South Koreans blame politics in Roh’s death

- Share via

Reporting from Bongha, South Korea — They came bearing flowers and cigarettes for their fallen hero, the former head of state whose life many believe was cut short by the vengeful nature of South Korean politics.

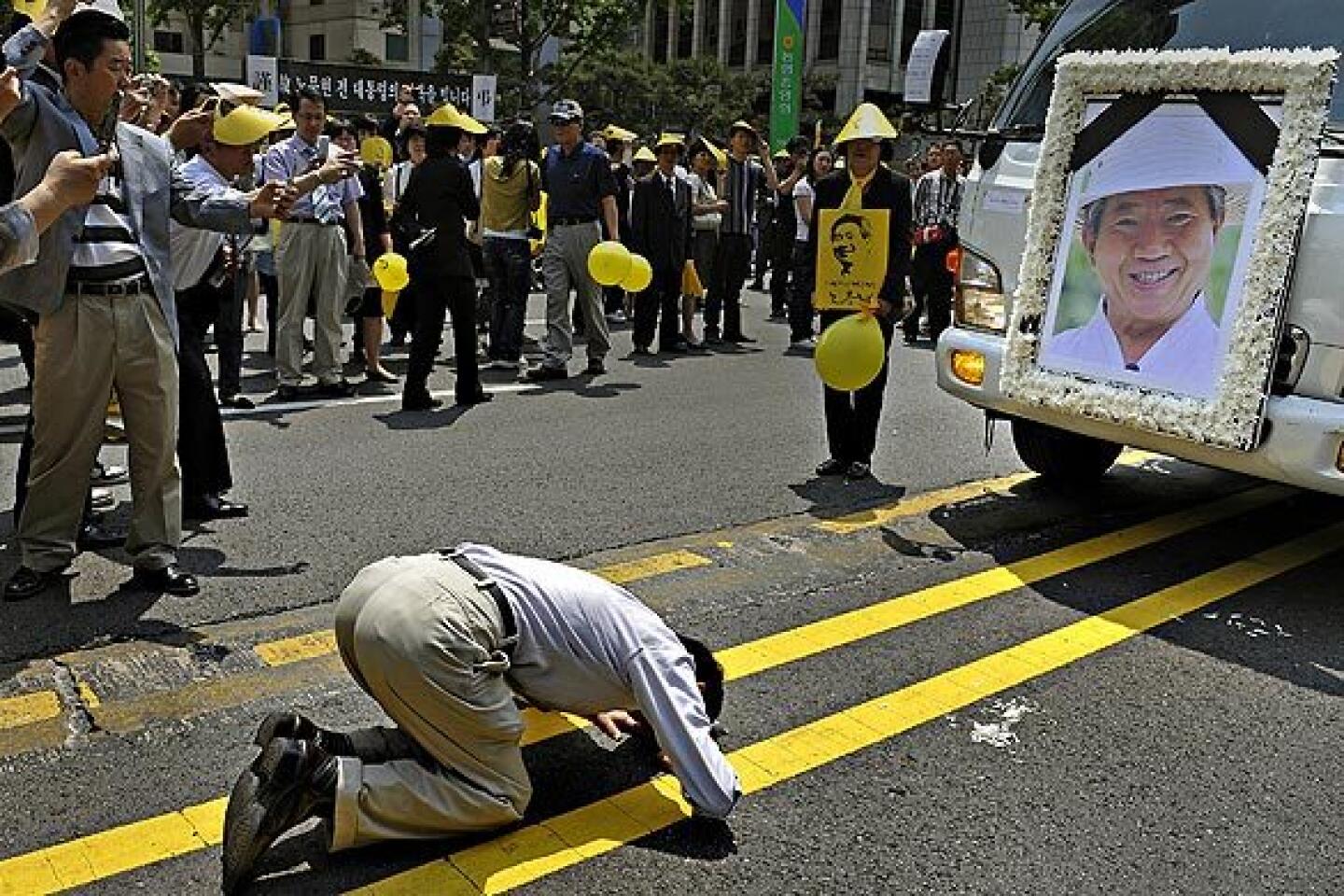

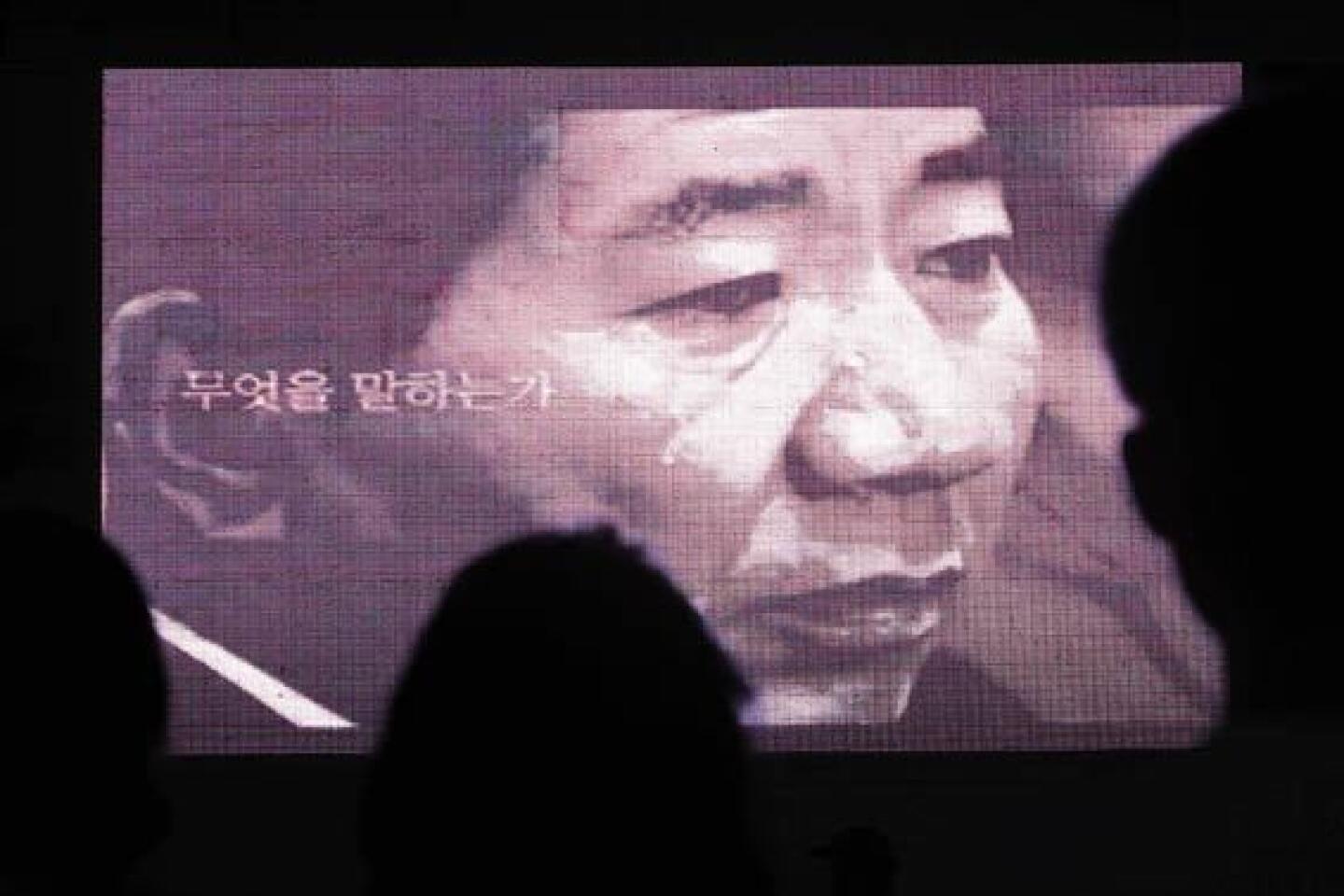

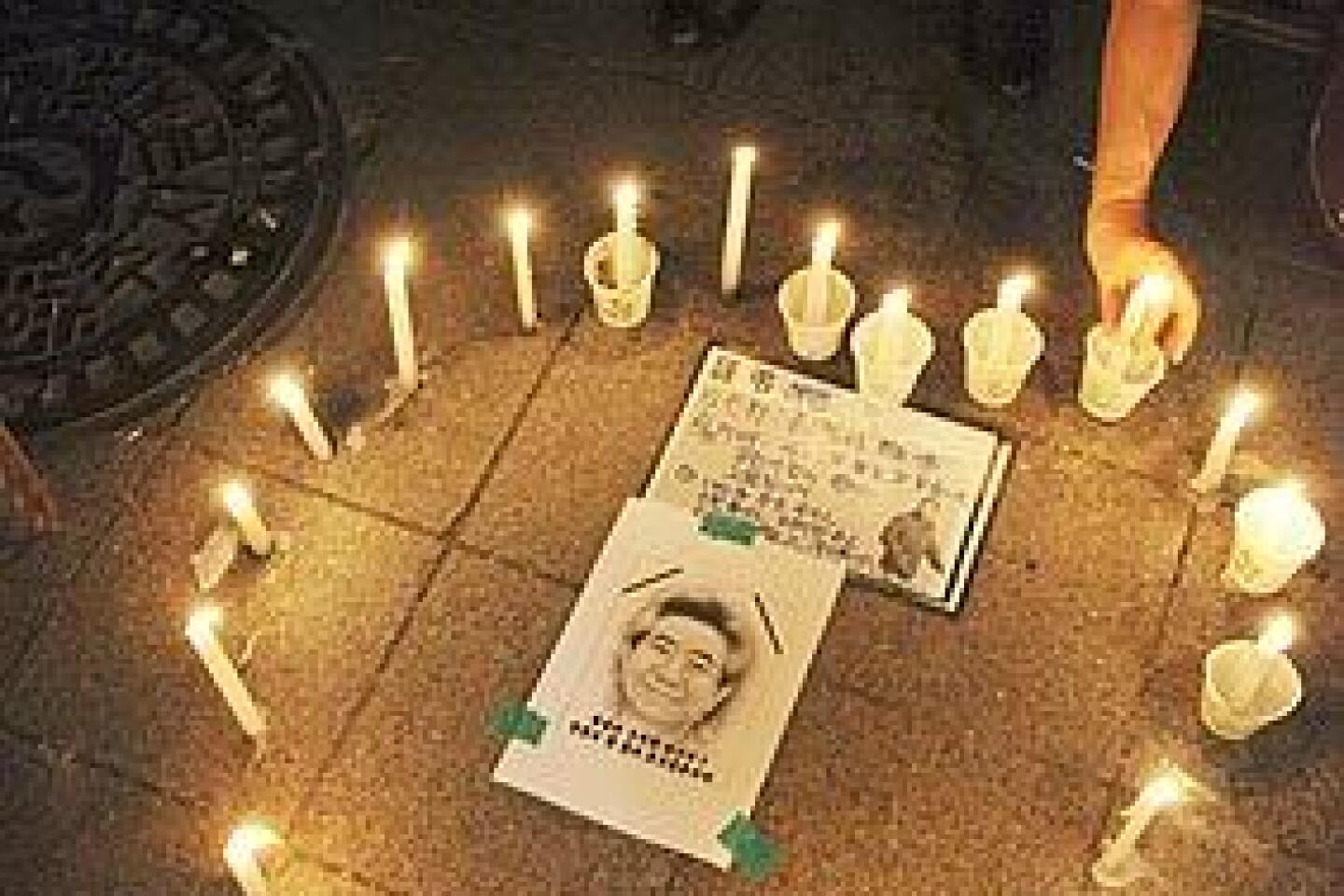

Countless mourners have paid their respects to Roh Moo-hyun, an outpouring of grief for the ex-president who jumped to his death last week amid a public circus over an inquiry into whether he accepted $6 million in bribes during his term in office.

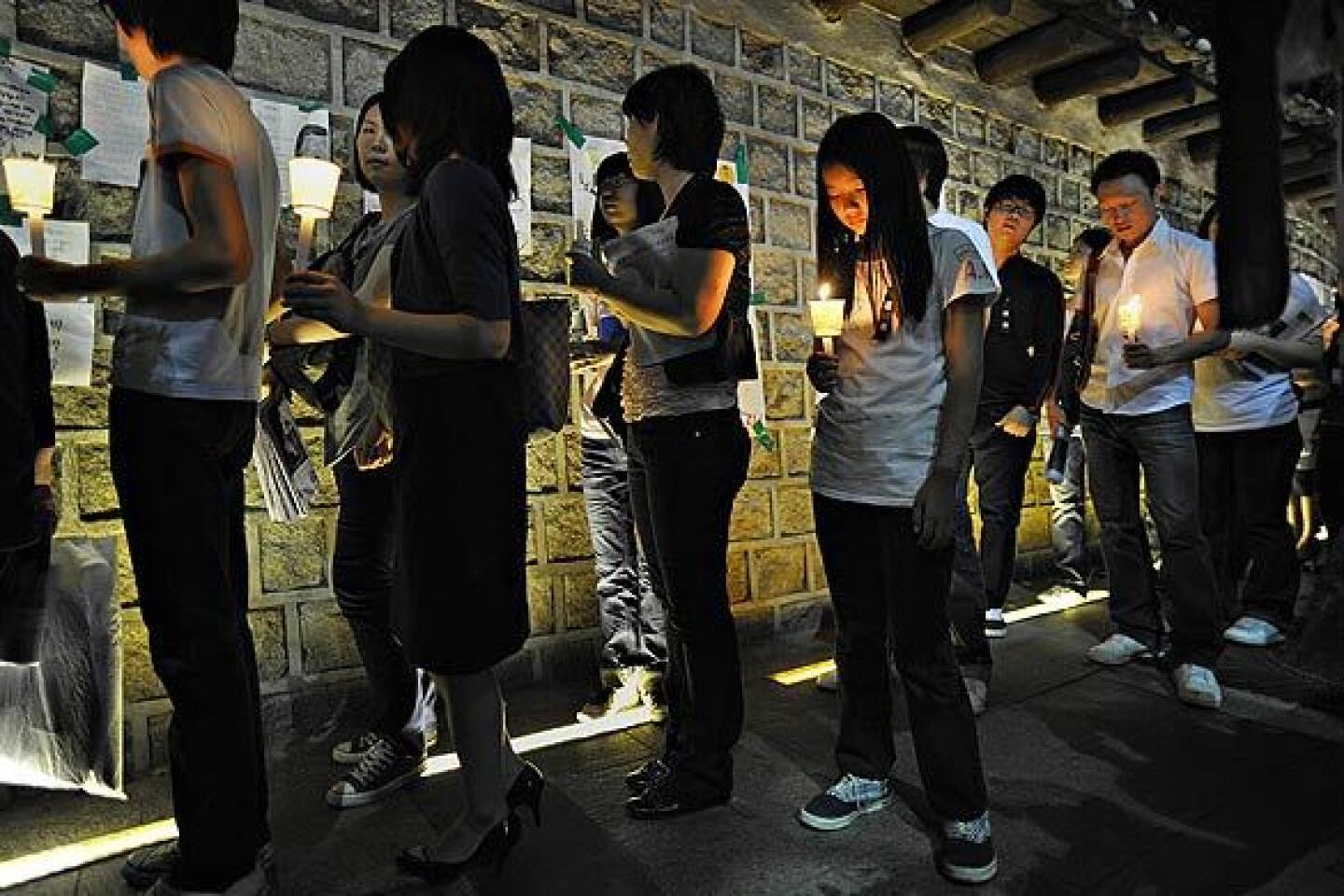

Dozens of memorial sites have sprung up across the country. In Seoul, tens of thousands of mourners flooded a central plaza this morning to watch a televised memorial service for Roh outside the nearby Gyeongbak Palace, where his body was being brought.

Perhaps no place, however, embodies the political tensions that remain better than Bongha, the tiny enclave of a few dozen homes where the ex-president was raised -- and where he died.

A million mourners packed into the community, which is dotted by rice fields and light industry warehouses. Round the clock they have come, bowing humbly and wiping away tears, placing chrysanthemums beneath a portrait of the 62-year-old Roh.

In South Korea, incoming administrations typically savage those who preceded them. Many of Roh’s supporters talk of a smear campaign -- news media leaks by prosecutors and a vendetta by the Lee Myung-bak administration.

“It’s a political murder,” said Sohn Dae-jeong, 40, who had arrived at Bongha after a five-hour overnight bus trip from Seoul. “The administration, the conservative newspapers, the prosecutors, they killed him. I hope they are happy now.”

Roh entered the national scene with a run for president in 2002. He represented a hope for change that supporters compare to the message invoked by Barack Obama.

A poor farm boy who never attended college, Roh nonetheless passed the bar exam and went on to become a judge and civil rights lawyer. He campaigned to wrest control of South Korea from the wealthy and pledged to clean up the endemic political corruption.

But critics say Roh turned out to be just another politician who professed an ethical code to which he did not adhere.

Whether or not he was guilty, many have already forgiven Roh, rationalizing that even if he did take payoffs, they were far less than those accepted by other high-level politicians.

“I don’t call these bribes,” said Kim Myoung-guk, an inn owner. “They’re political patronage. Everyone takes them.”

Even in thick-skinned political circles, Roh’s suicide has led to soul searching.

The prosecutor in the case offered to resign and President Lee has resisted visiting Bongha, the epicenter of Roh’s support, citing security concerns.

Many say Lee is not welcome here.

“I don’t think the president is qualified to come here,” said Sohn Yong-min, 40, a teacher from Seoul. “This administration set out to murder Roh in public. Now that he’s dead, Lee won’t come. He’s not wanted here anyway.”

All week, the long lines of mourners resembled a grim pilgrimage. Along a country road that leads to Roh’s home, there were men in suits, groups of bald monks in flowing robes and elderly people using canes and walkers.

They passed thousands of hand-scribbled banners, including one strung across a copse of pine trees that read: “I’m sorry for not being able to protect you.”

Others, apparently written by children, were heartbreaking. “I like your smile,” read one. “Don’t do politics in heaven.”

Not far from Roh’s memorial, just across a fallow rice field, sits the imposing boulder called Owl Rock, from which the ex-president jumped to his death Saturday during an early-morning walk.

Some mourners sat in front of the promontory and wept, using binoculars for a better view of the scraggly cliff where Roh and a bodyguard stood before 7 a.m. that day.

Roh asked his minder for a cigarette and then sent him off on an errand before he jumped.

Thousands of mourners offered up cigarettes as a gesture to Roh, who had quit smoking, only to restart under pressure of the investigation, aides say.

“People take one puff of the cigarette and then lay it down at the memorial,” said Kim, the inn owner. “It’s a last moment with a man we will always consider one of us.”

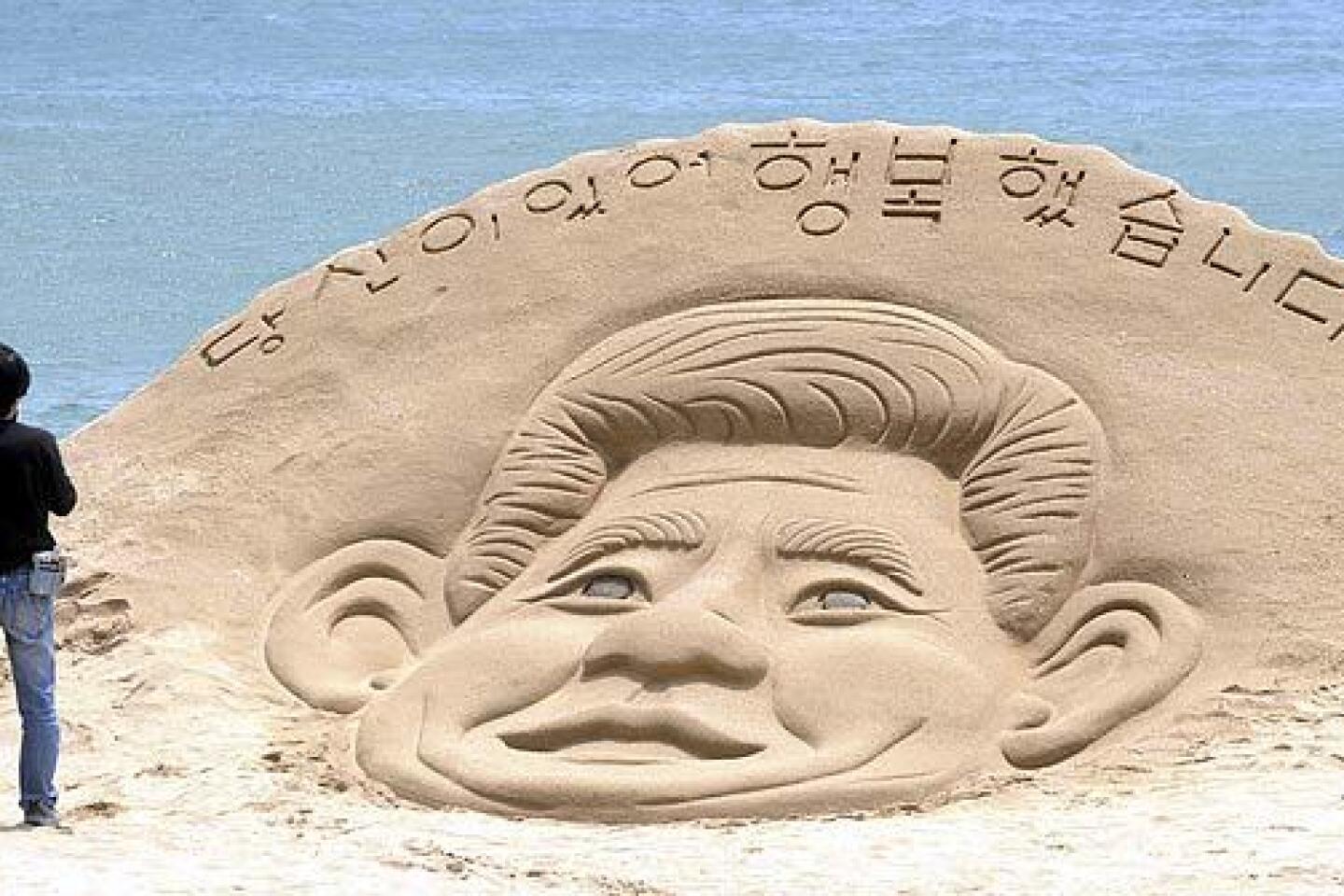

Indeed, with his ruddy face and direct gaze, Roh often appeared more like a blue-collar worker than a sitting president.

When he left office in early 2008, residents here doubted that Roh would return to the community where both he and his wife were raised. About 250 miles southwest of Seoul, it’s a decidedly middle-class area that many felt was not fit for such a celebrity.

But he built a compound at the end of a narrow road. Residents often saw him riding his bike or taking walks, two bodyguards usually in tow.

To them, Roh was approachable, not brusque or imperious. He raised ducks and played with his grandchildren, often wearing a wide-brimmed hat, like most farmers here.

Roh spent hours discussing proper techniques for growing rice, the local staple.

“He didn’t make a lot of jokes,” said Cho Yong-hyo, a former Bongha village leader. “But he really loved to talk freely to anyone he met, as if they were his family member or sibling. He usually asked us what made it hard for us to farm.”

As the investigation closed in, Roh stopped eating. In the days before his death, he no longer answered e-mails or greeted supporters and neighbors.

In June, villagers will congregate in an expanse of community fields for the seasonal rice planting. As he watched the long line of mourners pass, businessman Park Moo-sik said it was only now dawning on him that Roh wouldn’t be there among them.

“He would have been working right along with us in those fields over there,” Park said, his voice catching.

“I miss him already.”

Ju-min Park of The Times’ Seoul Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.