‘Working’ on Labor Day with Studs Terkel

- Share via

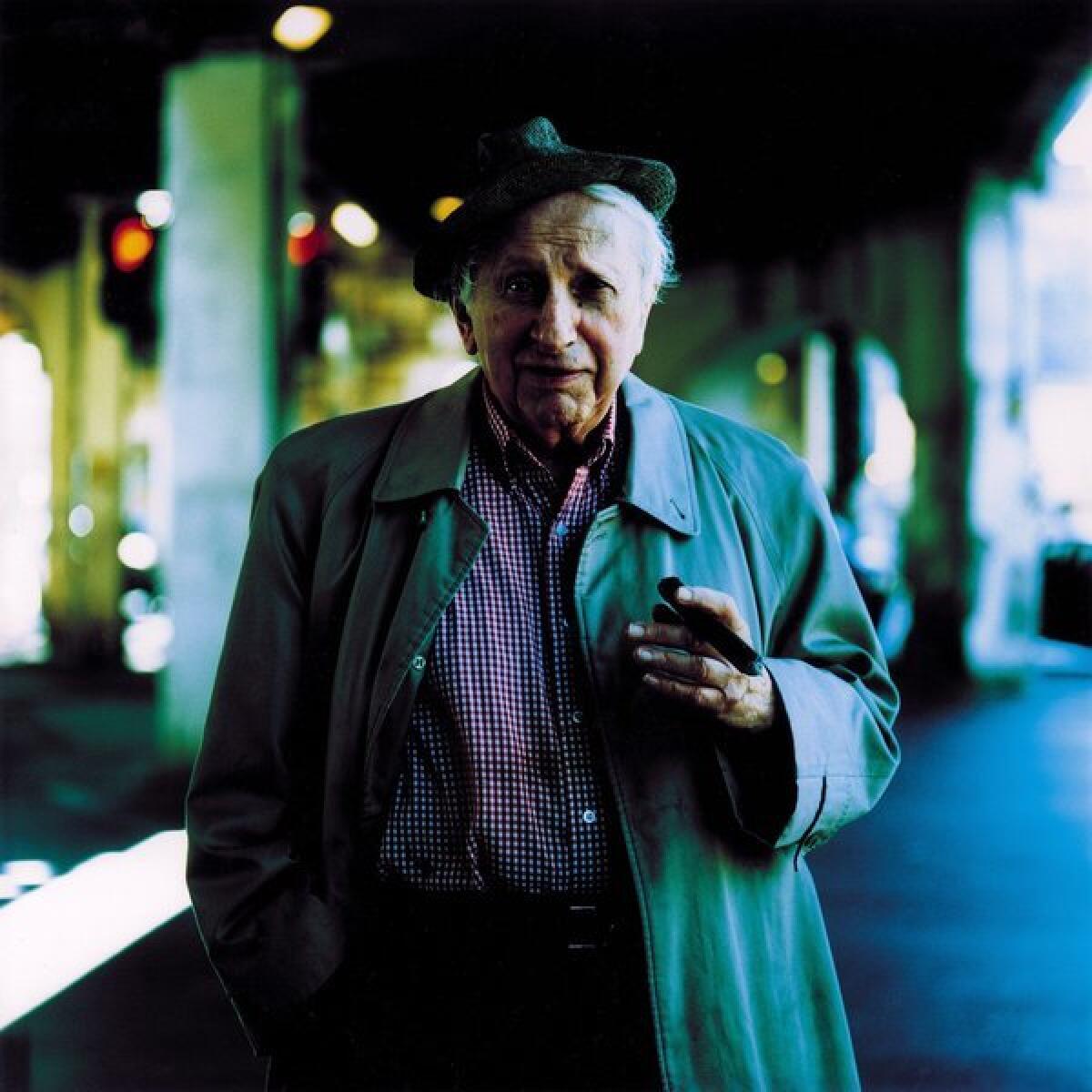

Studs Terkel was a master storyteller, or maybe story-listener. His oral histories showed that with the right ear, he could make an interview something special -- he got to the heart of things, to the hearts of people.

His book “Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do,” published in 1974, became a smash hit -- in Terkel’s hands, the work lives of everyday people became fascinating.

This is our 1974 review of the book by the L.A. Times’ Robert Kirsch. It began with a quote from the Bhagavad Gita, “What is work? and what is not work? are questions that perplex the wisest of men.”

What Studs Terkel uncovers in “Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel about What They Do” is a kind of living theater, captured on a tape recorder, transcribed and then edited down so that the character, tone, introspection and drama are retained. We hear these people and recognize them -- partially -- for the great accomplishment is the depth of the penetrations -- to dream, to fantasy, to illusion.

It seems such a simple idea. Like Terkel’s previous books, “Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression” and “Division Street: America,” the idea came from his editor at Pantheon, Andrew Schiffrin, and Terkel acknowledges his help and the help of others. But in the event, the book which emerges is the product of Terkel’s particular talent, which can be called interviewing, but is really something more than asking questions and listening for answers. The result, as you see, is far from simple.

Work is one of those basic human activities so crucial to life and identity that to pursue the detail of doing and the feelings it compels inevitably leads to something more: the way we feel about ourselves and our experiences, our children and our friends -- and enemies, our country and the way we live, our past, present and future. For the subjects, and for the reader, the book is a deep penetration of American thought and feeling, evokes the lives of more than 130 men and women in their own words, candid, insightful and honest, challenges them and us to the hard question of those homilies, banalities and Fourth of July abstractions which our politicians recite with such smug certainty and more often than not with self-delusion.

It is in its way, a masterpiece of the art of conversation. That said, the question is begged: Can conversation be an art? The way Terkel does it, it is, if art is that kind of activity which draws from ideas, experiences and emotions; matter so shaped that it compels in us expansion and awe, a recognition of the familiar in new ways, a surprise in the ordinary.

A few of the names of those who talked with Terkel you will recognize: the actor Rip Torn, the film critic Pauline Kael, the football coach George Allen. But most of them you won’t -- Hots Michael, a bar pianist; Donna Murray, a bookbinder; Fritz Ritter, a doorman; Tom Patrick, a fireman; Therese Carter, a housewife; Pierce Walker, a farmer. And others: an elevator operator, a spot-welder, a waitress, a stewardess, a teacher, a jockey, a gravedigger, a meter reader, a salesman, a supermarket checker, a copy boy, a president of a corporation.

Crafts and professions, vocations and skills, have, as the medieval apprenticeship indentures tell it, their “mystery.” To tune a piano, or make bed in a hospital, to sell a car or play professional hockey, to pick crops or write a press release, involve doing things in a certain way. But all work in its specific settings in turn shapes those who do it. Real people are not yet robots, automata or units of statistical data, and Terkel is above all interested in seemingly ordinary people.

His art, too, has its mysteries. But no less than the people with whom he spoke in living rooms, on airplanes, he does reveal himself. Interviewing is more than the work of asking questions, or even finding the right people to talk to. It can be an art. We cannot know precisely why one man, past 80, who grew up in Chicago, studied law, but never practiced, became an actor in radio soap operas, a disc jockey, a sports commentator, a television MC, runs a radio program, talks to himself on the elevated, can, in a society filled with interviewers, journalists, talk shows, manage to elicit what most fail to touch, the essential identity of the person which whom he speaks. This has more to do with talent than technique.

But it also has to do with personality. Terkel listens but he is neither transparent (an extension of tape recorder and lens) nor intrusive (no William Buckley). He is thoughtful and perceptive -- most of all open to learning, astonishment and surprise, cognizant of his own illusions and actions, but most of all, and here perhaps we come closest to the possibility of art, ready for risk and serendipity.

He is himself work-oriented, but not so driven that he cannot see the other territories of amenity and grace. “It was the Brooklyn fireman who astonished me into shame,” he tells us. “After what I had felt was an overwhelming experience -- meeting him -- he invited me to stay for supper. ‘We’ll pick up something at the Italian joint on the corner.’ I had already unplugged my tape recorder. (We had had a few beers). I remember the manner in which I mumbled, ‘I’m supposed to see this hotel clerk on the other side of town.’ He said, ‘You runnin’ off like that? Here we been talkin’ all afternoon. It won’t sound nice. This guy, Studs, comes to the house, gets my life on tape, and says, ‘gotta go...’” He asks himself, “... How could I have been so insensitive.”

But that is evidence enough of his own sensitivity. For something emerges in these encounters, made explicit in the introduction, certainly implicit in the interviews. The experiences are revelatory. Not just a matter of record. The conversation can transform. “On one occasion, enduring a playback, my companion murmured in wonder, ‘I never realized I felt that way.’ And I was filled with wonder too.”

Wonder is the precise word for our response as well. Some of patterns and themes have been explained to us buy sociologists and anthropologists. It is not new that assembly-line workers feel robotized, out of touch with what they produce. Not new that in vast conglomerates, people feel like numbers of things. Not new, that people are in despair about meaningless work. But the revelations come in unexpected eloquence, in insights and astonishing rebellion and search.

Terkel would be the last to claim that only this selection of Americans describing themselves and their work could produce a book of this power. Another group, just as diverse and varied, might say things unsaid here, or say the same things in different ways. In this lies the whole point of the book; it is a celebration of individuals, attractive and repulsive, happy and unhappy, relatively free or trapped, holding visions or suffering nightmares. This is another clue to why I call this art, rather than science or ordinary journalism. It is not a cross section, statistically valid, a sociological study, though it informs sociology. It is not pure transcription. It is a rendering, convincing in its own terms. It is rather closer to what Arthur Miller called good journalism, the report of a nation talking to itself.

And we are the witnesses, part of the experience. At every point, we are called upon to ask ourselves the questions these people answer. Don’t expect a celebration of the work ethic, that preachment we hear so much about, usually from those who have come a long way from the kind of work most people have to do. There is a mystique of work which can give savor and purpose and even joy for its own sake. But there are people whose work makes them feel phony and fraudulent, makes them feel like automata, a lot of others who believe their jobs belittle them, or fail to challenge them, or make them feel trapped. And sometimes their jobs can do all of these things at once.

Anthony Ruggiero enjoys his work as an undercover investigator for a private agency specializing in industrial security. (One surprise in the new world of work is how many people are employed watching other people nowadays). His job changes. He feels like an actor. He is not stuck in an office from 9 to 5. But in the conversation his wife, Diane, keeps breaking in, a kind of Greek chorus.

Ruggiero: “I never thought I’d catch the guy. I met my deadline.” The man had been stealing butter from a bakery for which he had worked for 25 years.

Diane: “You want it honestly? I can see sometimes where it really makes him feel bad. Where he really feels like a villain....”

Ruggiero: “They fired him... Sure it bothers me that the guy lost so much. I don’t know if I was mad at the guy for bein’ so stupid to pull something’ like this or what.” Reflectively, “These people are not criminals, they’re just like you and I. They feel they can away with somethin’. Whatever his reason was I don’t know. I don’t think it was money.”

Terkel stands out of the way. The people talk here: it is their time, their work, their lives. Somehow, they manage to reflect a dual angel of vision. The personal experience is not untouched by the times, the culture, history itself. Work changes and the attitudes change. But, this is not just talk. There is another language, several modes of expression. “It is about ulcers as well as fistfights, about nervous breakdowns as well as kicking the dog around.”

Most of all, it is not material to program for computers. Within most of the people there are ambiguities; their lives and psyches are the arenas in which the larger battles take place. Security versus the need for self-expression; challenging a determined future with the risk of a second chance.

Some find satisfaction in their work, beyond paychecks, beyond prestige. They are the lucky ones -- or is it something in them? A Brooklyn fireman says, “I worked in a bank. You know, it’s just paper. It’s not real... But I can look back (now) and say, ‘I helped put out a fire. I helped save somebody. It shows something I did on this earth.’”

Terkel himself is one of these, though he calls it fortuitous. “I find some delight in my job as a radio broadcaster. I’m able to set my own pace, my own standards, and determine for myself the substance of each program. Some days are more sunny than others, some hours less astonishing than I’d hoped for; my occasional slovenliness infuriates me ... but it is, for better or worse, in my hands. I’d like to believe I’m the old-time cobbler, making the whole shoe. Though my weekends go by soon enough, I look toward Monday without a sigh.”

But there is no complacency. It is a danger “somewhat tempered by my awareness of what might have been. Chance encounters with old schoolmates are sobering experiences. Memories are dredged up of three traumatic years at law school. They were vaguely, though profoundly, unhappy times for me.” Of course, there is empathy here. But something more -- a willingness to learn. This was a difficult assignment. It concerned “the hard substance of the daily job” fused “to the haze of the daydream,” not only “what is” but “what may be.”

The conventional question-and-answer interview wouldn’t work here. Conditioned cliches could too easily come. “There were questions, of course. But they were casual in nature -- at the beginning: the kind you would ask while having a drink with someone; the kind he would ask you. The talk was idiomatic rather than academic. In short, it was conversation. In time, the sluice gates of damned-up hurts and dreams were opened. In nearly 600 pages, the words come out. “I was constantly astonished,” he writes and the reader will agree, “by the extraordinary dreams of ordinary people. No matter how bewildering the times, no matter how dissembling the official language, those we call ordinary are aware of a sense of personal worth -- or more often a lack of it -- in the work they do.”

The discontent is hardly concealed: “I’m a machine,” says the spot-welder. “I’m caged,” says the bank teller. “There is nothing to talk about,” the young accountant says. One must work. But there has to be something more. Mike Lefevre, a steel worker, says: “I’m a dying breed. A laborer. Strictly muscle work ... pick it up, put it down, pick it up, put it down ... You can’t take pride anymore. You remember when a guy could point to a house he built, how many logs he stacked. It’s hard to take pride in a bridge you’re never gonna cross.”

Some still find that meaning. A teacher, a policeman, a piano tuner. Some work to earn the privilege of living as they please: a hash slinger, a carpenter who is also a poet, a former nun who is still searching, a tree nursery attendant, once a quiz kid, who finds no tensions and pressures though work in a greenhouse is physically hard.

The work ethic which holds that labor is a good in itself is being questioned not so much for being a truism but for becoming distant from the reality of so many. Machines are taking over, people are unacknowledged. “The last place I worked,” says a bank teller,” I was let go. One of my friends stopped by and asked where I was at. They said, ‘She’s no longer with us.’ That’s all. I vanished.” Some bury themselves in work, serving their time. But others are in flight. Absenteeism flourishes. Others attempt to create their own excitement, pride themselves in the psychological manipulation of tippers. Occasionally they rebel. On the assembly line, they will let a car go by. “It’s more important to just stand there and rap. With us, it becomes a human thing.”

A human thing. The need to find significance takes odd expressions. Sometimes it is rebellion; sometimes pride; sometimes violence; sometimes fantasy. The quiet desperation gives way. The answering eloquence is in these pages. Things may increasingly make things but people remain and the greatest loss of the American dream may be our inability to recognize their significance in something more than banal platitudes.

If you have the intuition, the gut instinct that most people are better than their government, than the institutions which analyze them and project their lives, that they have a closer understanding of reality because that is where they are, “Working” is a book for you.

For the experiences here strike a chord. “I think most of us are looking for a calling, not a job,” say Nora Watson, a staff writer for an agency publishing health care literature. “Most of us, like the assembly line worker, have jobs that are too small for our spirit.”

ALSO:

Seamus Heaney, Nobel Prize-winning poet, has died

Randall Kennedy targets affirmative action in ‘For Discrimination’

Harlan Ellison, ‘happily 20th century,’ now has a YouTube channel

Carolyn Kellogg: Join me on Twitter, Facebook and Google+

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.