In Havana, Fidel Castro’s passing marks the end of an era

- Share via

Reporting from havana — The death of Fidel Castro at age 90 prompted an outpouring of grief in his Cuban homeland on Saturday while touching off joyful celebrations among exiled Cubans in Florida, dramatizing the polarizing legacy of the late revolutionary icon and political strongman.

In Havana, the Cuban capital, the announcement of his death was far from unexpected — Castro had been ailing for years and appeared thin and frail in rare recent public appearances — but a profound sense of loss was evident among many Cubans about the passing of “El Comandante.”

A ubiquitous presence for generations of Cubans since his revolutionary movement improbably stormed into power in 1959, ousting U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista, Castro finally ceded rule in 2008 to his younger brother Raul, who has embraced economic reform at the expense of communist orthodoxy and backed normalizing relations with the United States.

“His death pains me so much. All Cubans are extremely sad,” said Yosnabo Baez, 54, a worker at Havana’s Jose Marti International Airport. “We all knew El Comandante was old and that that this was going to happen, but, still, his passing causes us a profound grief.”

Another Cuban at the airport, Jose Yoel, said simply: “Cuba is in mourning.”

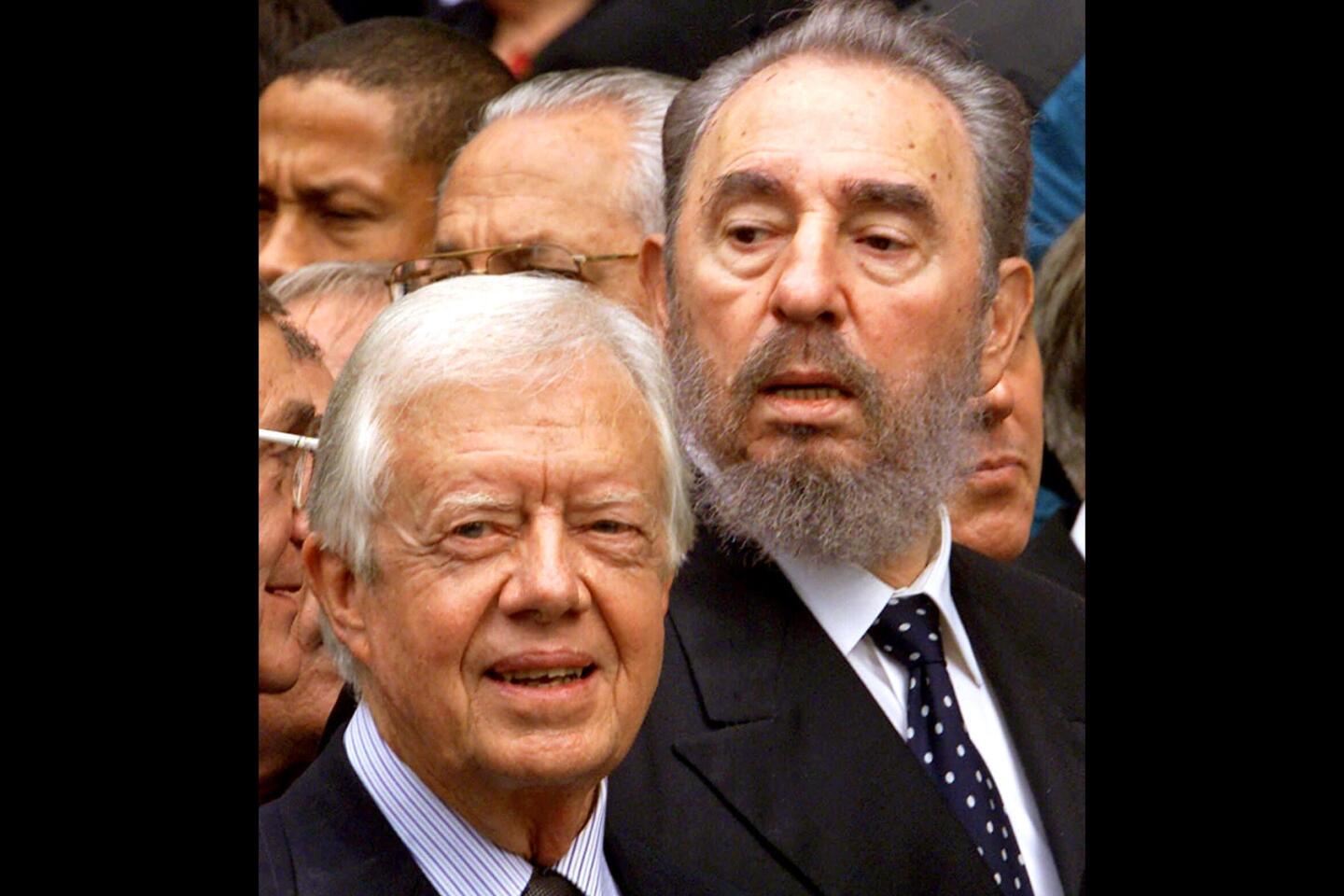

Castro inspired revolutionary movements across Latin America and elsewhere and defiantly confronted what he denounced as U.S. “imperialism,” outlasting numerous White House occupants, while surviving various assassination attempts. He became a signature figure of the Cold War era, the ultimate villain to some, a champion of the underdog to others. To many he was, and always will be, a brutal dictator.

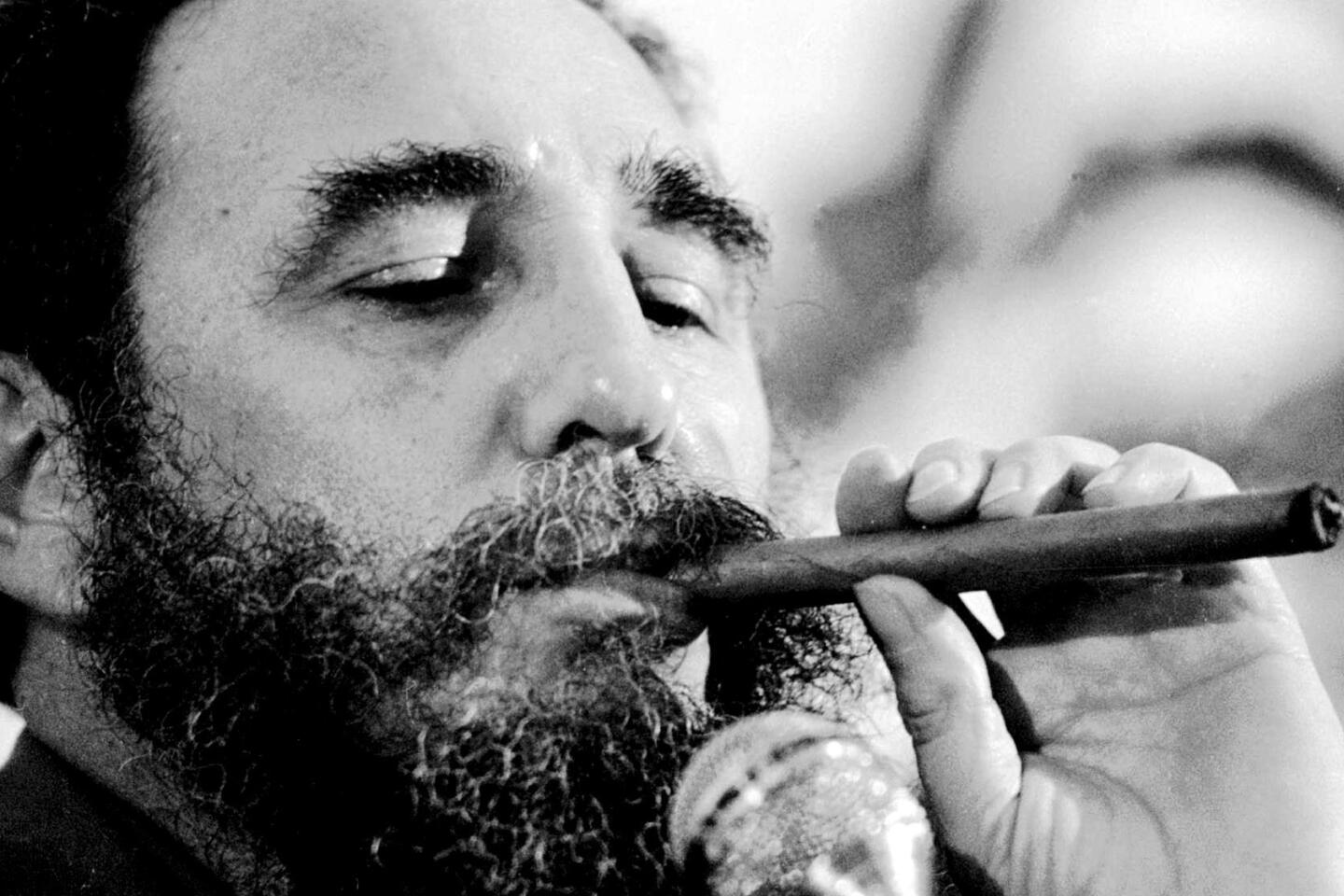

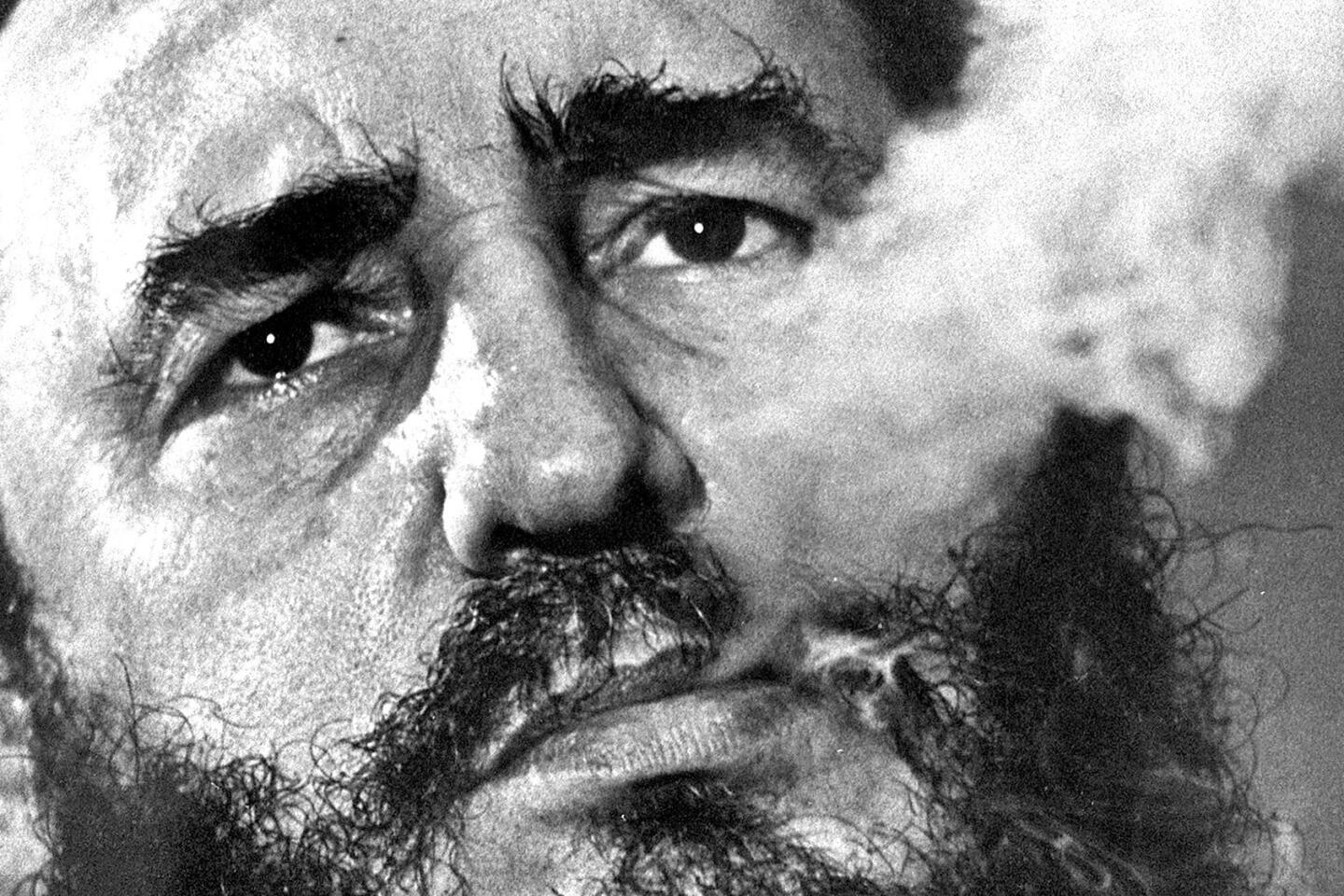

Castro’s rousing slogans, his bearded visage and his often protracted political pronouncements — usually targeting Washington, his eternal adversary — helped shape the island’s collective psyche for more than half a century.

Despite his infirm and retired state, the elder Castro did not hesitate to speak out in recent years, even taking issue with President Obama’s historic visit to the island in March.

On Saturday, the Cuban government declared nine days of mourning. Posthumous tributes dominated local media, as photos of the late “Historic Leader” flashed on television screens and Cubans of all backgrounds spoke warmly, at least in public, of Cuba’s signature personality.

There was no official acknowledgement that, for many Cubans, Castro’s time had long passed.

While appreciating his accomplishments in advancing literacy, education, healthcare and social justice — and in throwing off U.S. domination of the island — many Cubans were fed up with what they viewed as outdated economic policies that thwarted advancement and forced multitudes to flee the country.

Critics also deplored a one-party autocratic rule that throttled free speech in the name of revolutionary solidarity and confronting Washington. To others he was a hero.

“Wherever Castro went in Latin America he received a raving ovation. Why? Because he stood up to the United States, told us where to go, and got away with it,” said Wayne Smith, a veteran U.S. diplomat who served in Havana.

Castro’s ashes are to be taken across the island in a route that mirrors the storied advance of his bearded rebel columns from the Sierra Maestra mountains to Havana.

“There is a great sadness in all of Cuba,” said Zoraida Cruz, another Cuban at the international airport here. “We will always remember how he fought for the Cuban people.”

In the town of Santa Clara, Rodolfo Hernandez, a 26-year-old tour guide, reflected on how the longtime leader would be remembered — and how the nation would move on after his death.

“My first reaction was to think about the ceremony — what are they going to do about Fidel, because he is an important person in our history,” Hernandez said. “I’m pretty sure the whole country will be stuck for a while because he was the main leader” for so many years.

Hernandez also expressed interest in the reaction from Cuban Americans in South Florida, where many “blame Fidel for all their mistakes,” he said, invoking the official disdain toward the exile community.

That reaction manifested itself quickly and exuberantly in Miami’s Little Havana district, long a center of the Cuban American exile community, where people took to the streets, honking horns, banging on pots and pans and shouting, “Cuba libre!”

Some biographers say Castro was haunted by the circumstances of his birth; never christened, he was teased by neighborhood children as “the Jew” and was barred from a Roman Catholic elementary school near home, forcing his exile to a boarding school.

Castro attended a Jesuit academy before studying law at the University of Havana, where he delved into both sports and politics. Tall and powerful, he was a champion basketball player and equally able in baseball, and he was also said to possess prodigious powers of intellect and memory.

Resentful of U.S. backing of corrupt leaders and ownership of exploitative factories and plantations in Cuba, Castro began plotting revolution while still a student, and he found solidarity with leftist student activists throughout the region.

In 1948, Castro married philosophy student Mirta Diaz-Balart; on Sept. 1, 1949, she gave birth to a son named for his father but known throughout his life as Fidelito — little Fidel. Castro’s wife divorced him a few years later while he was in prison, and he acknowledged in interviews having fathered as many as 15 children.

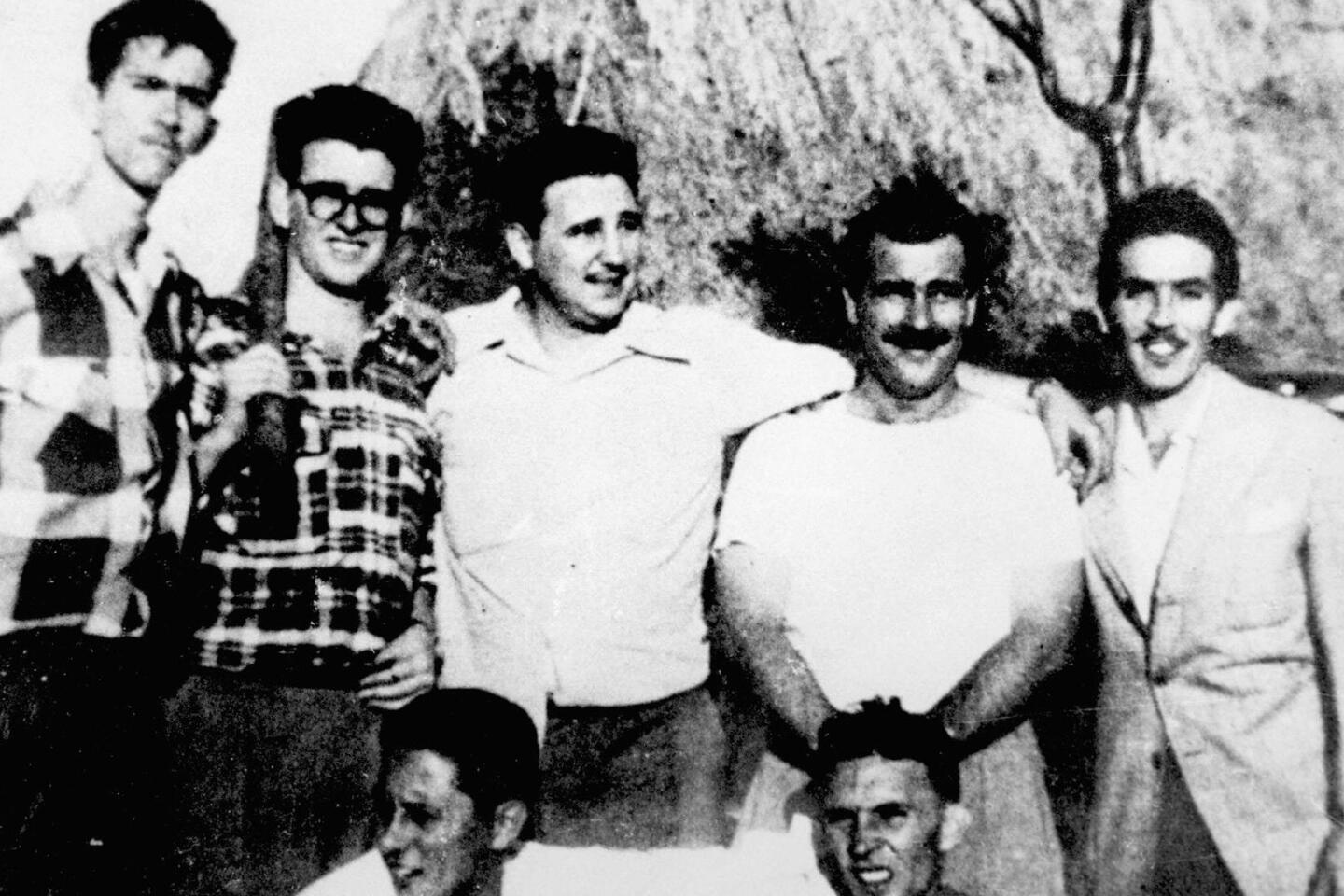

Capitalizing on the Batista government’s unpopularity, Castro organized a revolutionary movement. He had drawn scarcely more than 100 followers to the cause when he led them in an attack on the Moncada military barracks in Santiago de Cuba on July 26, 1953. The assault failed miserably, leaving several dozen of the early revolutionaries dead and scattering the survivors to the mountains of the Sierra Maestra, where they were tracked down and arrested.

Castro drew a 15-year sentence, but was released after two years in a general amnesty and went to Mexico. There, he met an enigmatic, newly graduated Argentine physician with a utopian vision of liberation through armed struggle, Ernesto “Che” Guevara.

Jorge Castañeda, former Mexican foreign minister, chronicled the relationship in his 1997 book, “Compañero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara.”

“Fidel’s passion for Cuba and Guevara’s revolutionary ideas ignited each other like wildfire, in an intense flare of light. One was impulsive, the other thoughtful; one emotional and optimistic, the other cold and skeptical. Without Ernesto Guevara, Fidel Castro might never have become a communist. Without Fidel Castro, Ernesto Guevara might never have been more than a Marxist theoretician, an idealistic intellectual,” Castañeda wrote.

In his biography of Guevara, also published in 1997, Jon Lee Anderson wrote that Castro and Guevara were both spoiled favored sons “imbued with Latin machismo: believers in the innate weakness of women, contemptuous of homosexuals, and admirers of brave men of action. Both were possessed of an iron will and imbued with a larger-than-life sense of purpose.”

Castro, Che and 80 followers left for Cuba on Nov. 25, 1956, aboard the yacht Granma.

When they arrived, the guerrillas took to the mountains, where they organized, trained, recruited and waged a propaganda campaign aimed at intimidating by vastly overstating their numbers and clout.

Frequently short on food and water, the rebels gave up the nuisance of shaving. They became known as los barbudos — the bearded ones — and Castro retained his most distinctive feature throughout his lifetime. The revolutionaries waged a two-year campaign of harassment against the government, culminating in Batista’s decision to flee the country at the start of 1959, effectively giving Cuba to Castro and his forces.

Castro was masterful amid the people, glad-handing flocks of supporters and pumping up nationalist energies. In his signature practice of “direct democracy,” he would rile up a crowd, getting them to chant for an action he had in mind all along, but presenting it as his bowing before the will of the people.

Initially, Castro also found acclaim on the international stage. He charmed journalists and socialites during his visit to New York and Washington in April 1959, though President Eisenhower declined to receive him.

In September 1960, he addressed the United Nations as the recognized leader of his country, upstaging the more dour heads of state with his witty media banter. He emerged as the star attraction, despite a speech that ran more than four hours and U.S. officials’ efforts to isolate him.

Eisenhower slapped a trade embargo on Cuba in October 1960 and severed relations with Havana three months later.

Countless biographers, interviewers and political scientists contend that Washington’s rejection of Castro, encouraged by Batista supporters who had fled to the United States and whose homes and businesses in Cuba had been seized, pushed him toward authoritarianism and into the arms of the Soviet Union.

“The Americans made it impossible for reformers to get any traction, which enforced the role of Che and the radicals,” said Julia E. Sweig, director of Latin American studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. “The Soviet Union became a lifeline because we cut them off economically. It didn’t have to go that way.”

It wasn’t until the eve of the Bay of Pigs invasion, more than two years after he took power, that Castro proclaimed himself a Marxist-Leninist and began steering his country in Moscow’s wake.

The April 1961 invasion was Castro’s legend-making defeat of the U.S. Goliath, after 1,400 invading exiles deposited on Cuban shores by the U.S. Navy were quickly overwhelmed by his determined fighters. The attack served to convince Cubans that the United States bore them ill will, allowing Castro to consolidate power and cast himself as defender of an endangered nation.

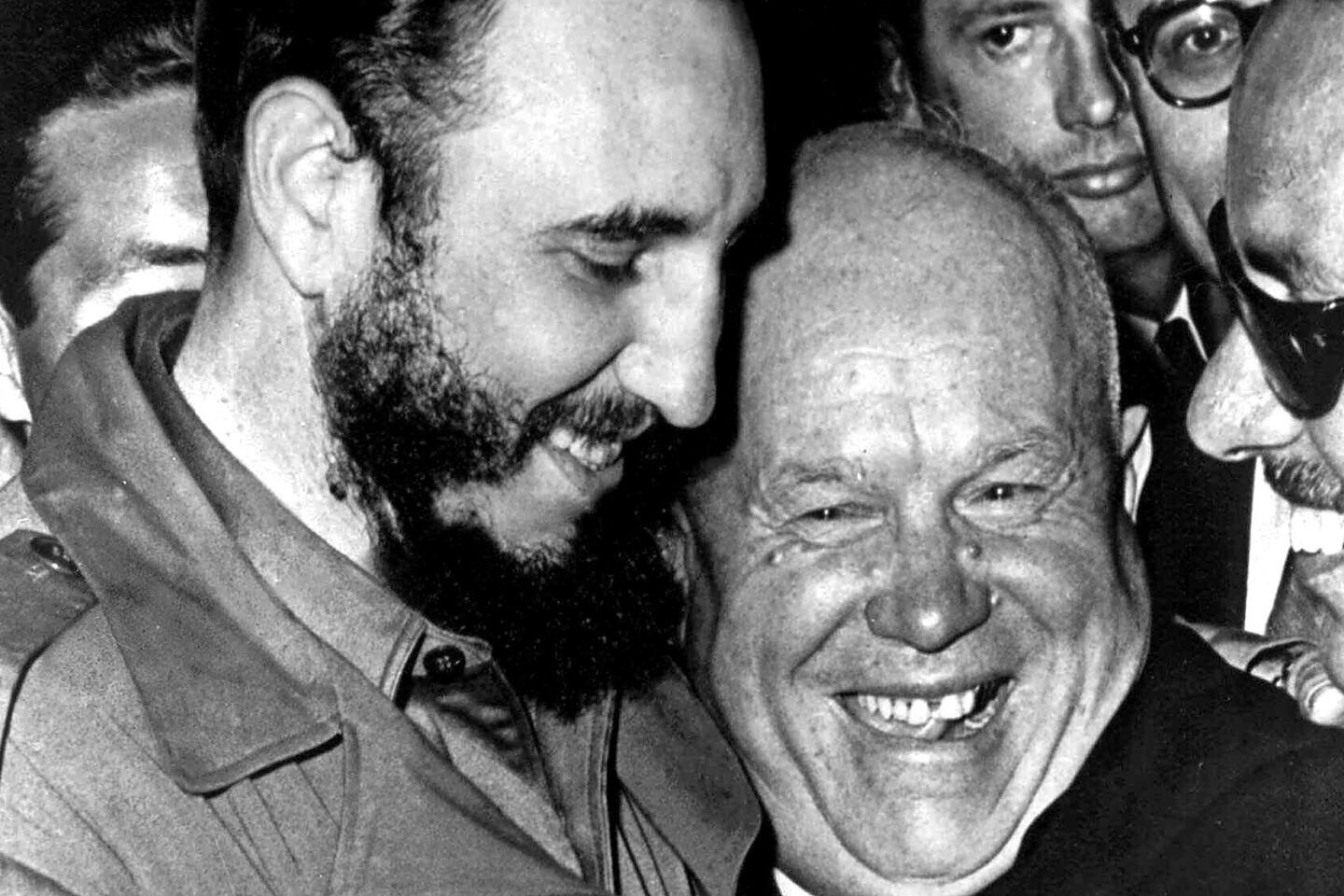

Beholden to Moscow for aid and fearful of another U.S. attack, Castro allowed the Soviet military to install medium-range missiles on Cuban territory in 1962, instigating a high-stakes showdown between the Cold War superpowers that brought the world to the brink of a nuclear war.

During the Cuban missile crisis that October, probably his country’s most stunning moment in the international spotlight, Castro was said to have become enraged when Soviet and U.S. officials negotiated an end to the standoff without his participation.

::

In the name of the Cuban people, Castro nationalized industrial assets across the country, infuriating sugar, rum and cigar czars and laying the foundation for decades of economic conflict with the United States and the dispossessed exiles who fled there.

Cuban exiles in Florida and New Jersey were largely responsible for keeping the sanctions on Cuba. Some also were tied to acts of terrorism against Cuba, including the 1976 bombing of a Cubana Airlines jet in which all 73 on board were killed.

In April 1980, Castro showed his skill at turning defeat into victory by using a refugee crisis, when 10,000 Cubans seeking to flee the island flooded the Peruvian Embassy in Havana. Castro said the asylum-seekers were free to leave from the port of Mariel, and in the chaotic exodus that ensued, he emptied prisons and mental hospitals and sent the inmates to join the flotilla.

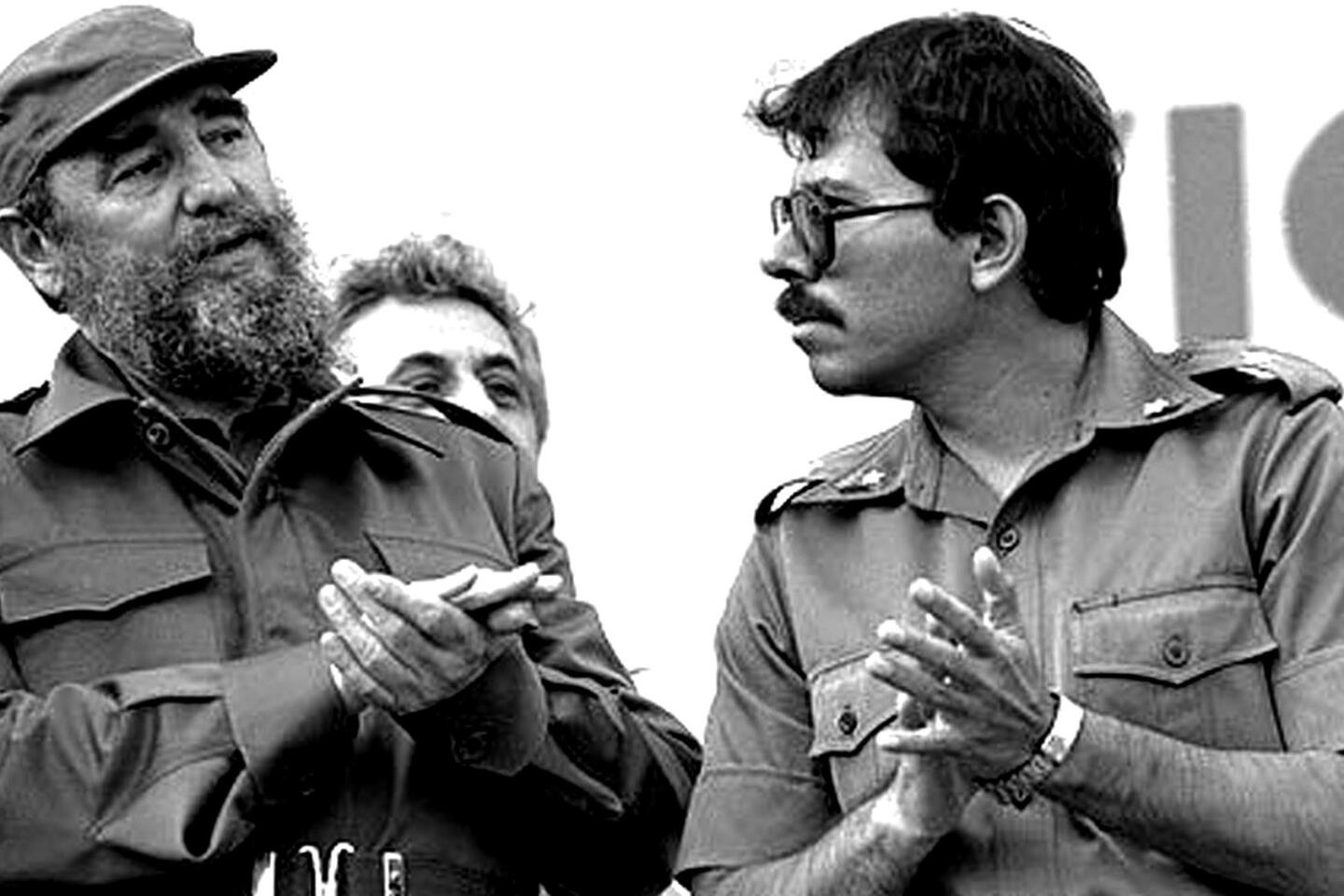

Through his defense minister and brother, Raul, Castro trained and augmented leftist guerrillas around the world starting in the 1970s. At least 2,000 troops died serving their “internationalist” duty, mostly in Angola, and estimates of the true Cuban toll in foreign struggles — a figure never officially disclosed — exceed 10,000.

Although Castro’s forces bested the Bay of Pigs invaders, U.S. troops prevailed in the 1983 clash on the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada, the only time the two armies have fought.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the loss of the $6 billion in annual subsidies Moscow had provided Cuba eventually forced Castro to call home his troops.

Despite economic problems, Cuba made impressive progress in literacy, higher education and healthcare during Castro’s reign.

University enrollment was higher than in many more prosperous countries. Castro’s “literacy brigades” helped lift the quality of life in the countryside. Infant mortality and life expectancy also improved dramatically and are now equal with those of the United States.

Though never clearly embracing the atheism espoused by most communist leaders, Castro banned public celebrations of Christmas until Pope John Paul II made reversal of that order a condition of his historic 1998 visit.

After the Soviet Union’s dissolution and an abrupt end to Moscow’s subsidies to Cuba, Castro agreed to allow some minor economic liberalization to attract foreign investment.

Cuban state companies collaborated with Canadian, Japanese and European counterparts to create a thriving tourism sector on the tropical island, undermining the U.S. embargo. The U.S. government put up barriers to its business community’s investment in Cuba — what increasing numbers of agricultural traders and others lamented as missed opportunity in recent years.

But other parts of the economy felt the effects of the end of the Cold War keenly. Once reliant on plentiful Soviet oil, Cuba turned to Venezuela, which became its key trading partner, providing half of its oil needs on preferential terms. A slump in sugar sales and wildly fluctuating worldwide prices for nickel also hurt.

Hundreds of thousands of Cubans with relatives abroad were able to sustain themselves through the estimated $1 billion in remittances coming to the island each year.

On Thanksgiving Day in 1999, a 5-year-old Cuban boy named Elian Gonzalez was found off the coast of Florida’s shore, one of only three survivors of an ill-fated escape in which his mother and 10 others drowned. The subsequent custody battle between Elian’s anti-Castro relatives in Miami and the Cuban government ultimately gave Castro a platform to bolster his image as protector of Cuban sovereignty and dignity in the face of Yankee aggression.

U.S.-Cuban tensions seemed to be easing when, in 2003, the Cuban government jailed 75 dissidents pushing for democratic reforms. The last of them were finally released in 2011.

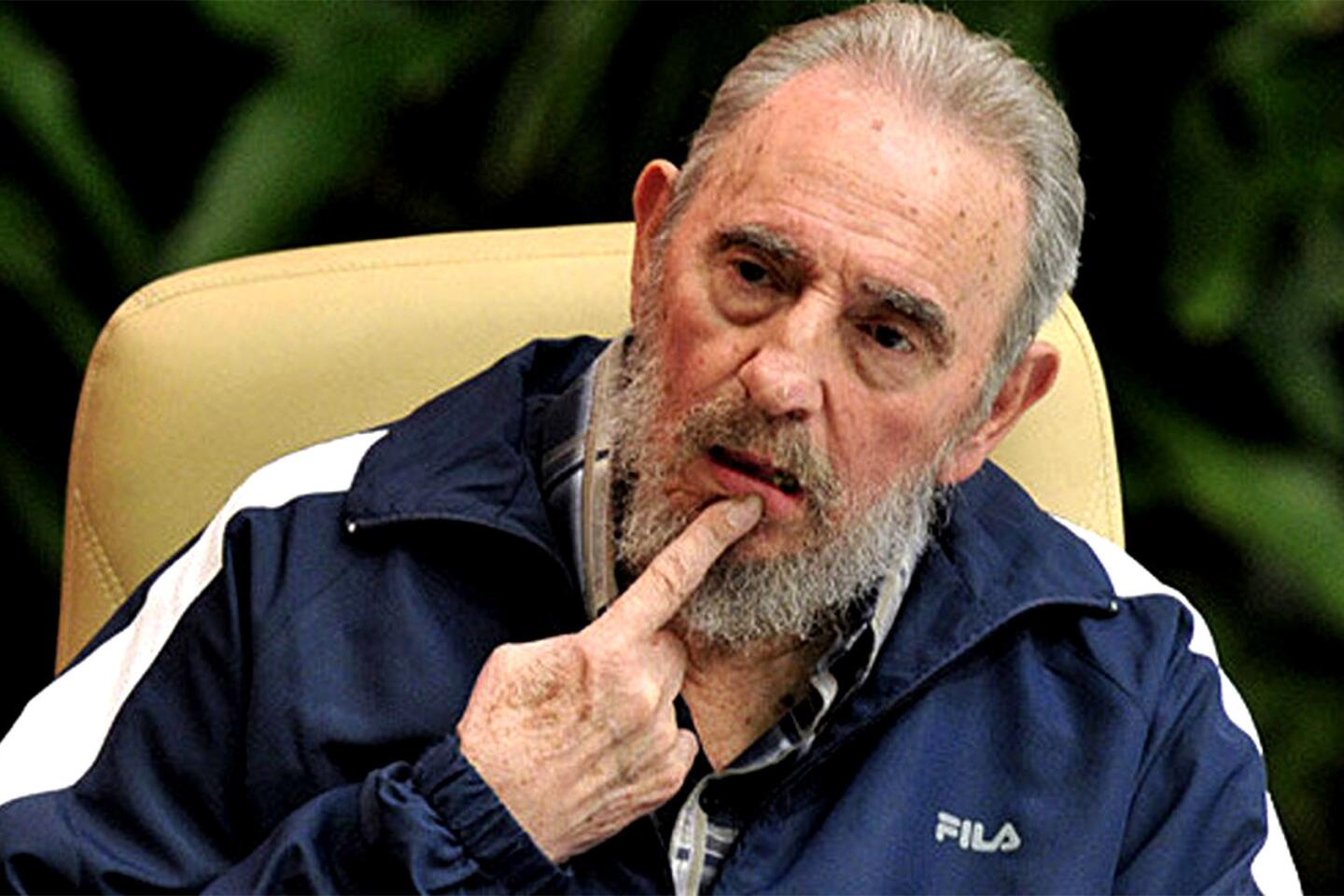

In his later years, Castro appeared increasingly frail. It was his hectic travel schedule in July 2006 that he blamed for the intestinal bleeding that led to surgery and compelled the first transfer of governing authority to his brother.

And it would be years before he reappeared in public, his illness and long convalescence even forcing him to miss the 50th anniversary celebrations of the revolution on New Year’s Day 2009.

Instead, Castro expressed his thoughts in columns he purportedly penned and regularly published in the Cuban press and on the Internet, under the title “Reflections.” He wrote at length on themes including U.S. politics and a looming nuclear holocaust until the last few years of his life.

But in April he rallied enough to surprise the country with a surprise speech at the Communist Party Congress in Havana.

As Fidel Castro’s official role faded (he relinquished his last leadership post, as head of the Communist Party, in April 2011), Raul consolidated his own power and embarked on a reform program that would have been unthinkable under his brother. The changes included allowing Cubans to buy and sell cars and homes, to open small businesses and to leave the country without first applying for government permission.

In March, Obama became the first U.S. leader in nearly 90 years to visit the island nation, and in October he lifted several trade restrictions, a move that included an end to limits on the Cuban cigars Americans can bring home. Administration officials said at the time that the Obama was using the new rules to expand and solidify its opening to Cuba before Obama leaves the White House in January.

Castro did not publicly comment on the warming relations between the U.S. and Cuba, but this year did take swipes at his old rival.

He wasn’t impressed when Obama, in a television address to the Cuban people during his visit, struck a conciliatory tone, saying the two countries “can make this journey as friends, and as neighbors and as a family — together.”

In a long written response, Castro said Cubans could provide for themselves.

“We do not need the empire to give us anything,” he spat.

In another long letter released as Cubans marked his 90th birthday in August, Castro criticized Obama again for a speech the U.S. president had given months earlier during a visit to Japan. Castro’s complaint: Obama failed to apologize for the U.S. bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II.

To the end, Castro clung to his belief that his revolution had succeeded in lifting a nation above self-interest and material obsessions.

His words to the court that tried him for the Moncada attack more than half a century ago echoed throughout his long career and late-night monologues. “Judgment is spoken by the eternal court of history,” Castro said then of his actions. “Condemn me, it does not matter. History will absolve me.”

Besides Raul, his survivors include his longtime partner, Dalia Soto del Valle, son Fidelito, two daughters and six other sons — five born of Soto del Valle.

Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau reported from Havana, Williams from Los Angeles and McDonnell from Boston. Times staff writers Tracy Wilkinson in Washington and Warren Wolfswinkel in Santa Clara, Cuba, contributed to this report.

ALSO

Fidel Castro dead at 90: The revolutionary icon’s influence was felt far beyond Cuba

In Miami, Cubans whoop, dance and celebrate Castro’s death

History will judge Castro’s era, Obama says, as world leaders react to former Cuban leader’s death

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.