‘Poor but sexy’ Berlin now home to soaring rents and rising tensions

- Share via

Reporting from BERLIN — Thirty-two years after moving into her cozy one-bedroom apartment near Berlin’s city center, Brigitte Lustig is about to be evicted — a fate the 61-year-old never imagined in a city renowned for its cheap rents and bohemian spirit.

“I was born just up the street and lived here my whole life,” she said, the fear and frustration tangible. “Why should I be forced out? I never thought this could happen to me. I thought I was safe.”

Lustig’s looming expulsion is a rarity in Germany, where renters enjoy extraordinary protection and considerable clout while the rights of property owners are restricted and controlled. It’s difficult to cancel leases and nearly impossible to evict a tenant who pays rent on time.

Lustig pays $300 a month from her $800 disability check for the 570-square-foot apartment, located in a newly fashionable district only a mile from Tiergarten, a leafy city park that’s one of Berlin’s most popular.

Her new landlord, who paid $60,000 for the apartment, first tried to get her to leave in 2015 so his sister could move in. When the sister died during his protracted dispute with Lustig, he decided to take advantage of the suddenly overheated rental market and find a new tenant, or — barring that — a buyer.

Lustig said she couldn’t afford another place to live, with apartments in the city now going for more than double what she paid. She turned to the courts for relief.

“Tenant protection is important in Germany and it’s a completely different situation than in the United States,” said Lustig’s lawyer, Christoph Mueller. “As long as you pay your rent on time and don’t do anything ridiculous like start a fire in the living room, it’s really hard to cancel the lease. That’s a great social achievement in Germany and we don’t want any change to it.”

But, on a technicality related to the death of the owner’s sister, a city court ruled against Lustig, an outcome that quickly became a catalyst for a renter’s rebellion in Berlin.

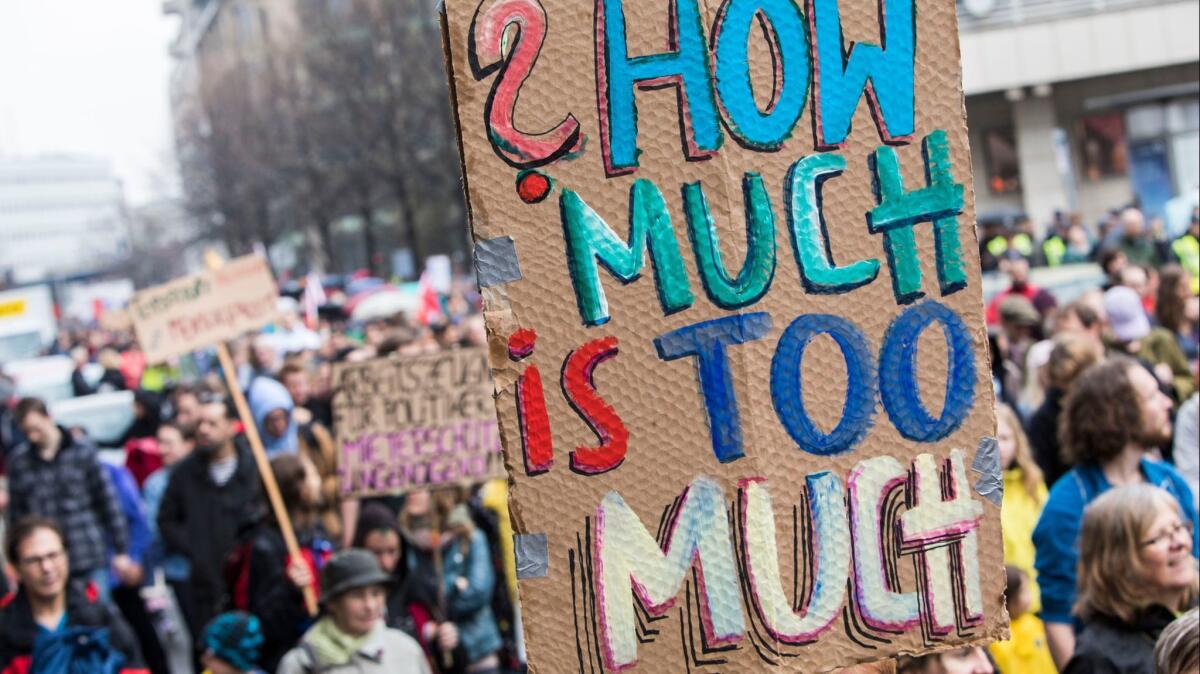

Tens of thousands took to the streets this month to demand increased political action to combat rapidly rising rents and surging property prices. Until recently, Berlin was famous for its affordable housing and proud of a motto coined in 2003 by former Mayor Klaus Wowereit: “Berlin is poor, but sexy.”

Growing in size and volume, the ongoing demonstrations for tougher rent control and more low-income housing are now shaping political forums and making newspaper headlines, in part because — unlike in many large cities — the overwhelming majority of Berlin voters are renters.

About 85% of Berlin’s 3.4 million residents live in rentals and homeownership remains remarkably low — a condition fostered by the city’s turbulent history, Cold War division and five decades of communist rule in East Berlin. Almost by nature, Berliners tend to have a low regard for property owners.

The reunified capital city also has a proud tradition of heavy state support for low-cost housing for the working classes. Generations of mayors from all political parties have wholeheartedly backed the notion that nurses, teachers, police officers, firefighters and other workers with ordinary incomes need to be able to afford to live in the heart of the city.

Real estate investors had long avoided Berlin, which has little industry to speak of, relatively high unemployment and an abundance of low-income workers. Property prices actually fell in some areas during parts of the 1990s and the first decade of the new millennium. And in a move it now regrets, the deeply indebted city sold off more than 220,000 of its 360,000 rent-subsidized social housing units when prices were depressed.

But all that has begun to change as investors — many of them foreign interests — snap up entire apartment complexes at bargain basement prices.

Though still modest compared with other cities in Europe, rents in Berlin have risen 75% in the last five years. A recent survey by the property consultant group Knight Frank showed that property prices in Berlin rose 21% in 2017, the steepest rate in its survey of 150 cities around the world and far above the average increase of 4.5%. The biggest increases that year in the United States were Seattle, where rents rose 12.7%, and San Francisco, where they were up 9.3%.

“We don’t want Berlin to become a city for only rich people,” said Ulrike Hamann, a 42-year-old sociology professor at Berlin’s Humboldt University who marched with 21,000 others in the recent rent protest.

“We know global capital has discovered Berlin and is getting into the market here. But Berlin has always been a city of renters and we have the tools to fight to keep it that way,” she said.

“There’s nothing wrong with investors who buy apartments with the idea of earning a small profit someday,” said Rainer Wild, the managing director of the Berliner Mieterbund renters association. “But a modest profit is not good enough for some. They want profits that far exceed what people can afford to pay and that’s the problem.”

Wild points out that Germany’s Constitution guarantees everyone the right to “Wohnraum,” or a place to live. He and others in Berlin reject any suggestion that market forces, such as supply and demand, should influence the price of property or rents.

“An apartment is not just another piece of merchandise that can be rented to the highest bidder like with most other wares,” Wild said. “It’s immobile and can’t be carted off. And it’s not like a stick of butter you could substitute with margarine. There’s no room for speculators when it comes to apartments.”

Ryan Harty, a 34-year-old from Denton, Texas, who moved to Berlin more than a decade ago and now works for Germany’s national association of food banks, joined the resistance march even though his $700-a-month rent has not risen in 10 years and is unlikely to, thanks to rent control. He said he joined the march on behalf of those who can’t afford higher rents.

“Once you move into an apartment in Germany, you are basically in the lease for life unless you cancel it yourself,” said Harty. “I think it’s a good thing that people can feel safe and don’t have to worry about renewing the lease. If you have that long-term security, it’s pretty much the basis for having a life. It’s a lot easier to plan your life.”

Because taking action against “property speculators,” gentrification and developers motivated by profit tends to go down well with most Berliners, some local politicians such as Florian Schmidt of the Greens party have resorted to unusual methods to frustrate and hold off investors.

Schmidt, who is responsible for development in the urban, hip Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district, has been dubbed the “Robin Hood of the property market” because of his ability to use an obscure real estate law to snatch property away from speculators and give the property to state-owned housing companies.

By preventing developers from selling properties for huge profits, he hopes to save 1,000 apartments a year in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg. Critics, though, say he is actually blocking badly needed capital investment to renovate buildings that have fallen into disrepair.

“We want to prevent rental units from being sold off at a profit and turned into privately owned units,” Schmidt said, defending his aggressive tactics. “If someone promises [in writing] not to convert rentals into private apartments, they can buy them. Otherwise, we’re stepping in. Rental apartments need to be protected from speculators. That’s what people are afraid of.”

Kirschbaum is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.