There was no Trump on the ballot, but Irish voters still made their anger clear

Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenny, Fine Gael party leader, attends the vote count for general elections in Castlebar on Saturday.

- Share via

Reporting from Castlebar, Ireland — Voters in Ireland delivered a stinging rebuke to governing parties in elections that reflected concerns that the country’s economic recovery was not being widely felt.

In an echo of the sort of voter anger being heard in the United States this year, anti-establishment parties and independent candidates made significant gains, winning about 25% of the vote combined. Sinn Fein, the democratic socialist party that is linked to the Irish Republican Army, won 14% of the vote, making it the country’s third largest party.

A center-right coalition led by Prime Minister Enda Kenny will not retain power after seeing its share of the vote fall from 56% in 2011 elections to around 32% in voting Friday, with several seats still to be counted Monday. With no party or alliance close to winning enough seats to form a government, it is unclear who will lead Ireland’s next government.

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

Several government ministers lost their parliamentary seats in the vote, although the prime minister held on. Speaking to media after retaining his seat, Kenny said, “Democracy is exciting, but merciless when it kicks in.”

Whether Kenny can remain as prime minister or even leader of his Fine Gael party is uncertain.

Kenny presided over an economy that substantially rebounded after being hit hard by the global banking and real estate collapse in 2008, and enduring several years of austerity measures imposed to meet the terms of a roughly $90-billion international bailout.

Fianna Fail party officials read the morning newspapers as they wait outside the count center in Dublin, Ireland, on Sunday.

And though Ireland’s economic growth outpaced the other 27 member states of the European Union in 2015, many voters believed that the benefits of that revival were not being widely felt and that Kenny’s campaign slogan — “Let’s keep the recovery going” — was premature, sharpening anger over issues such as a poorly run health service and a government plan to impose water charges.

Jason Hennigan, a voter in Kenny’s constituency, said he kept his landscape gardening business going despite the collapse of Ireland’s construction industry in 2008. But he said that the current government did not provide enough assurances to self-employed business owners in tough times.

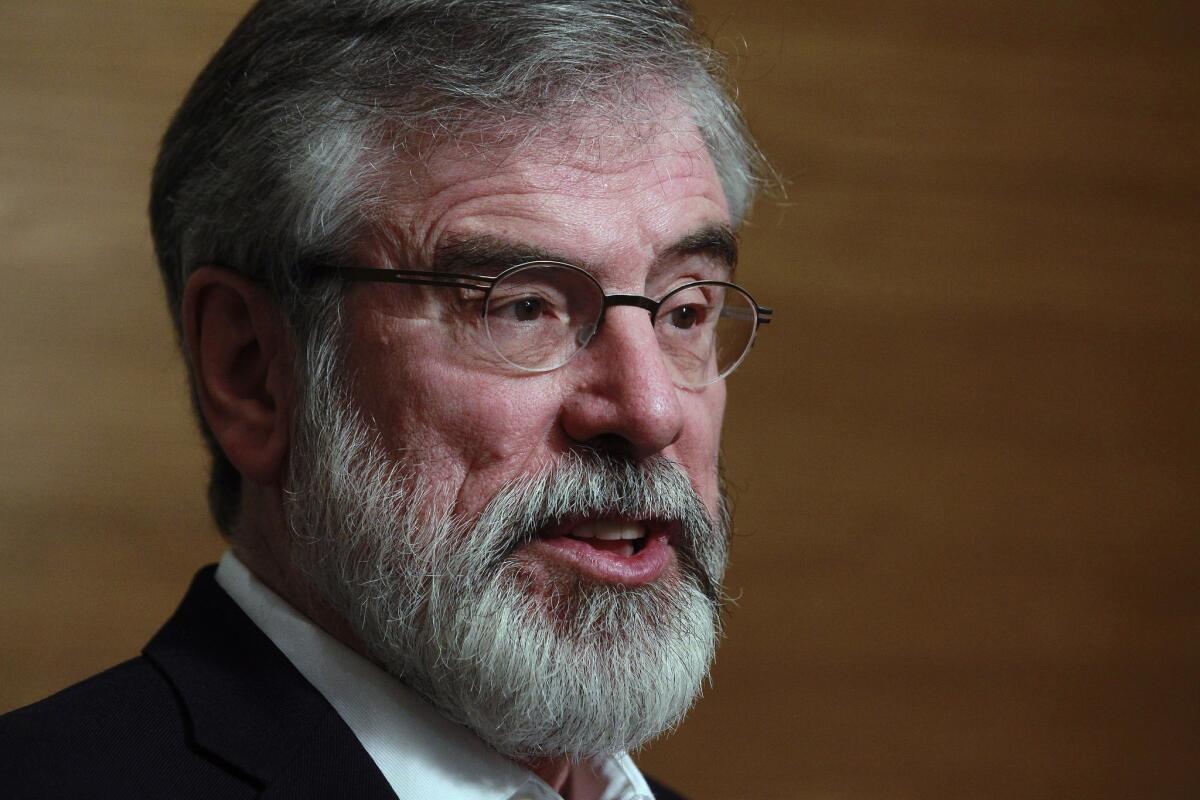

Sinn Fein party leader Gerry Adams talks to members of the media in Dundalk, Ireland, on Sunday.

“If I got hurt or anything, there’s no support there,” he said.

The new Parliament convenes March 10, and the period before and after will be dominated by deal making. However there is no indication yet that any combination of parties will agree to govern together, raising the prospect of another election later this year.

Going by the seat numbers, the most likely government would be a coalition between Kenny’s Fine Gael and another center-right party, Fianna Fail — historically the two biggest parties in a country that has never had a left-leaning government. Fianna Fail recovered some of the support it lost in 2011, when it was widely reviled for its role in the 2008 crash.

But by Sunday, leading figures in both parties were saying contradictory things about forming such a coalition, casting doubt on whether it could happen.

The two parties share some ideology but have long seen each other as rivals. The temptation of power could dilute those animosities, especially given the gains for independent candidates and left-wing nationalist groups such as Sinn Fein.

Sinn Fein was long the political sibling of the IRA, which wage a three-decade bombing campaign to try to end British rule in Northern Ireland. Since a 1998 peace deal, Sinn Fein has made incremental gains in the independent Republic of Ireland and will lead the opposition if the two center-right parties form a governing coalition.

While meeting farmers in Castlerea, a town in the west of Ireland, Michael Fitzmaurice, one of the winning independent candidates, cited lingering resentment in his area about the Kenny government reversing a promise to retain emergency services at a nearby hospital.

“There is a small pickup,” Fitzmaurice said of the economic recovery on which the Kenny government campaigned, “but there is a long way to go for many parts of the country.”

Roughneen is a special correspondent.

ALSO

What a Donald Trump presidency might actually look like

Breaches reported in Syrian cease-fire, but it’s mostly holding

Reformers and moderates romp in Tehran as Iran election gauges popularity of nuclear deal

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.