India’s Narendra Modi, battling for reelection, gets a questionable Bollywood boost

- Share via

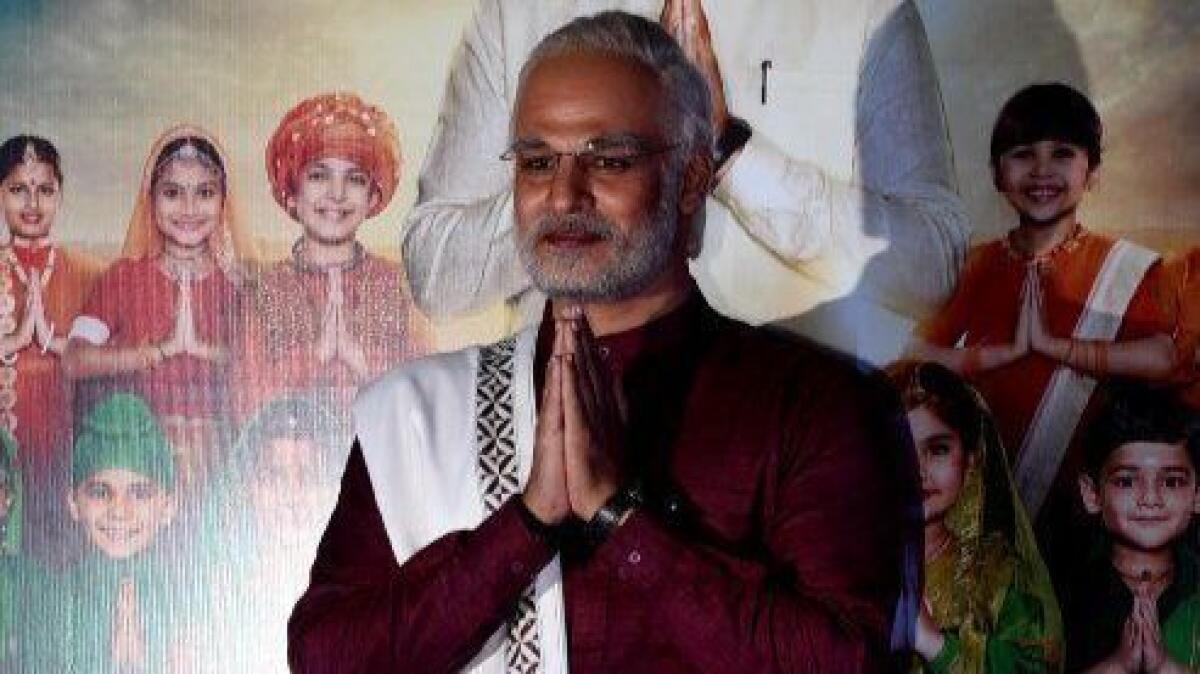

Reporting from New Delhi — In a new Bollywood epic, the hero leaves home as a young man to assume an ascetic life in the wilderness. He brandishes a giant Indian flag in the midst of a gun battle, yelling patriotic slogans as bullets fly around him, and later appears to carry a child to safety amid deadly riots.

The identity of this intrepid action star? Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

A flattering but factually questionable biopic of the Indian leader was set to hit theaters this week — just days before voting begins in a weeks-long general election in which Modi is battling for a second term.

But after two weeks of controversy during which critics slammed the film — “PM Narendra Modi: Story of a Billion People” — as political propaganda with the primary intent of influencing the vote, its release has been delayed.

“This is to confirm, our film ‘PM Narendra Modi’ is not releasing on 5th April,” producer Sandip Ssingh tweeted Thursday. “Will update soon.”

The postponement came after Modi’s chief rival, the opposition Congress Party, urged India’s Election Commission to block the film’s release, saying its purpose is to “get some extra mileage in the elections.” There are concerns that its release would violate government guidelines that prohibit the use of mass media to bolster the ruling party’s political campaign in the run-up to voting.

The Election Commission has not made a clear ruling, but Indian news media reported Thursday that India’s Supreme Court would hear the opposition’s complaint next week.

Last month, two airlines and the national railways had to withdraw boarding passes that featured Modi’s picture. And electoral officials reprimanded two newspapers for running full-page ads for the biopic.

But another Indian government body that oversees movie releases reportedly had no problem with the film hitting the big screen during the election.

India’s Central Board of Film Certification, known as the censor board, often restricts content it deems sensitive, banning almost 800 films from 2000 to 2016 for a variety of reasons including politics, sex and violence. But the Modi biopic is part of a recent wave of political films amplifying pro-government sentiment that earned the board’s approval.

The new film’s trailer, with its overheated scenes of a valiant Modi, has been viewed more than 20 million times since March 20, delighting the prime minister’s partisans. Modi’s personal popularity drove his Bharatiya Janata Party to power in 2014, and five years later his appeal is still high and his presence wide — it’s hard to go anywhere in India without seeing his face on billboards, newspaper ads and television screens.

“This movie will be a large-screen version of what Modi has been doing on TV,” said Shubhra Gupta, a film critic and columnist for the Indian Express newspaper. “I imagine it will be 360 degrees, playing in practically every theater around.…

“The movie will give him much more visibility — as if he needed any more.”

Although there have been no advance screenings of the film, the trailer suggests it will reinforce themes frequently cited by Modi’s supporters: The 68-year-old is singularly focused on serving the nation, a strong leader who gets things done and a man who overcame humble beginnings and the disdain of elites to become prime minister.

Many say this image is exaggerated and that the movie takes liberties with the facts.

“From what I’ve seen, it paints a larger-than-life picture of Modi that’s distorted to project an image that’s far away from the truth,” says Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, the author of an authoritative 2013 biography of Modi.

“It’s making him into some sort of superhuman with divine powers, or somebody whose heart bleeds for the downtrodden and victims of various forms of violence. … But his actions in the last five years as prime minister show he’s normally the last one to speak on such issues.”

The trailer’s depiction of the 2002 religious riots in Gujarat, a state Modi then led, is particularly controversial. At least 1,000 people, mostly Muslim, were killed in the violence. Some accuse Modi — a longtime Hindu nationalist — of not doing enough to stop the bloodshed.

From the archives: Indian Muslims wary of man poised to take reins »

Modi has never been charged in connection with the violence. But in scenes featured in the trailer, Modi is seen looking helpless and despondent as the riots unfold, at one point lamenting emotionally, “My Gujarat is burning!”

Amid this chaos, the scene appears of him carrying a child, evidently to safety.

“Nothing like this ever happened,” Mukhopadhyay said.

“He was comfortably in his chief minister’s office and bungalow. He didn’t act as promptly as he should have. He allowed the situation to escalate.”

Mukhopadhyay also said there was no evidence that some other scenes in the trailer actually occurred, such as Modi being caught in the middle of a gun battle involving security forces.

Those behind the film deny it is propaganda.

“Because it’s coming out at this point of time, people are talking like that,” Omung Kumar, the movie’s director, told reporters last week. Asked whether he should delay the release, he said: “Why should I? The film is ready. Had it not been ready, it would have been a different story.”

A former chief election commissioner of India, N. Gopalaswami, said in an interview that he believed the timing of its release was the only issue — not the allegations of embellishments and inaccuracies.

“Nobody can put a restriction on human imagination,” he said.

Other films that passed muster with the censor board included a September blockbuster that glorified a 2016 Indian counterattack on a militant camp in Pakistan that the Modi government called a “surgical strike.”

And in January, a film about Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh portrayed Singh’s Congress-led government in an unflattering light. Critic Uday Bhatia blasted it as “an unsubtle hit job” and “a political ad.” Cast as Singh was veteran actor Anupam Kher, who once said he had no problem being called Modi’s chamcha, or stooge.

Many other Bollywood actors have openly praised Modi, including Vivek Oberoi, who played him in the biopic and campaigned for him in 2014.

In January, after the prime minister held a meeting with more than a dozen Bollywood stars, reportedly to discuss “nation building,” the group took a selfie that garnered more than 2.6 million likes on Instagram.

To a large degree, Bollywood and the censor board — whose members are appointed by the government in power — tend to follow the prevailing political trends. India’s film stars, the biggest of whom are revered almost as demigods, rarely weigh in on controversial issues.

In 2015, when Bollywood megastar Aamir Khan, who is Muslim, said he was alarmed at what he perceived to be growing religious intolerance under Modi’s watch, there were widespread calls to boycott Khan’s films.

Few others have dared to make the same mistake.

“Bollywood people feel Modi is here to stay,” Mukhopadhyay said, “and they want to be on the right side of him.”

Directors and producers are also reluctant to criticize elected officials, especially popular ones such as Modi, fearing retaliation from the censor board.

“You cannot make a film in this country without the state,” said Gupta, the columnist, who was a censor board member under the Singh government.

“Funding can come from anywhere. But if you want to get your film out into theaters, you will only get certification” through the censor board, she said. “It’s the final bastion.”

Gupta acknowledged that when the Congress Party was in power, it also used the board to its political advantage. Still, she called the recent trends unprecedented.

“It’s never happened that in the run-up to elections so many films have come out one after the other [where] the optics are clearly all in favor of the ruling party,” she said. “This has ratcheted things up to a level we haven’t seen before.”

Malhotra is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.