millions of people.

China’s population has begun to decline nine to 10 years earlier than Chinese officials predicted and the United Nations projected, said Yi, the demographer. At 1.4 billion, it has long been the world’s most populous nation, but is expected to soon be overtaken by India, if it has not been already.

China has sought to bolster its population since officially ending its one-child policy in 2016. Since then, it has tried to encourage families to have second or even third children, with little success, reflecting attitudes in much of East Asia where birthrates have fallen precipitously. In China, the expense of raising children in cities is often cited as a factor.

Facing the consequences of a plummeting birthrate, China will now allow couples to have a third child just a few years after limiting them to one.

Zhang Huimin bemoaned the “fierce competition” young people face these days — a fairly typical attitude among her age group in terms of starting a family.

“Home prices are high and jobs are not easy to find,” said the 23-year-old Beijing resident. ”I enjoy living by myself. When I feel lonely, I can take pleasure in staying with my friends or keeping pets.”

Yi said his research shows China’s population has been declining since 2018, meaning that the population crisis is “much more severe” than previously thought. China now has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, comparable only with Taiwan and South Korea, he said.

That means that China’s “real demographic crisis is beyond imagination and that all of China’s past economic, social, defense and foreign policies were based on faulty demographic data,” Yi said.

China’s looming economic crisis will be worse than Japan’s, where years of low growth have been blamed in part on a shrinking population, he said.

China’s statistics bureau said the working-age population between the ages of 16 and 59 totaled 875.56 million, accounting for 62% of the national population, while those ages 65 and older totaled 209.78 million, accounting for 14.9% of the total.

It also reported China’s economic growth fell last year to its second-lowest level in at least four decades, although it is picking up after the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions that kept millions of people at home.

After loosing anti-virus controls amid protests, China tries to strengthen hospitals and set up more intensive-care facilities.

As COVID-19 rips through China, other countries and the World Health Organization are calling on its government to share more comprehensive data. Is it doing enough?

Any slowdown has wider implications. China became a global manufacturing powerhouse in the early 2000s. With millions of its citizens flocking from the countryside to its cities, China’s seemingly endless supply of cheap labor lowered costs for consumers around the world for computers, smartphones, furniture, clothes and toys.

Its labor costs have already begun to rise — and changing demographics will probably accelerate that trend. As a result, inflation could creep higher in countries that import Chinese goods, though production may also move to lower-cost countries such as Vietnam, as it already has.

On top of the demographic challenges, China is increasingly in economic competition with the U.S., which has blocked the access of some Chinese companies to American technology, citing national security and fair competition concerns.

If handled correctly, a declining population does not necessarily lead to a weaker economy, said Stuart Gietel-Basten, professor of social science at Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi.

“It’s a big psychological issue. Probably the biggest,” Gietel-Basten said.

According to the data from the statistics bureau, men outnumbered women by 722.06 million to 689.69 million, a result of the one-child policy and a traditional preference for male offspring to carry on the family name.

The statistics also showed increasing urbanization in a country that traditionally had been largely rural. Over 2022, the permanent urban population increased by 6.46 million to reach 920.71 million, or 65.22%, while the rural population fell by 7.31 million.

The U.N. estimated last year that the world’s population reached 8 billion on Nov. 15 and that India will replace China as the most populous nation in 2023. India’s last census was scheduled for 2022 but was postponed due to the pandemic.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Gietel-Basten said China has been adapting to a demographic change for years by devising policies to move its economic activities up the value chain of innovation, pointing to the development of semiconductor manufacturing and the financial services industry.

“The population of India is much younger and is growing. But there are many reasons why you wouldn’t necessarily automatically bet your entire fortune on India surpassing China economically in the very near future,” he said.

Among India’s many challenges is a level of female participation in the workforce that is much lower than China’s, Gietel-Basten added.

“Whatever the population you have, it’s not what you’ve got but it’s what you do with it … to a degree,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.