Using artificial intelligence, researchers are teaching a computer to read the Vatican’s secret archives

- Share via

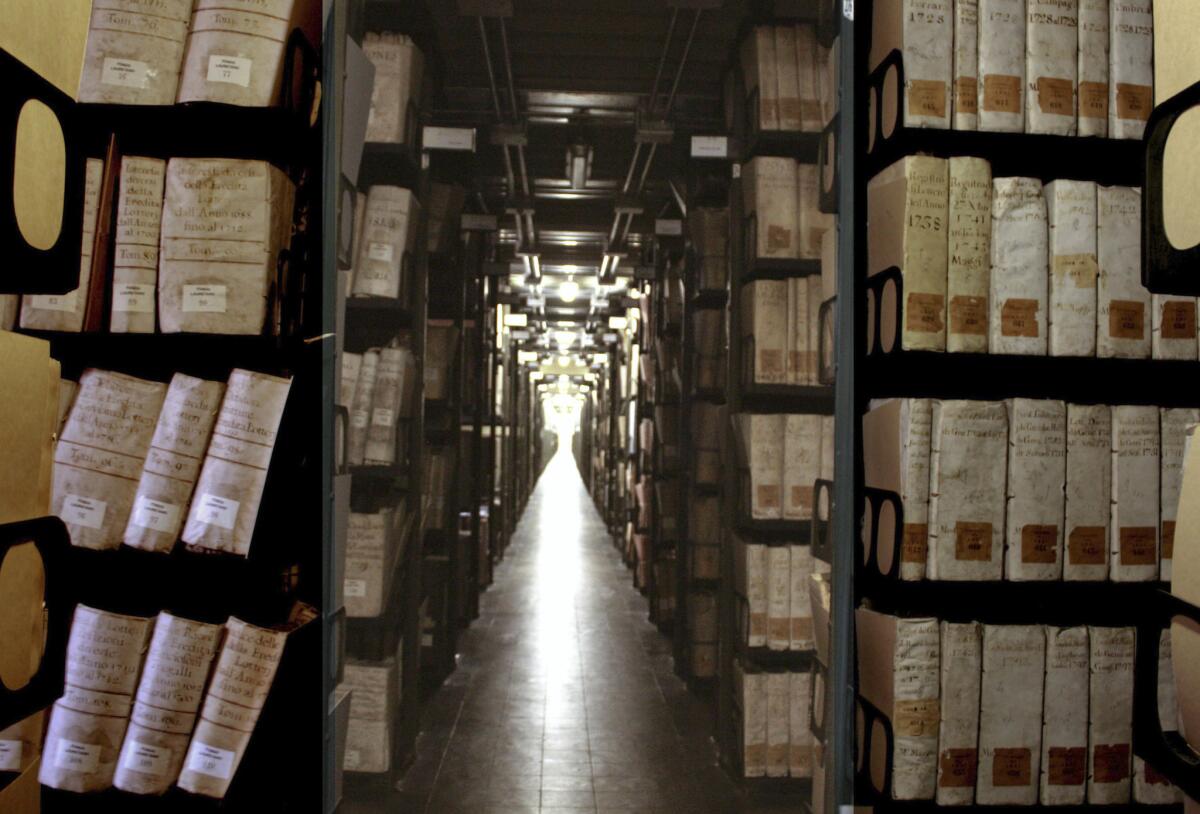

Reporting from ROME — When the custodians at the Vatican’s Secret Archives proudly claim “The history of the whole world is here,” they are not kidding.

The archives’ heavily laden shelves stretch 53 miles down dimly lighted corridors and are packed with papal correspondence dating to the 8th century and penned by the likes of Mary Queen of Scots and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

The only problem: There is so much of it. More than 1,000 scholars are let in annually to scour the shelves, but much has yet to be read, let alone inventoried, digitized or translated.

Which is why one IT professor in Rome decided it was time to let algorithms loose in the hallowed halls of the Vatican, using artificial intelligence software taught to read medieval Latin.

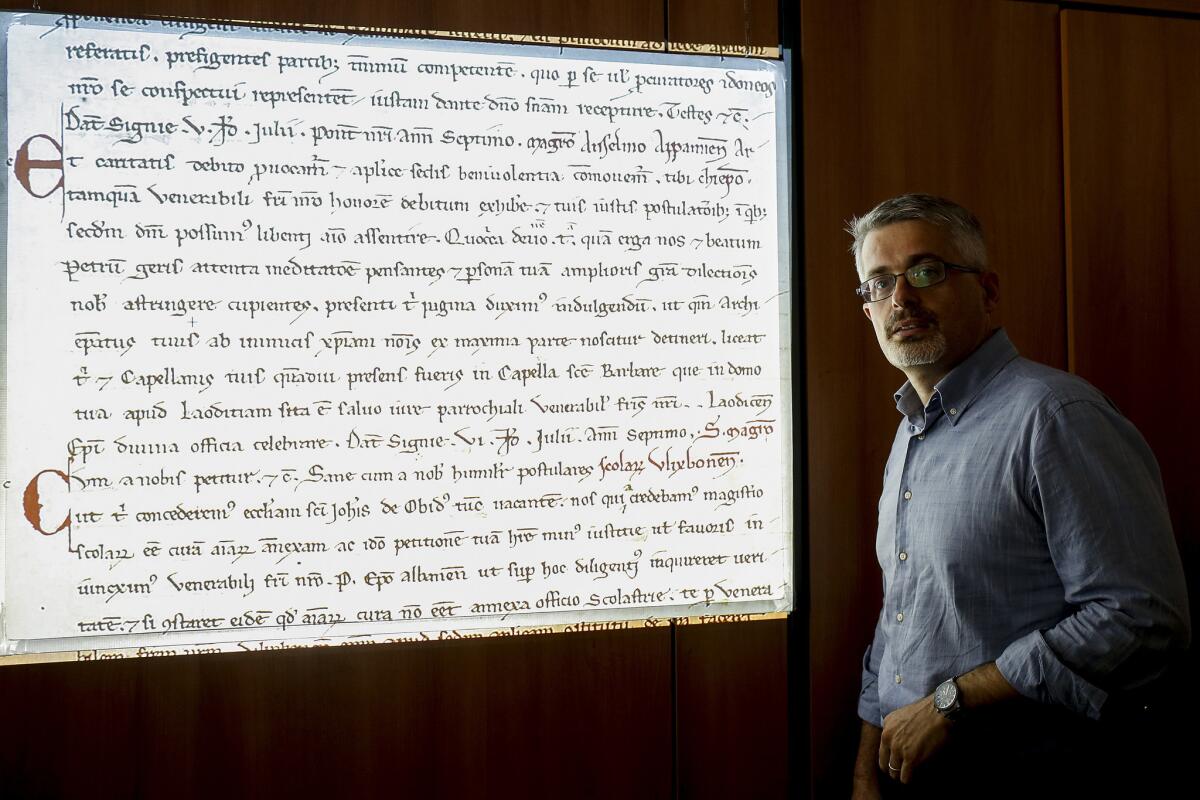

“When I first mentioned my ideas to train a computer to be able to read the 1,000-year-old handwriting of Vatican scribes, I was told it was impossible, but that just spurred me on,” said Paolo Merialdo, a soft-spoken academic at Roma Tre University.

The chance of finding new insights into history was too hard to resist. After all, it was on those shelves in 1920 that archivists stumbled upon a letter, with 81 wax seals attached, sent by British nobles to Pope Clement VII in 1530 demanding permission for Henry VIII to divorce Catherine of Aragon.

Other treasures include a letter from France’s Marie Antoinette just before she went to the guillotine in 1793 and the 1650 note written on silk and folded inside a stick of bamboo in which the Ming Dynasty Empress Wang told the pope that she was converting to Christianity.

From 1887 there’s a letter from a North American Indian chief, written on bark, which addresses the pope as the “Grand Master of Prayers.”

In 1810 Napoleon took the archives back to Paris after occupying Italy. About a quarter of the documents were lost — much of it shredded and sold to a cardboard factory — but the remainder was returned. Some documents recovered still have French reference numbers on them.

Despite the “Da Vinci Code” overtones, the “secret” in Secret Archives simply derives from the Latin for “private” or “personal” because it was the pope’s private collection.

Depicted as a high-tech steel bunker in Dan Brown’s “Angels and Demons,” the archives in real life are a maze of concrete corridors — but as in the bestseller mystery thriller, there are secrets waiting to be found. The 53-year-old Merialdo even has a touch of Tom Hanks about him, showing gritty self-belief as he built an investigative team that now includes Vatican archivist Marco Maiorino.

“I told Merialdo that it would be tough for a computer to read the documents thanks to the joined-up Latin and the abbreviations used by scribes,” said Maiorino. “But I was intrigued because there is much in there which has never been seen.”

“And if a historian has read a page, he or she might miss something an algorithm would catch,” Merialdo added.

The duo were joined by IT academic Donatella Firmani, 34, who explained the team’s challenge by taking a business card and scanning it with her phone, producing an accurate text on the screen.

“That is normal optical-character-recognition software,” she said. “But now watch this.” Scanning a page of medieval Latin, the phone came up with a few lines of gobbledygook and gave up.

To get their software up and running, the team members scanned letters sent by 13th century Pope Honorius III and taught the computer how to read them with the aid of 600 Italian schoolchildren. The students were shown medieval Latin letters, written in the different styles used by Vatican scribes, and asked to identify them on computer screens.

“It’s called ‘pattern matching,’” said Merialdo. “The pupils didn’t need to be able to read Latin, simply find the letters, and by doing it repeatedly, by picking letters written differently, they taught the computer how to do the job.”

The snag was joined-up, or cursive, writing, which confused the computer as it struggled to figure out where letters start and finish — just think of the English word “minimum” written in longhand.

Undeterred, the team fed the computer a Latin vocabulary so it could it get used to common letter combinations — in order to better split them into letters.

“Take the Latin word Huiuscemodi, which means ‘of this kind.’ The handwritten letters uiu might appear as three ‘I’s, but the computer knows that is impossible, or two ‘uu’s, which the computer knows is rare,” Merialdo said. “Another example is how the ‘s’ was often very similar to ‘f,’ but if the computer sees the letter before a ‘c,’ it will know it has to be ‘s.’”

They also programmed the computer to draw vertical lines separating out each individual stroke of the pen.

“The computer looks at all the possible letters that can be built from the strokes and offers solutions using its knowledge of probable letter sequences,” Merialdo said.

A screen flashed the images of Latin words divided into letter combinations by the computer, an elegant, 21st century counterpart to the flowing script of the medieval scribes.

So far, the computer has a reading accuracy rate of 65%. “More like 72% if you allow words with just one wrong letter, and we are still training it to recognize abbreviations,” Merialdo said.

“One example,” Maiorino added, “is the word ‘Epi,’ which was often used to mean “Episcopi,” Latin for “episcopal.”

Next up, the computer will be fed common word combinations and a bit of grammar, boosting its artificial intelligence. The team also found that drawing vertical lines between strokes was tricky when the strokes were diagonal, or when letters overlapped.

“We taught the computer how to paint each stroke with different colors like jigsaw pieces and differentiate them that way,” said Merialdo.

The name of their computer program is In Codice Ratio. “It’s a play on words,” Merialdo explained. Codice is Latin for the documents, but also means computer code in Italian, while ratio means reason in Latin. “It means you will find reason in the documents, and in code.”

By next year, the group hopes to get its program up to 95% accuracy as its members near their ambition of setting it loose on the archives. Although it will not translate the Latin, it will generate digital — and easier to read — versions of documents.

The work is a departure for Merialdo and Firmani, who are more accustomed to developing algorithms used by Siri and Alexa, and building so-called knowledge graphs to help Google answer user questions. “It all started when I realized I was studying the internet, but had the world’s richest archive on my doorstep here in Rome to study,” Merialdo said.

The team’s new passion for untangling medieval Latin is already finding applications in the modern world, far from the hushed reading rooms of the Vatican. “Thanks to this work we have a contract with a company who will use the software for reading scans of crumpled, handwritten receipts, which could be very useful for tax accountants,” Merialdo said.

Maiorino said he was looking forward to the day when Vatican documents transcribed by the software would allow him to do word searches across centuries.

“The Vatican may be the smallest state in the world, but even today it has more ambassadors around the world than any country except the U.S., and we have records of all their correspondence going back 12 centuries,” he said.

Maiorino speaks from experience. In 2012 he was involved in putting together an exhibition of the archives’ greatest treasures, including the 1493 papal bull, or decree, that split the New World between Spain and Portugal after Columbus’ return from the Americas — one of the most important documents in the history of the world.

“We have been joking about how the program will steal my job,” said Maiorino, who is an expert in medieval Latin. “But it will only transcribe texts, while I will continue to translate and interpret them.”

Kington is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.