Holy wars: The Catholic Church’s long history of bickering

- Share via

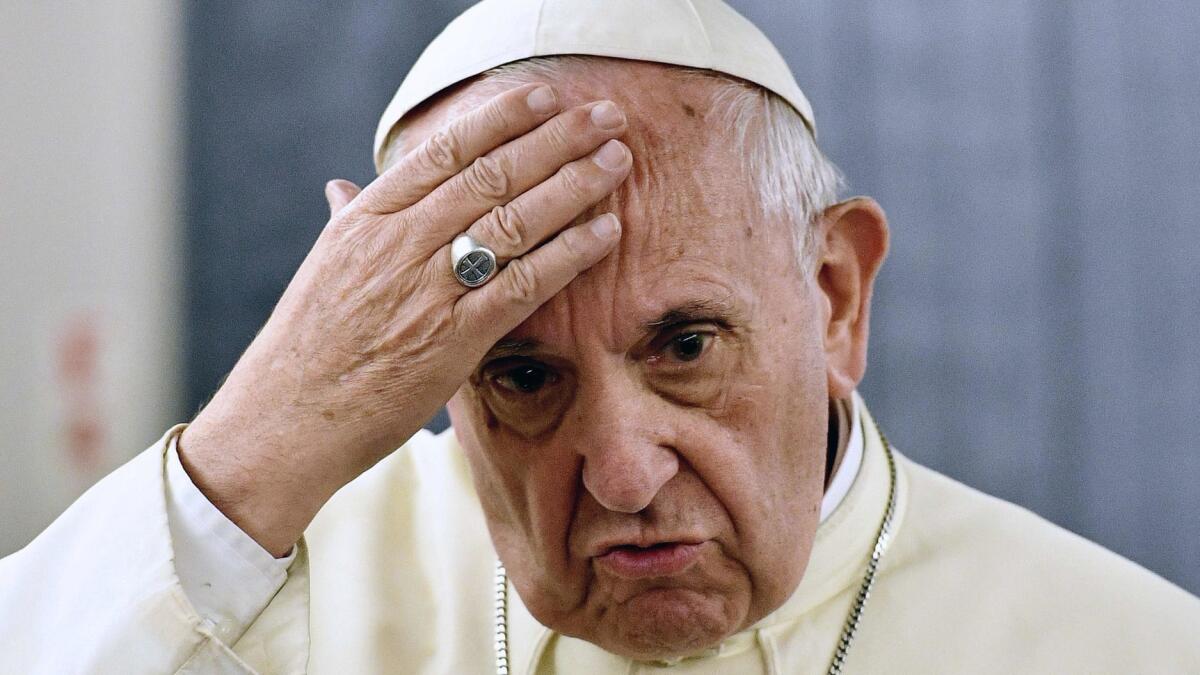

Reporting from Rome — After years of receiving plaudits for his upbeat, merciful brand of Roman Catholicism, Pope Francis has seen his popularity slip in the U.S. over accusations he has fumbled the church’s attempt to stamp out child sex abuse.

Even as fresh revelations of priestly predators emerge in Pennsylvania, Germany and Chile, Francis has been accused by a senior archbishop, Carlo Maria Vigano, of covering up the alleged abuse of young seminarians by former Washington, D.C., Archbishop Theodore McCarrick.

Francis was already facing intense criticism from a well-funded community of conservative Catholics, many of them in the U.S., who loathed the pope’s liberal views and his move to allow remarried divorcees to take Communion.

Some of these same critics, despite a dearth of scientific evidence connecting homosexuality to child molestation, believe it is to blame for the level of child sex abuse in the church and fault Francis for his tolerant attitude toward homosexuality. It was the Argentine pope, they note, who said, when asked about gays and lesbians, “Who am I to judge?”

While the ongoing infighting between the pope and his detractors may be intensifying, a look at Catholic history suggests it has nothing on some of the rows that have split the church in the past.

1054 | The East-West Schism

As schisms go, this one is hard to beat — since it was about 600 years in the making, led to the creation of the Orthodox Church and has not been patched up nearly 1,000 years after it shook Catholicism.

In the 4th century, after the Roman Empire had adopted Christianity as its official religion, the empire split, with the creation of an Eastern empire run from Constantinople — modern-day Istanbul in Turkey — and a Western empire based in Rome.

In the wake of this political split, church leaders drifted apart, setting the scene for centuries of bitter rows, often over jurisdiction between the Latin-speaking leadership in Rome and the Greek-speaking leadership in Constantinople.

Frictions were also manifested in battles over theology: The Eastern church objected to Rome’s use of unleavened bread and its depiction of Christ as a lamb; Rome, for its part, insisted on its priests being celibate, while the East permitted married priests.

Matters came to a head in 1054 with a formal split amid a flurry of mutual excommunications, setting up centuries of continued tension, not helped by the sack of Constantinople in 1204 by Catholic Crusaders, who made off with precious relics.

Orthodox churches began to proliferate in the East, spreading to Russia, where today two-thirds of the world’s 200-million-plus Orthodox Christians live.

The Vatican now gets along with the patriarch of all the Orthodox churches, but it was not until 2016 that Rome and the Russian Orthodox Church overcame centuries of distrust and their two leaders — Pope Francis and Patriarch Kirill — held a historic first meeting.

1378 | The reign of the antipopes

In the 14th century, clashes between Catholic Church leaders resulted in the election at one point of competing antipopes in France and Italy.

The so-called Western Schism got underway when a group of cardinals objected to the election of Pope Urban VI in 1378 and elected the first of a series of antipopes based in Avignon, France, who claimed Catholics should obey them, not the pope in Rome.

In 1409, the Council of Pisa in Italy, which included cardinals and bishops, sought to depose the pope in Rome and the French antipope but instead added to the confusion by electing its own pontiff, Alexander V, meaning the world briefly had three competing pontiffs, before the church again unified behind one Rome-based pope in 1417.

1517 | The Reformation

By the 16th century, the power of the Catholic Church in northern Europe was being questioned by an increasingly literate and free-thinking middle class, and on Oct. 31, 1517, a then-unknown theologian, Martin Luther, kick-started the Protestant Reformation with a defiant challenge to Rome.

That day he is said to have posted his 95 Theses on a church door in Wittenburg, Germany, challenging church practices. Four years later Luther was excommunicated, but the advent of printing presses ensured his work was widely read — and the Protestant split from Rome was underway.

In his tracks came French theologian John Calvin, whose disciples — Calvinist missionaries — helped spread the new faith, while a smaller sect, Anabaptists, later evolved into Mennonites in the U.S.

In Scotland, meanwhile, Presbyterianism took root, and by the middle of the 16th century Catholicism was on its back foot across northern Europe.

1534 | The English Reformation

England’s split with Rome was spurred by King Henry VIII, who wanted to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon when she could not give him a male heir, and was incensed when Pope Clement VII refused to grant the annulment.

Shrugging off papal authority, Henry established the Anglican Church in 1534, putting himself at the head so he could handle his own marriages. He also oversaw the closing of monasteries in England.

Officials justified the eviction of monks by citing their alleged storing of fake relics. In seizing and selling their land, the English Crown enjoyed a huge windfall.

Those who viewed the Church of England’s version of Protestantism as too close to Catholicism, including so-called Puritans, set off for America to establish the colony of Massachusetts, which would become one of the original United States, where they could practice their faith.

Kington is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.