Pakistan’s Pervez Musharraf flees court after arrest ordered

- Share via

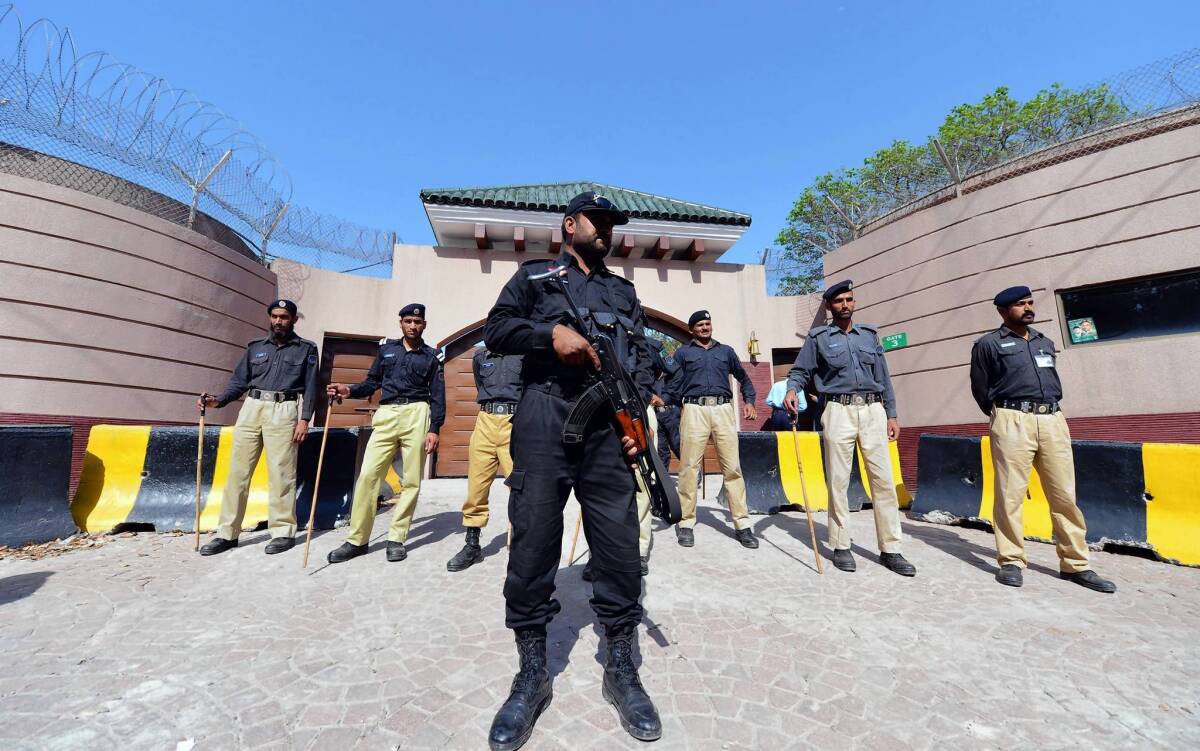

ISLAMABAD, Pakistan — An Islamabad court Thursday ordered the arrest of former military ruler Pervez Musharraf on charges of illegally detaining dozens of judges while in power, but he slipped away when commandos assigned to protect the ex-leader shielded him from police outside the courthouse and whisked him away to his heavily guarded residence.

The ruling by Islamabad High Court Judge Shaukat Aziz Siddiqui provided further evidence that the onetime autocrat miscalculated the extent of his public support when he returned to Pakistan last month after four years of self-imposed exile. This week, a judge in Peshawar barred him from running in parliamentary elections May 11, in effect ending his hope of resurfacing as a major player in Pakistani politics.

Now the 69-year-old former general faces a different challenge: staying out of jail. Lawyers outside the courthouse said the rangers deployed to provide Musharraf security had violated a court order by shielding him from arrest. The commandos would continue to be in violation of the law if they persist in preventing Islamabad police from taking him into custody, they said.

“The security he has been given is only meant to safeguard his life, not to allow him to avoid the law,” said lawyer Chaudhry Muhammad Aslam Ghumman, the chief complainant in the detention case against Musharraf. “They are flouting the law. The people responsible for implementing the order of the court are facilitating the culprit.”

Musharraf’s aides say he will appeal Siddiqui’s ruling to the Supreme Court. Pakistani news reports said that federal authorities might designate as a “sub-jail” the former leader’s compound on the outskirts of Islamabad, in effect putting him under house arrest.

“Pervez Musharraf is not an ordinary man,” said Muhammad Amjad, a spokesman for Musharraf’s new party, the All Pakistan Muslim League. “He is a former president and a former army chief. It would not be appropriate to put him in prison.”

Another spokesman, Raza Bokhari, said in a statement that a Supreme Court rejection of the former general’s appeal could “result in unnecessary tension amongst the various pillars of [the state] and possibly destabilize the country.”

Musharraf’s lawyer, Ahmad Raza Kasuri, called Siddiqui’s ruling biased.

The former general “has been called a dictator, and yet he acted like a democrat and submitted himself before the court. But the judiciary has shown its bias and vindictiveness,” Kasuri said. “This was a wrong decision. The [Islamabad] High Court is not such a sacred cow that its every decision can be deemed legal.”

Musharraf’s return appeared doomed from the start. The tepid welcome he received — only about 2,000 supporters appeared at a Karachi airport March 24 when his flight arrived from Dubai, United Arab Emirates — affirmed the widespread belief that the former general had overestimated his popularity in a country unwilling to forgive him for eight years of corruption and autocratic rule.

He tried to mount a campaign for election, but courts disqualified him on the grounds that he had suspended the constitution while in power.

Meanwhile, Musharraf has been forced to appear in court in three criminal cases pending against him: charges that he did not provide enough security to prevent the 2007 assassination of former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, allegations that he ordered the killing of a Baluch nationalist leader in 2006, and the judges’ detention case. The latter charges stem from Musharraf’s decision in 2007 to purge 60 judges, including Supreme Court Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammed Chaudhry.

Musharraf was army chief of staff in 1999 when he seized power in a bloodless coup. Two years later, he appointed himself president, keeping his role as army chief. He stepped down from office in 2008 to avoid impeachment proceedings.

Lawyers in the courtroom say Musharraf appeared stunned by Siddiqui’s ruling to order his arrest and not extend his bail, which expired Thursday. “He was visibly shaken,” said Saliheen Mughal, a lawyer assisting Ghumman, the complainant. “He was sweating, and obviously he was clearly upset.”

Dozens of commandos escorted Musharraf out of the courthouse, at which point an Islamabad police officer grabbed Musharraf’s arm and tried to arrest him, witnesses said.

At a news conference Thursday evening, Amjad, the party spokesman, denied that an officer tried to arrest Musharraf and said that the former leader would have surrendered had an officer approached to take him into custody.

The personnel guarding Musharraf are members of a paramilitary force that is supervised by army-appointed commanders but ultimately falls under the authority of the Interior Ministry. His return has put the military in the difficult position of deciding to what extent they will protect a former army chief.

“It is essential that Pakistan’s military authorities, which are protecting the former dictator, comply with the Islamabad High Court’s orders and ensure that he presents himself for arrest,” said Ali Dayan Hasan, Pakistan director for Human Rights Watch. “Continued military protection for Gen. Musharraf will make a mockery of claims that Pakistan’s armed forces support the rule of law and bring the military further disrepute that it can ill afford.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.