Sumo wrestler has put tradition on its ear

- Share via

TOKYO — At a mere 308 pounds, Asashoryu is not the biggest of the big-bellied men waddling around the dirt ring of this chilly sumo training stable, looking for someone to slam up against.

But he is definitely the baddest.

His opponents look like they were carved from mountains. But Asashoryu cuffs them in the ear and drops them to their knees. He drives his palm into their throats and they recoil. He picks them up by their belts and flings them, their legs flailing, out of the ring.

He toys with fellow wrestlers like a cat playing with a beach ball.

Asashoryu’s cream-colored, almost unblemished body is now the sun around which Japan’s national sport revolves. Just 24 and still a bit baby-faced, he has won six of the last seven major tournaments since 2003, dominating sumo the way Tiger Woods once did golf.

He is sumo’s only reigning yokozuna, top-ranked in a sport that never has more than four yokozuna at a time, a wrestler many call the best Japan has seen in the postwar era.

And he isn’t even Japanese.

Asashoryu’s real name is Dolgorsuren Dagvadorj, and he is Mongolian. Born into a family of wrestlers in the Central Asian country’s capital, Ulan Bator, he came to Japan after high school nearly eight years ago, a strong kid with a mean streak and dreams of sumo stardom. He adopted the name Asashoryu, which means Blue Dragon of the Morning, just as a wave of foreigners began shattering the cultural barrier that had long made sumo the most Japanese of sports.

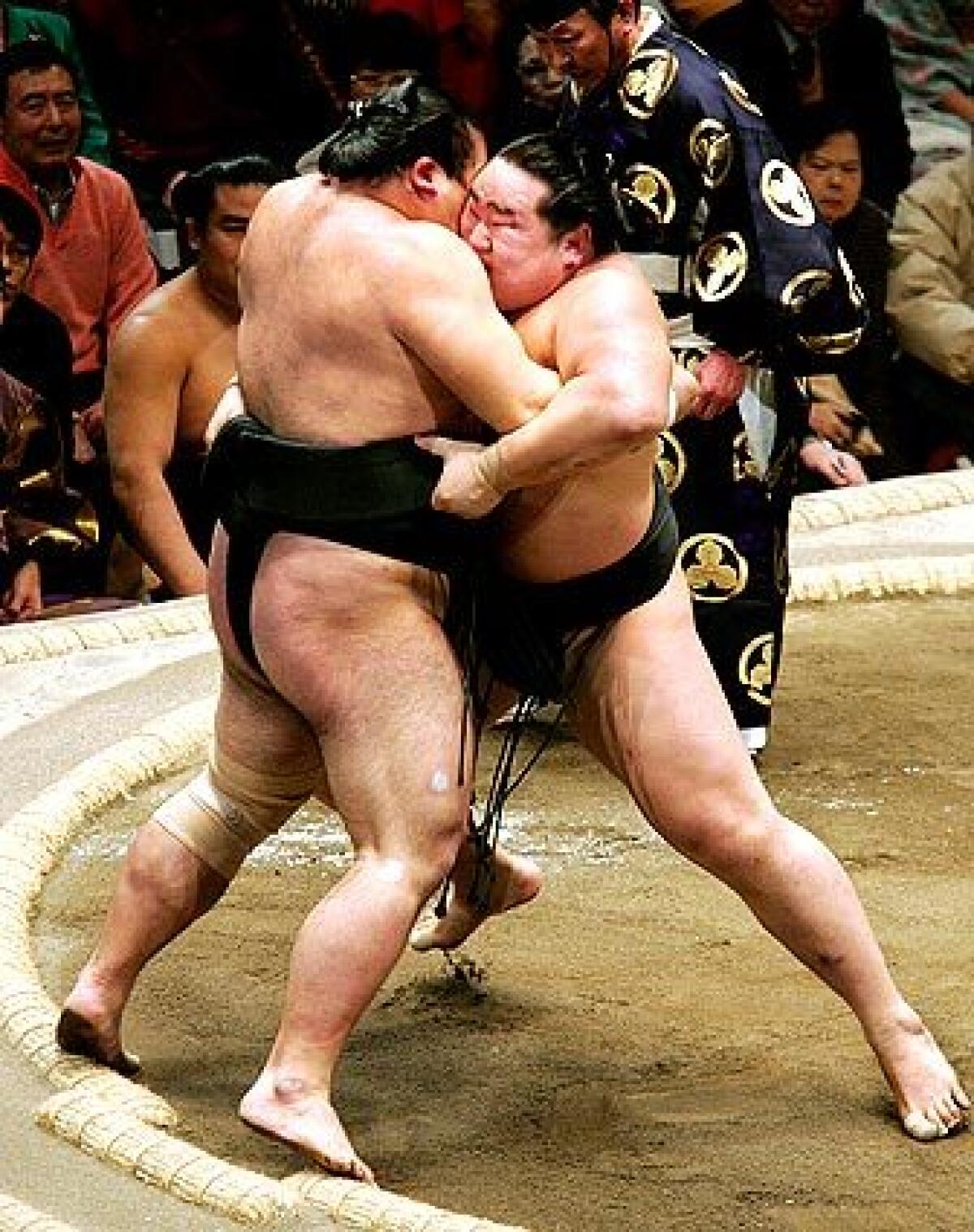

The foreign invasion is revolutionizing sumo, a sport where massive men collide in a short explosion of violence that ends when one of them is thrown from the ring or touches the ground with any part of his body other than his feet.

Sumo may have had its ups and downs over its 1,500 years of recorded competition, but they have almost always been Japanese ups and downs. Legend has it that Japanese supremacy on its islands was established through a bout between gods, and the sport’s rituals provide links to Japan’s religious and militarist roots.

Now with its top ranks increasingly filled with wrestlers, or rikishi, from other countries, sumo finds itself adrift. Attendance is flagging. There is no obvious Japanese wrestler emerging to capture fans’ hearts and challenge the Mongolian’s hold.

“The Japanese are no good,” Asashoryu says derisively, morning practice over. He sits down cross-legged to lunch -- a big lunch -- on a tatami carpet.

“Japan’s economy developed and the people became weaker,” he says, elaborating by twitching his thumbs to simulate the sedentary habit of playing electronic games.

Asashoryu laughs, and he is joined by good-spirited nodding from even the Japanese wrestlers around the table. (The yokozuna is accustomed to having people laugh at his jokes.) By contrast, he says, his summers spent on the steppes of Mongolia, sleeping in a tent, herding sheep and riding horses, were just the stuff for nurturing the toughness sumo requires.

“The sumo world is a hard life,” he says, as other wrestlers dutifully replenish his plates of spaghetti and pork, tofu and rice (three bowls), an omelet and bottomless cups of tea.

Wrestlers must not only win tournaments to qualify as a yokozuna but must be accepted by sumo’s governors as being a man of exemplary character. The emphasis on cultural ritual and comportment means the sport has arguably more in common with a tea ceremony than baseball. A yokozuna not only performs a ceremonial role of chasing evil spirits from the ring before a fight but is also the master to an entourage of other rikishi.

Asashoryu is not sumo’s first foreign yokozuna. In 1992, 525-pound Hawaiian-born Chad Rowan, who fought under the name Akebono, became the first wrestler from outside Japan to attain the status. Akebono’s accomplishment was matched by a Samoan-Hawaiian of similar weight named Musashimaru, known to his family as Fiamalu Penitani, who became the second foreign yokozuna in 1999.

But the first foreigners were outsiders, renegades who scaled the walls as solo acts largely on the basis of their overwhelming size. By contrast, the current erosion of Japanese dominance has marked a revolution within the sport that began in the late 1990s. Faced with a sharp decline in the number of Japanese teenagers choosing to dedicate themselves to the rigid sumo lifestyle, the sport’s stable masters, or club owners, sent scouts across Asia and Europe in search of new talent.

Hundreds of aspiring rikishi came to Japan to see whether their raw skill and strength could earn them a place in the world’s only professional sumo circuit. For a sport with an increasingly global complexion, there is still only one place to perform: the birthplace and spiritual home of sumo. There are now 61 foreign rikishi in Japan among the more than 700 ranked wrestlers, including 37 Mongolians.

Sumo’s current cast hails from places that include Russia, Bulgaria, China, Estonia, Tonga and Brazil. Almost one in three places in the top division is occupied by a foreign wrestler. If there is anyone who threatens Asashoryu’s dominance it is Hakuho, another Mongolian, who at 19 has already become a crowd favorite in Japan.

Fans of sumo in Mongolia clamor for news of their countrymen’s success. But Japanese supporters are peeling away from sumo for more fashionable sports such as soccer, or hybrid forms of combat entertainment such as K-1, an extreme-fighting carnival that melds martial arts with street brawling. K-1 has even lured Akebono out of retirement and back into the ring (he has lost miserably in each of his six fights), and has recruited one of Asashoryu’s brothers, Sumiyabazar, to move to Japan and fight under the name Blue Wolf.

Meanwhile, the recently concluded New Year Grand Sumo Tournament, won again by Asashoryu, who went undefeated in 15 bouts, played to half-empty halls in Tokyo. Sumo magazine publishers say their circulation is half of what it was 10 years ago. Given those woes, you’d think the Japanese would be grateful for Asashoryu, whose success is a reminder that sumo is about technique, not just bulk. But Asashoryu has had a harder time winning Japanese hearts than his fights.

The Japanese have traditionally expected their yokozunas to show about as much emotion as a Noh theatrical mask -- in other words, none. Champions are supposed to possess hinkaku: a sense of dignity and grace. That is why there is much muttering about Asashoryu’s very un-Japanese exuberance in the ring and his tendency to get into trouble outside it.

The purists don’t take kindly to his fist-pumping victory celebrations, or the way he glares at referees, or how he ends fights with an extra shove for emphasis to opponents already out of the ring. They resent that he uses his left hand instead of the traditional right when he throws salt into the dohyo, the ring, for the ritualized purification before a fight.

And they point to a series of incidents that has led some sumo fans and officials to openly question whether Asashoryu should be stripped of his yokozuna status. (Yokozunas are never demoted. If their ability starts to fade, they are expected to retire.)

There was his notorious disqualification in 2003 from a match for pulling the top knot -- the carefully combed and pinned hair -- of fellow Mongolian Kyokushuzan. Three days later, Asashoryu and Kyokushuzan resumed their argument when they began brawling at a bathhouse where they had been soaking together.

Then police had to be called to Asashoryu’s training stable last summer when neighbors reported hearing late-night drunken shouts and threats between the wrestler and his stable master -- roughly the equivalent of Kobe Bryant taking it into the alley with Jerry Buss. Newspapers reported that fellow wrestlers had to hold Asashoryu back after the two men started scrapping over the division of spoils from the sale of media rights to the yokozuna’s wedding.

Finally, Asashoryu’s status as a foreigner received unwanted extra attention last fall when three of his Mongolian relatives who had come to Japan for his wedding stayed on afterward and found factory jobs without getting work permits. They were deported after being swept up in a police raid.

The Japanese press has feasted on such Asashoryu scandals. They nicknamed him “Genghis Khan” and “The Bully from Bator.”

“Of course the media make a fuss about me,” Asashoryu says, waving his troubles away. “It would be the same in America if a foreigner came in and became champion of one of your national sports.

“But the Japanese people are very generous. In the fighting world, it is important to show you are trying hard. I know if I try hard, the Japanese will accept me.”

Desire is not something Asashoryu lacks. Growing up in a family where his father and two older brothers were amateur wrestlers -- his eldest brother carried the Mongolian flag into the opening ceremonies of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta -- he was forced to struggle from an early age.

“I was the baby,” Asashoryu says. “We were poor, and my father was a strong figure; it was my dream to be like him. My older brother is 100 times stronger than I am. So I’ve always been very, very competitive.”

So competitive that he scowls when he first sees the new 10-inch Asashoryu doll that the Japan Sumo Assn. has brought out as part of a line of promotional action figures.

“It looks like me, but the face doesn’t show my seriousness when I’m in the ring,” he complains. “I wish they had made the face look more fierce.”

Other wrestlers say Asashoryu’s “fighting spirit” is what separates him from the pack. It’s evident in the scowl he brings into the ring, the fury in his eyes.

“His personality is not like the Japanese, who are taught to be patient and not misbehave,” says Toshiyuki Hamamura, who recruited and coached Asashoryu at the Meitoku Gijuku High School Sumo Club.

Hamamura says the Mongolians are driven by a hunger to escape the economic underclass.

“Mongolian wrestlers are different from the Japanese,” the coach says. “They have nothing to fall back on.”

Indeed, sumo’s future may lie in its allure to teenagers outside Japan for whom the grind and austere conditions of the sumo lifestyle remain attractive. Why, on the other hand, would Japanese teenagers get up in the predawn cold to endure suffering and pain in the dirt dohyo, they ask, when they could be playing, say, golf instead?

Sumo, unlike hitting five-irons, is a violent mashing of bone and muscle, accompanied by ancient codes of bullying and humiliation.

At a recent practice session, Asashoryu took it upon himself to punish another wrestler whose work ethic was deemed to have faltered. As the wrestler with layers of fat strained against another in the ring, Asashoryu delivered a series of savage two-handed whacks to the back of his thighs, first with a bamboo pole, then with a metal shovel.

The rikishi screamed and collapsed in agony with almost every blow, while the other wrestlers taunted him to get back up and fight. (Who’s going to dare tell the yokozuna to put down the shovel?) When the victim retreated to a corner of the stable, Asashoryu cracked him over the head with the bamboo pole. Six times.

The session ended with the wrestler whimpering and rolling in pain on the dirt floor.

Asashoryu called it a “whipping of love,” arguing that the rikishi would emerge stronger and happier for having “overcome” the pain.

“You have to be strict to make them try harder,” he explained.

And had he ever received such a whipping?

“I always tried hard,” he says firmly.

But there are also signs that Asashoryu is maturing, that he is softening his image to make himself into a yokozuna the Japanese can love.

“He’s still growing up, but he’s trying hard,” says Uragoro Takasago, Asashoryu’s stable master and the target of his ire that summer night. “He has a different background. But without that strong spirit, he wouldn’t be able to accomplish what he has with such a small body.”

Asashoryu doesn’t talk like a rebel crashing the ramparts of sumo’s traditions. He dismisses K-1 as vulgar, burying rumors that he might join his brother on the glitzy circuit.

“What’s interesting about K-1?” Asashoryu asks. “All those guys just like punching people.”

He slips easily into discussions of sumo’s aesthetics, talking about the “beauty of the moment when two wrestlers face each other and crash together.”

Suddenly, Asashoryu is sounding like sumo’s savior, hope from an unlikely source, parachuting in to rescue Japan’s national sport.

“Sumo has preserved its traditions for a long time,” he says. “It is genuine. It’s pure. I don’t want to see it lost.

“I may have been born in Mongolia,” he says, his mouth set defiantly, “but I am a Japanese yokozuna.”

*

Hisako Ueno of The Times’ Tokyo Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.