In Afghanistan, businesswomen must seek a delicate balance

- Share via

KABUL, Afghanistan — Roya Mahboob navigates the potholes of doing business in Afghanistan like any other entrepreneur. Corruption is rife. Kidnappings are common. Bomb blasts remain an overarching reality.

But as the female chief executive of a thriving software firm in Afghanistan’s male-dominated society, Mahboob finds that her potholes sometimes feel like sinkholes.

Banks have balked at lending her money simply because she is a woman. Anonymous emails and text messages have warned her to abandon her work. One ominous missive came on crumpled paper wrapped around a rock and thrown into her front yard. It said: “You’re a bad girl. When you head outside, you’d better be careful.”

“It’s been very difficult for us,” says Mahboob, a diminutive 25-year-old with a soft voice that nonetheless comes across as firm and unhesitant. “When we first went to talk to businessmen, they treated us very badly. They couldn’t believe that women could be technical-minded. They’d make jokes about us. When they smiled, their smile told us that they didn’t think we could do the job.”

Afghanistan has made meaningful strides in women’s rights since the Taliban’s rule ended more than a decade ago. Back then, women were barred from going to school and could not leave home without being escorted by a male relative.

Now, nearly 3 million girls go to school. Women are forging careers in medicine, law and business. In the parliament’s lower chamber, 69 of 249 members are women.

But mistreatment is still prevalent, particularly in villages and rural areas, where some girls are sold to settle disputes and child marriages remain common.

In Afghanistan’s business world, chauvinism takes a different shape. Male colleagues bristle at the thought of a woman competing alongside them or winning a contract they sought.

Afghan businesswomen have to strike a delicate balance: They must be visible enough to nurture new connections and customers but not to the extent that they land on the Taliban’s hit list.

“Most successful businesswomen here, they prefer to be in the background,” Mahboob says. “We still have Taliban here, and we’re afraid of them. If we’re too visible and too many people are talking about you, maybe you will be more successful — but maybe you’ll have more trouble.”

So Mahboob takes measured steps through Afghanistan’s male-dominated business world. She rarely grants interviews to Afghan television, radio or newspapers. She maintains three offices: one in her home city of Herat in western Afghanistan, another in New York City and a third in a small, two-story building in Kabul tucked away in a maze of rutted dirt lanes far from the Afghan capital’s main thoroughfares.

She used to change her cellphone number each month as a precaution but has abandoned the tactic because she lost customers.

Despite the hurdles, Mahboob has, in less than three years, turned her software start-up — launched with four workers and $10,000 borrowed from relatives — into a multimedia moneymaker with pending projects valued at more than $1 million.

Her company, Afghan Citadel Services, operates information technology centers in schools in western Afghanistan, runs an online documentary channel that attracts as many as 3 million viewers a month, sells casual wear online and even owns 10% of a local professional soccer team.

At the moment, she’s seeking investors for her next project: an Afghan television channel devoted to women’s issues.

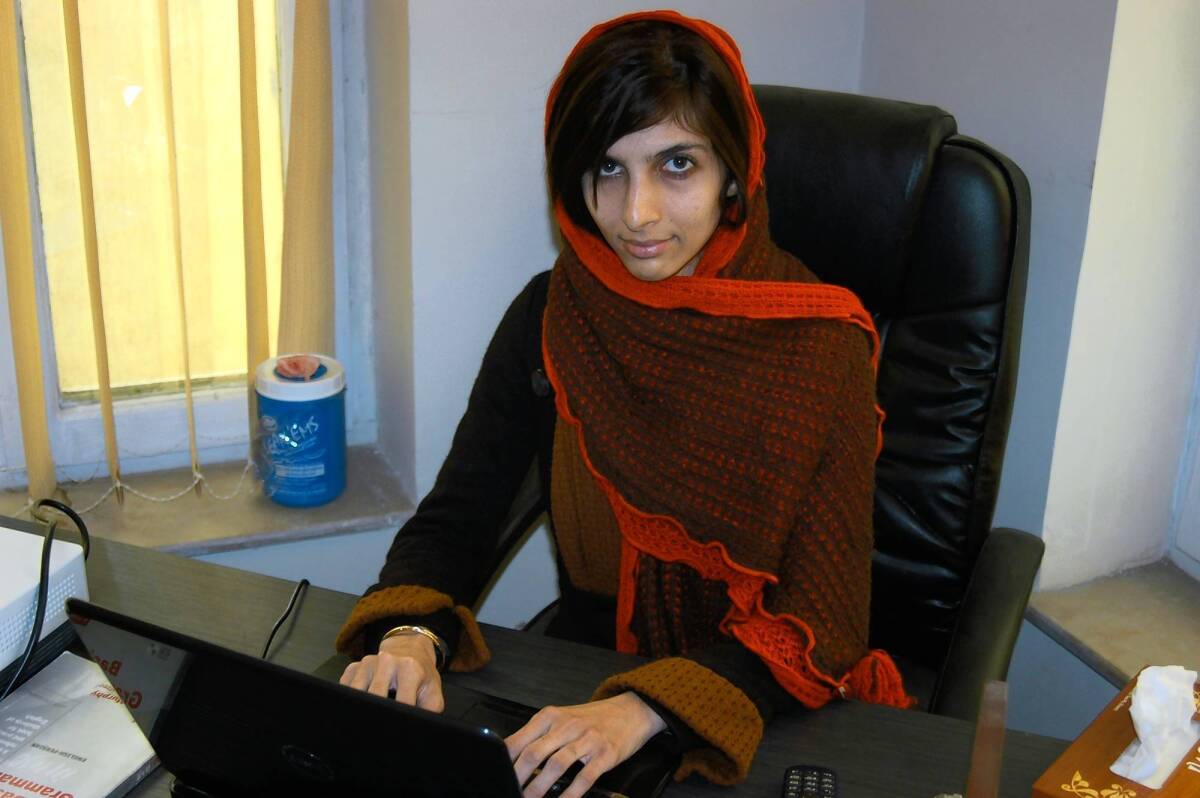

“Media can be a powerful way to tell the government what we want — what Afghan women want,” Mahboob says, seated in front of her laptop, a red scarf wrapped over her jet-black hair. “Using $100,000 to teach 20 women is one thing, but by putting $100,000 into a women’s channel, you can teach millions of women. Television can go to the villages, where it can teach women and empower them.”

Mahboob started her business while working at Herat University as an information technology coordinator. Lacking the money to rent an office, she and her four employees, all university students, worked on their laptops from a cafe. They began winning contracts, but they also ruffled feathers in Herat, a city of 397,000.

Prospective clients liked Afghan Citadel’s work, but they wanted steep discounts because the company was run by a woman and had mostly female employees.

“One of our systems, a Web-based accounting system, cost $2,500, but they were only willing to give us $800 to $1,000,” Mahboob says. “The same system sold by companies run by men cost $4,000.”

Eventually, Afghan Citadel began outpacing the competition and moved into an office building with additional workers. But male competitors seethed with anger.

Three of her female workers quit after receiving a stream of anonymous threats and the company’s website was hacked several times. Mahboob had to fire a male worker who had been sabotaging one of Afghan Citadel’s projects. “He turned out to be a spy, working for a competitor,” she says.

One of Mahboob’s workers, the Herat branch manager, fell prey to fake Facebook profiles that portrayed her as having a slew of boys as friends. “In Herat, if a girl adds boys to her Facebook page, people think she’s not a good girl,” the manager says.

By the summer of 2011, the threats and warnings began to wear on Roya Mahboob. Her parents supported her, but family friends and relatives weren’t as open-minded.

“My father’s friends would say, ‘Why is she working? She doesn’t need the money.’ But I can’t live my life based on what other people are saying. I have to live for myself.”

That summer, she moved to Kabul while maintaining a branch in Herat.

“There’s more freedom here — nobody knows me here,” Mahboob says. “No one cares what you wear, what you do.

“There are other businesswomen here, and when I talked to them, they said they encountered the same problems. But they didn’t stop, and now they have big businesses. That encouraged me.”

She now has 18 employees, almost all of them women. Last fall, Mahboob partnered with an online Italian film distribution platform on a Web channel that broadcasts videos and documentaries about Afghan society. Profits have been used to create information technology training centers at 40 girls’ schools in Herat, she says.

There are no statistics on the number of businesswomen in Afghanistan, but Mojgan Mostafavi, the country’s deputy women’s affairs minister, says the number of female business owners is on the rise.

Mostafavi says the trend should continue after 2014, when most American troops leave the country. But many Afghan women disagree, worrying that the advances made in women’s rights over the last decade could be jeopardized by the U.S. withdrawal and the prospect of Islamist fundamentalists taking on a major role in governance.

“It’s a concern for all women in Afghanistan,” Mahboob says. “If the Taliban comes into government and women’s freedoms diminish, what will women be able to do? Even now, we are still treated badly.

“If the Taliban comes after 2014, we’ll have even bigger problems.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.