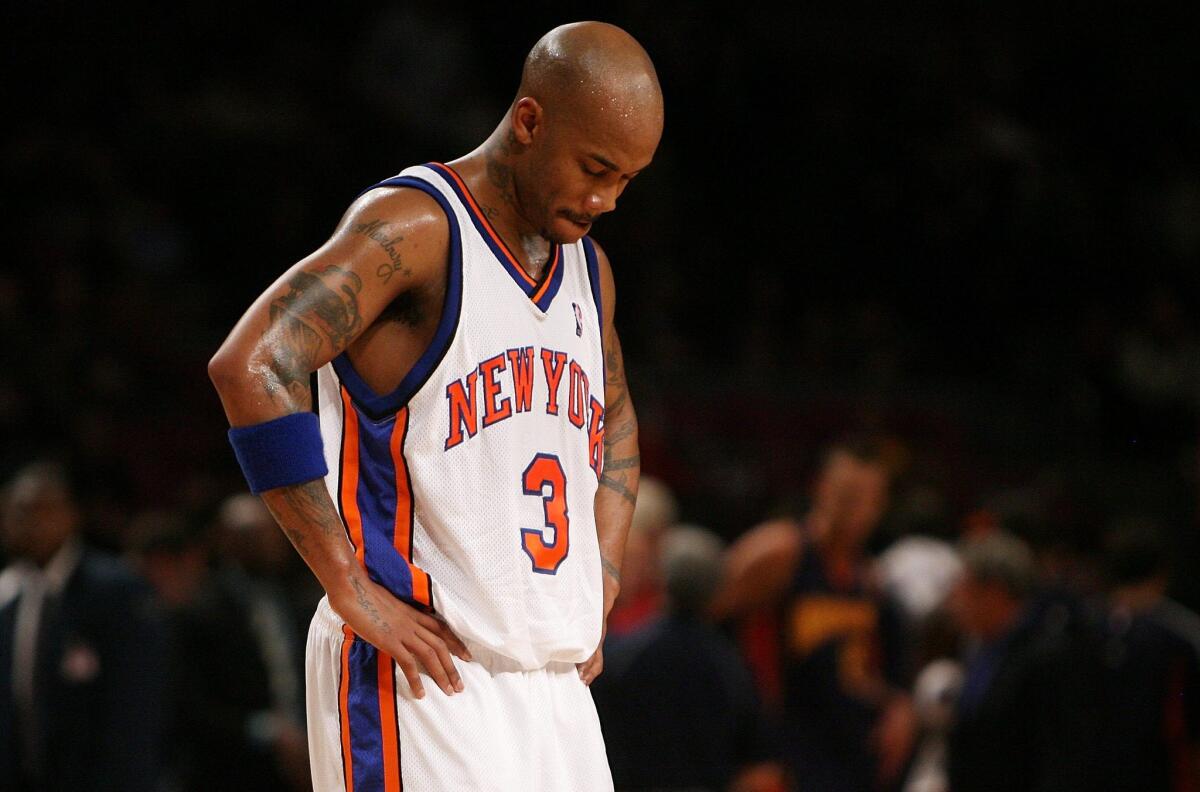

Stephon Marbury: From NBA bad boy to Chinese celebrity

- Share via

Reporting from Beijing — Five years ago, Stephon Marbury’s basketball career looked to be at a dead end. His spats with two New York Knicks coaches had led to their firings; he had been banned by the team; journalists branded him the “most reviled” athlete in New York.

He even turned down a $1.3-million contract offer from the Boston Celtics, calling it “disappointing.”

Today, the former NBA All-Star has reinvented himself in China as a friendly, inspirational man of the people who uses “love is love” as his new motto on social media. On top of making more than $2 million a year from his Chinese basketball team, Marbury has published a book, is set to appear in a stage musical beginning Wednesday, and has a movie in the works.

“This is just how my life is written. It’s supposed to go this way. This is part of what is supposed to happen,” Marbury said in an interview Sunday after a rehearsal of “I Am Marbury: The Evolution of a Lone Wolf.”

The musical’s saccharine theme concerns how Marbury’s success in the Chinese capital has inspired millions of young migrants to continue to go after their own dreams. It will debut at Beijing’s MasterCard Center, which hosted basketball games during the 2008 Olympics, as 1.3 billion Chinese start celebrating their seven-day National Day holiday. Tickets range from $30 to $310.

After leading his Beijing Ducks, the city’s professional basketball team, to two championships in three years, Marbury has become a household name in a city that has more than 8 million migrants. Those migrants are usually referred to as a bei piao, which means “floating in Beijing,” conjuring an image of a person floating like a bottle in the big ocean that is Beijing, a city of 20 million.

“From the lowest point of his life, Marbury came to China and then to Beijing, where he made a comeback in life and changed his life completely,” said Yang Yi, who introduced Marbury to China and has been acting as his agent. “He became really successful in this city. We feel that his story could touch a lot of people in Beijing, because many people have a similar experience here.”

Although Marbury arrived in Beijing in far different financial circumstances than the city’s typical young migrants, he still thinks he can relate to them. “Coming to Beijing, throughout all of what has happened and the success I have gained, I look at it as I was just fortunate and blessed,” Marbury said. “To be able to endure, accept and embrace the culture, allowed me to just become a bei piao.”

::

Marbury had no intention of coming to China after his turbulent career in the NBA ended in 2009. He was in Houston visiting a trainer when an agent from Yang’s company reached out to him.

“Our first phone conversation with Marbury lasted over one hour. He cried when he talked about his experience in New York and how he eventually reached the lowest point of his life,” Yang said. “He even thought about quitting and not playing basketball anymore.”

The emotion Marbury displayed during the phone conversation came as a shock, said Yang, who was aware of the athlete’s reputation as a “lone wolf” and troublemaker from news reports. “Before we thought he was more like a monster, but then we understood that he’s very sincere and even fragile. We felt that he’s really a great person,” Yang said.

Still, Marbury was hesitant and Yang was wary. Was it worth it, Yang wondered, to bring a player with such a reputation to China? Would it be a mistake to try to pair him with the Chinese teams with which Yang had tried to build good relationships?

Almost three months after Marbury’s initial phone conversation with the Chinese agent, a Chinese Basketball Assn. team showed interest in Marbury. The team, then known as the Shanxi Zhongyu Brave Dragons, was halfway through its season and had lost 10 of its first 12 games. The Dragons were ready to take a gamble on Marbury.

Marbury took to the task with surprising seriousness. He asked for four weeks of preparation time, then joined the team in January 2010 and helped it win six of the 15 games in which he played. His efforts on the court won the hearts of his new teammates and new head coach.

But Shanxi’s romance with Marbury proved short-lived. Though the team’s boss promised Marbury would be signed for a second season, the Dragons got a new general manager and a new head coach in the off-season; they decided not to retain Marbury. But to prevent a major competitor from signing him, the Dragons waited to notify Marbury until he had returned to Shanxi with his luggage – just two weeks before the new season was set to start.

A frustrated Marbury locked himself in his hotel room in Shanxi. He ended up signing with the mediocre Foshan Long Lions, as all the good teams had already filled their rosters.

Finally wise to the ways of the league, Marbury landed with the Beijing Ducks the next season. He led them to their first CBA championship in his first season with the team in 2012 and again this year.

::

In addition to his CBA paycheck, Marbury has signed endorsement deals valued far above his $2-million annual salary with sponsors including Chinese property developer Vanke, energy drink maker Red Bull, Japanese watch brand Casio and Chinese footwear producer 361 Degrees. But it’s not just his achievements on the court that have made him one of the most commercially successful foreign athletes in China; it’s also his carefully cultivated and re-crafted public image.

In a first-person column for the state-run China Daily newspaper in 2011, Marbury wrote: “I love my new life in Beijing. My heart is filled with love for my new extended family -- the billion-plus people in China who have shown me nothing but unconditional love.”

Before playing his first game with his new team in Beijing, Marbury took the city’s subway to team practice every day for more than a month. He also jogged with elderly people in the popular Temple of Heaven in the morning and went to “crosstalk” shows favored by many locals in the evening, even though he couldn’t understand a word of the rapid-fire Mandarin-language puns.

And he has tried to use simple Chinese phrases like ni hao (hello) whenever he greeted fans.

“We did give him some suggestions. But most basketball stars would probably say no,” Yang said.

In April, Marbury was named “an honorary resident of Beijing,” receiving the award from Mayor Wang Anshun. Fans have given him nicknames such as “Ma Zhengwei,” which means “Political Commissar Ma,” for the leadership he showed on the court and “Lao Ma,” a way Chinese address their close friends. His account on China’s Twitter-like social media site Weibo has more than 3.5 million followers.

His commercial success in China has extended beyond endorsement deals. In addition to an autobiography in Chinese, “I Am Political Commissar Ma,” and the musical, Marbury is planning to take a lead role in a movie that is expected to start filming in April in China.

The movie is based on a script originally titled “Far East Basketball Team” from a writer based in Hollywood, and is expected to be distributed in China by Wanda Group, which bought AMC theaters in the U.S. two years ago.

The story is very similar to Marbury’s experience in China, although the NBA star he plays in the movie will lead a team in a third-tier Chinese city to a championship.

“I’m excited about the movie. Acting is definitely something I want to do after I finish playing basketball,” Marbury said after a crash course in acting during the open rehearsal of the musical Sunday.

Not that he’s quitting the court immediately. Marbury still has two years left on his contract with the Ducks. He hasn’t decided whether he’ll retire after that. He also said he plans to coach a Chinese team.

Marbury had returned to Beijing just one day before Sunday’s rehearsal. He was given only 30 minutes to get familiar with the script before he had to perform in front of a group of 50 reporters.

“I am Marbury. We are all Marburys. We’re all proud of ourselves,” young Chinese dancers chanted as the real Marbury read from the script. As hip-hop Chinese music blasted through the speakers, Marbury showed off his dance moves.

“I know I made mistakes. I think the most important thing is repetition. I’ll work hard until I get it right,” Marbury told reporters after the rehearsal, and then he posed for pictures and signed autographs.

Tommy Yang in The Times’ Beijing bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.