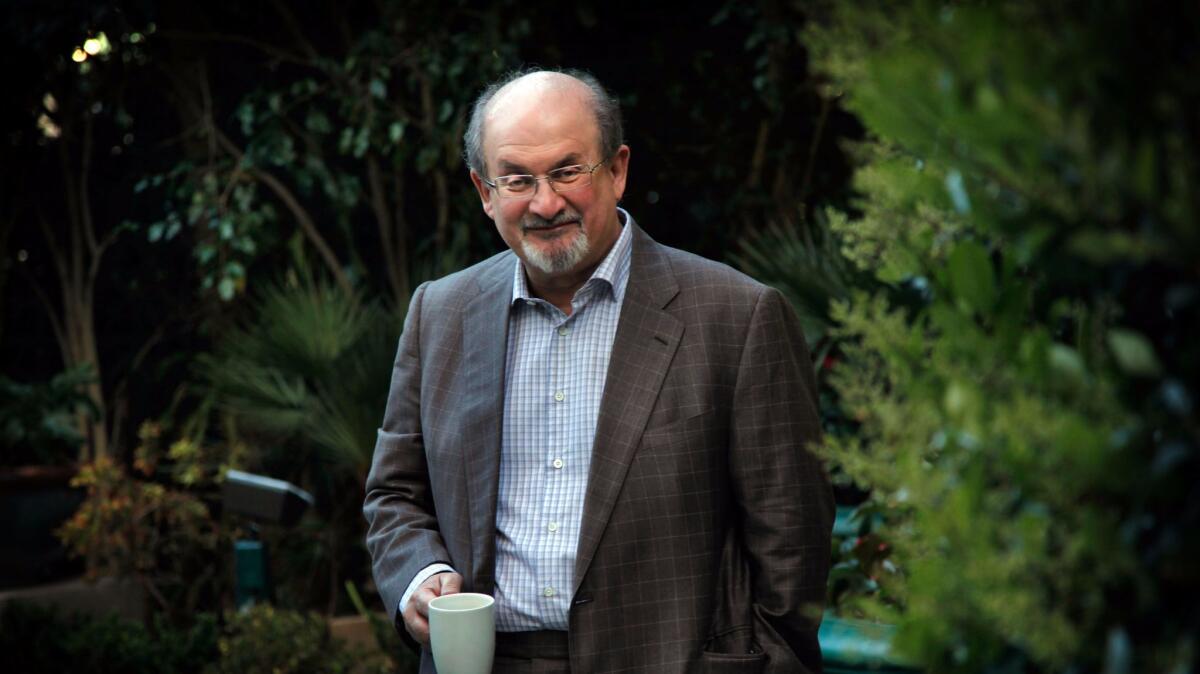

Salman Rushdie on the opulent realism of his new novel, ‘The Golden House’

- Share via

Reporting from New York — “I’m on the Technicolor end,” said Salman Rushdie. He was talking about the kind of realism you’ll find in “The Golden House,” his new novel. “If realism goes from Raymond Carver to James Joyce,” he explained, “It’s realism, but it’s kind of amped up, boosted.”

Interviewed in the Manhattan office of his longtime agent, Andrew Wylie, Rushdie was jovial and charming, a voluble conversationalist not only about the art of fiction but also on topics as diverse as the politics of place names and the different ways to grip the paddle when playing ping-pong. Toward the end of a day of media interviews, the 70-year-old author’s (very nice) suit may have been a bit rumpled, but the man himself seemed in fine form. Some writers don’t much like talking to reporters; Sir Salman Rushdie is not one of them.

For Rushdie, who said he felt “a kind of personal revolt against magic realism,” the idea of writing about today’s political and social landscape sent him back to writers like Stendhal and Balzac, and that greatest chronicler of New York, Edith Wharton.

Set during an era of rapid social change, from the first Obama inauguration to the present day, “The Golden House” (Random House, $28.99) is about a mysterious family that moves to New York with changed names, seemingly endless financial resources and a hidden history of bad, bad things. Patriarch Nero Golden and his three sons (their names, also borrowed from classical mythology, are Petronius, Lucius Apuleius and Dionysus) have fled trauma in their first home, “the city that could not be named” (it’s Rushdie’s birthplace, which he still calls Bombay). They settle in the Gardens, a bucolic block in the bustling West Village, an Eden nestled into the heart of Sodom. But they cannot escape tragedy.

What is it in the age of Trump and Trumpism, to be American?

— Salman Rushdie

The material is rich for a satirist of Rushdie’s wit. The novel includes characters from all spectrums of politics, neurodiversity and gender. Still, he worries that an obsession with identity can fracture coalitions in a politically fraught time. “It ties into a larger subject of American identity: What is it in the age of Trump and Trumpism, to be American?” he asked. “Why are we splitting hairs when there’s a monster coming at us?”

Get tickets to see Salman Rushdie at the Ace Theatre Sunday Sept. 17 at 5 p.m. »

When asked if he’s worried readers will be offended by his treatment of gender or other identity issues, he laughed, a little bitterly. “I’ve offended people before.” Rushdie, famously forced into hiding after a fatwa was placed on him by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, is dead serious about the danger he sees in anti-intellectualism, fascism, religious fundamentalism and sectarianism.

Life in Trump’s America is itself somewhat surreal, he pointed out. “I mean, how did university professors, journalists and writers become the elite? Meanwhile there’s a government which has more billionaires in it than at any point in American history. It’s an amazing reversal of meaning.” Then there’s Trump’s slogan. “When was America great?” Rushdie asked. “Was it before women had the vote? Was it when there were slaves? When was that moment of American greatness to which we aspire? It doesn’t exist.”

The book’s narrator René, a neighbor, watches the Goldens from afar, and then becomes enmeshed in their lives via a film project. “When I was first thinking about it, I didn’t know that René was going to be a filmmaker,” Rushdie said. “I thought in some tedious way that he might be a writer.” Giving René that vocation, he added, “freed up a lot of things about the form of the book, and being able to use movie references as reference points, and I liked all that. And there’s a kind of montage, a cross-cutting between scenes.”

Borrowing a phrase from the character, Rushdie said, “There’s a term that René invents for the movies he wants to make where he calls it operatic realism. And I thought, that’s kind of what I’m trying to do here.”

The whole Brexit thing was a retreat into a fantasy of England, some imagined moment in which everybody wore straw boaters.

— Salman Rushdie

“The Golden House” is of course more than a cinematic page-turner. At its heart it is a paternal tragedy — a father who tries to protect his children from the dangerous, criminal world he’s helped build, only to fail, over and over again. Questions of good and evil abound in the novel, and eventually even René must confront his own moral test.

“Much of the book is tragic,” Rushdie said. “I think some of it is funny-tragic, but I thought of it in a way as a private tragicomedy inset inside a larger public tragicomedy. The reason the Gardens as a setting was so helpful is that it makes that physical: there’s this physically enclosed space, like a little theater, in which the characters can act out their lives. But it’s also a secluded space. And around that secluded space there is the larger tragicomedy of America.”

Rushdie triangulates his understanding of contemporary politics from three nations where he has lived: America, England and his native India. “Independent India as created by Nehru and Gandhi and others was created to be a secular state, in which there is no mention of religion in the constitution,” he said. The present government is both ultra-conservative and Hindu nationalist. “They’re now trying to not just rewrite that to make it a Hindu state in which everyone else is essentially a second-class citizen, but even to rewrite the history books in order to erase the centuries of Islamic rule or to rewrite them as extremely damaging.”

I’m an American. I’m an American novelist.

— Salman Rushdie

“In between is the third country that I spend my life thinking about, which is England,” Rushdie said. “The whole Brexit thing was a retreat into a fantasy of England, some imagined moment in which everybody wore straw boaters. They were glorious and they ruled the world. And the fact that all this was based on the exploitation of an empire, we just agree not to mention that.”

His own identity has long included all three countries, but Rushdie is now a citizen of the place he lives. “I’m an American. I’m an American novelist,” he said. “I became annoyed with myself to not have a vote. I just thought, I live here, I’m not going anywhere, I’ve got roots here.”

The citizenship ceremony itself was powerful, he said. “They are very simple words. They’re not an orator’s words, they’re not poetry. But they’re simple, powerful words — as is the marriage service. You’re saying very plain things, but you’re saying very important, powerful things. It had the same feeling.” Afterward, he said, “I came out transformed. I got into a cab, just an ordinary yellow cab going home. I was looking out at the streets of the city where I’d lived for a decade and a half at that point, and I thought, you know, my relationship with this place just changed completely. The phrase ‘my country’ occurred to me, which it would never have occurred to me before.”

In the end, “The Golden House” moves beyond its social realism to become a sort of love story — both among characters and with their vexed, troubled country. “People always tell me that I’m a hopeless romantic,” Rushdie said. “I think of that kind of as an insult, so I resist it. But apparently I am. Certainly I’ve increasingly found in my writing that love becomes the dominant value, in a way that it wasn’t so much when I was writing ‘Midnight’s Children’ and ‘Shame.’”

“There’s an obvious thing, which is that during those very bad years of my life it was very much the love of friends and family that got me through. So I learned that lesson.”

He still has a souvenir from his citizenship ceremony. “They give you a little flag. They insist on giving you a little flag.” What did he do with it? “I have it. It’s stuck between two books in my library.”

Tuttle is the president of the National Book Critics Circle.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.