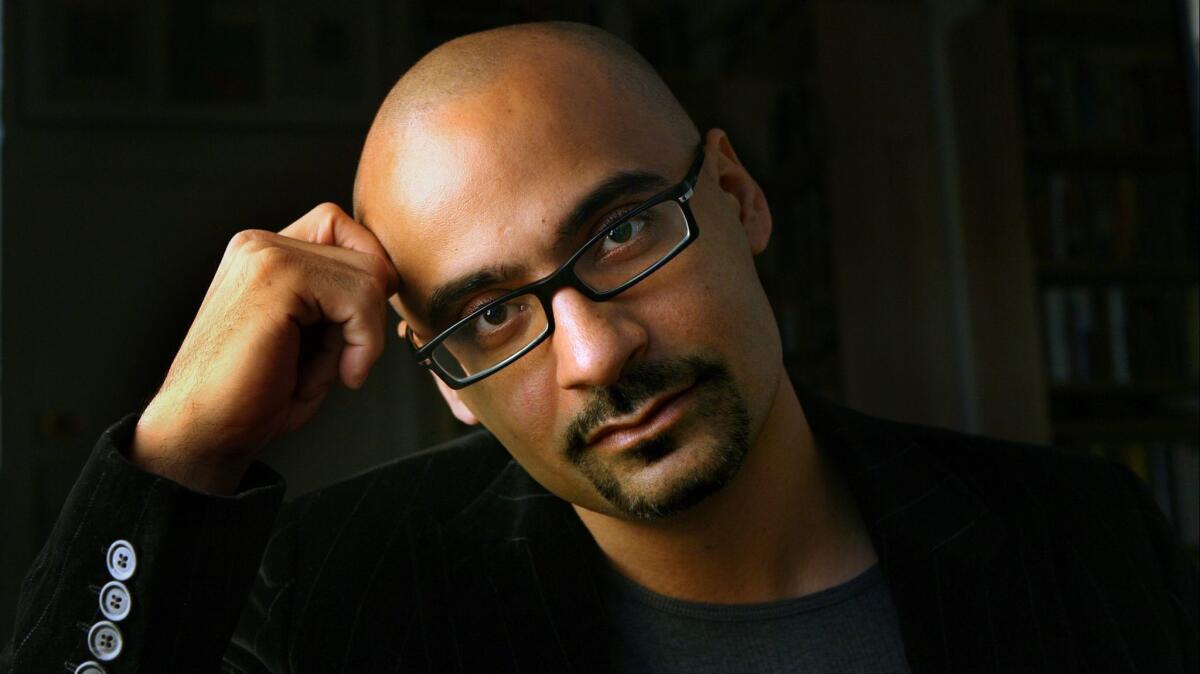

Q&A: Talking to Junot Díaz about ‘Islandborn,’ his first book for kids

- Share via

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Junot Díaz hasn’t forgotten where he came from — every book he’s written explores his origins in some way.

Although his family immigrated to New Jersey when he was 6, his memory of the Dominican Republic is strong. He remembers taking trips from Santo Domingo to his mother’s home province of Azua, located in the south of the Dominican Republic and as Díaz describes “closer to the primal, historical core of the island.”

“We would be in our family homestead up in the hills above the city and there would be no lights, no anything. I would stand outside my family’s little home and you would feel like you’ve been pressed right up against the face of the world,” recalls Díaz. “Heading out to the country, sitting around carafe lights, listening to my elders talk, the farmers talk about their day and their lives — it did a lot for me and it did a lot to me.”

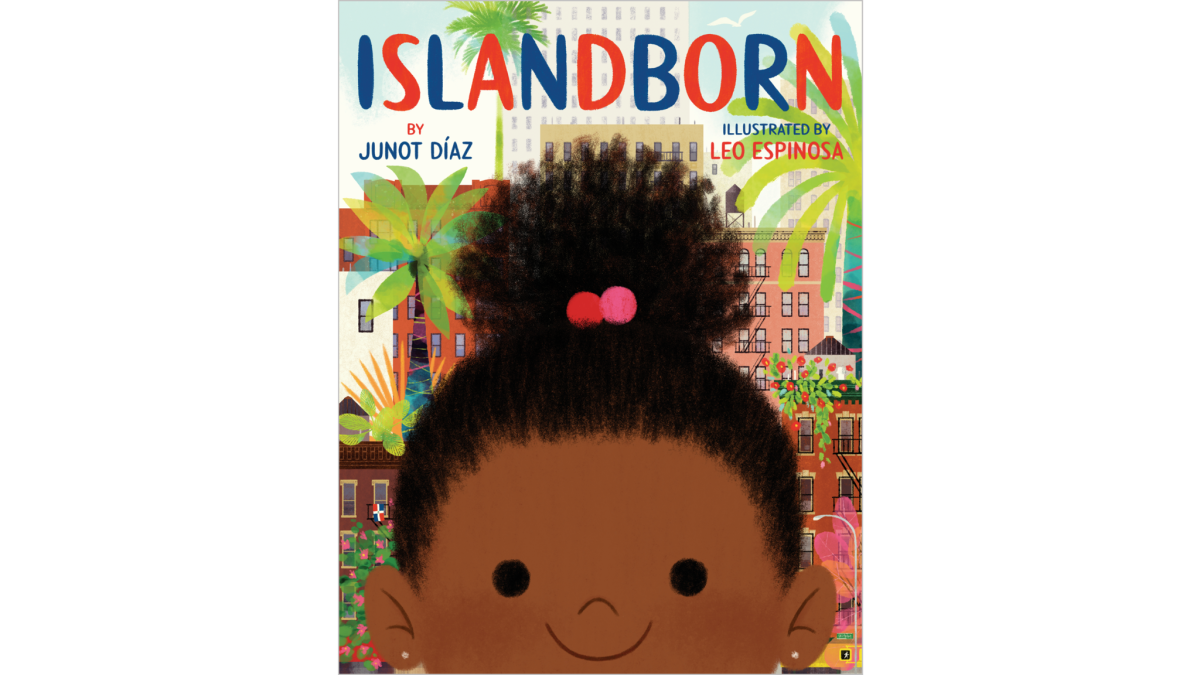

His new book is his first for children. In “Islandborn,” an Afro Caribbean girl named Lola is asked to draw a picture of her birthplace for a class assignment. Unlike her classmates, Lola left her first country too young to remember it. She goes on an imaginative adventure to collect and record memories from her family and neighbors with pencil and notebook in hand.

His childhood has been a prime topic of discussion during the tour, and like the fictional Lola who creates a book about her past, Díaz wrote a painfully honest essay in the New Yorker about his sexual abuse and what it means to unpack childhood trauma.

“I’d always assumed that if I ever returned to that place, that island where I’d been shipwrecked, I would never escape; I’d be dragged down and destroyed. And yet, irony of ironies, what awaited me on that island was not my destruction but nearly the opposite: my salvation,” writes Díaz about looking at his past.

His picture book is colorful, fantastical and filled with depth. At its core, it’s about looking at a community’s past to find a current sense of place and identity through the disarming sensibility of a child, unafraid to ask questions. Díaz spoke with The Times by phone, prior to the publication of his personal essay about his abuse, about his sources of inspiration, childhood and lack of representation. Our conversation has been edited.

The idea to write a children's book started when your goddaughters asked you to write a story about kids that looked like them, but that was almost two decades ago. Why write it now?

I kept returning to it. At least once a year I would stick my head into that corner of my brain and I couldn't come up with anything. It was a testament of my flawed imagination that every idea I had was either so preposterous or derivative that it wasn't even worth the time to flesh it out. What ends up happening is that you eventually get rid of so many bad ideas that a good one might wander into the space that you've carved out. I'm one of those writers who is so slow and bad at what I do that a lot of times my creative ethos seems to be you can't lose forever.

What were your goddaughters' reactions to reading "Islandborn"?

I do think that their reactions will unfold over a longer period of time. It's hard to unveil your heart even to someone that you've known and cared about for a long time. We are unfortunately in defended times, but they were very happy. They wrote me and spoke to me. They communicated their gratitude. My oldest goddaughter read the book while she was visiting. She read it the first time a few weeks before it was released. She closed the book and cried afterwards. It sort of broke my heart because I love her to death, but it speaks well to perhaps what it meant to her or what's been missing from so many of our lives.

Looking at how Lola and her neighborhood are illustrated brought up memories of wanting to have that representation, wanting to see someone who looked like me and the people around me when I was Lola's age.

That longing is yet to diminish in me.

Who were you envisioning when you were writing the book — your goddaughters or maybe yourself?

One uses oneself as an internal model, as a personal compass but one is also in conversation with people around you. Being an Afro Caribbean, an Afro Dominican, an Afro Latino, I've spent my life often in one way or another being sublimated, left out of account or being slotted into the wrong communities — dismissed and blighted and erased. There are a lot of us who have these similar experiences where our complexity, our multiplicity are not welcome. So many of my friends struggled with these questions and difficulties. I was thinking of them and I was thinking of people in my community who shared similar tribulations. I was also thinking of the children of my friends. Many of them are little Lolas who are growing up in a different place and time with parents creating and nourishing healthier spaces. Lola is not me. Lola is a child from a different generation. Lola is growing up far more loved and better supported than I was.

Did you, like Lola, collect memories from others about the Dominican Republic?

No child doesn't attempt to explore his or her origins. All children are assemblages from the stories that they hear around them. For immigrants, it becomes more pressing. It's not just the past. It becomes politically, socially and symbolically charged. On the other hand, I had the fortune of actually having experiences and strong memories of the Dominican Republic. I also have siblings who did not have any memories of the Dominican Republic. Between those in the family who had tactile archives in Santo Domingo and those who did not — that is also part of the experience of this book. I always wondered about my little sister who couldn't remember Santo Domingo at all, what it must mean for her to maintain a strong relationship with the island as opposed to me. Could I have had more memories? Of course. If I had come over at 12, it would be different than if I had come over at 6. But what we discover is not that the quantities of the memories matter, but what one makes of them. I know people who have lived in Santo Domingo for 30 years who have never looked back.

Lola's island seems to be the Dominican Republic, but the island is never named. There is an island monster, never explicitly named as Rafael Trujillo's dictatorship. Why?

I'm not so sure that the island, of which the Dominican Republic takes up one portion, is Lola's island. Part of what makes the book interesting for me is that it is both the Dominican Republic, both Hispaniola and not Hispaniola. There are plenty of visual clues that this is the Dominican Republic, but there is also plenty of space for someone to read the book and to come to the conclusion that this is actually a place that doesn't exist. This is not our world. We are in an adjacent reality, which was really part of the project.

It wouldn't have cost me anything to name the island the Dominican Republic. I've never had any problems being exquisitely specific in my books. In fact, I’ve believed in the specific door to the universal. This was not an effort to generalize in hoping to make more space for readers. In fact, it was about the journey that Lola goes on. Lola, in some ways, is encouraged to create a relationship with the place that she has never really known. If I'm asking Lola to engage in such imaginative courage, then I think it would be only logical if the reader had to participate. There is an opportunity, there is an invitation for the reader to mirror Lola's journey. That this island is actually a place that they have never been to either and they could never go to because it is not a real place in our world. I thought that was very important.

Now, that was high order and 99% of the readers will neither be interested in it nor will they find that a satisfying game, but I enjoyed the game. So I built it into the book.

There's also this sense of melancholy and doom in some of the memories that Lola collects. Did you have any second thoughts about incorporating these darker parts into a children's book?

I don't believe children are not aware that something is up with the incomplete stories that adults tell. I, as a young person, knew something was amiss in the narrative my family reproduced. I could sense the gaps and the silences strongly. What they were trying to hide from us poured out in the silences anyway because we were not spared anything. We were not spared the anxiety, the loss. We were not spared the agony. We were just denied names and a way to engage it that would be empowering. I think the exact opposite. I think that we do a grave disservice to young people by condescending and hiding from them that which they can already sense. For me, it was more important to give someone like Lola the tools and the community and the guidance with which she can face what was already present in her life. There's different ways and different strategies, which we render what is traumatic in our histories. It matters quite a lot to me that the strategy for this book would be something that would leave Lola with a sense of her own possibilities, with a sense of her own agency, with a history of her family and community' heroic resilience.

I definitely felt those gaps and silences in my family story. I wish I knew how to dig deeper back then. As a kid, you feel things but you don't have the words or context to make sense of any of it.

That's the great trick. Your childhood never stops. The opportunity to dig we will often take up as adults. Therefore, we will do for our childhood selves what we were not able to do and that matters quite a bit. There is no time limit in recovery and recuperation.

You've said that you didn't read children's books growing up. When did you start reading and when did your love for reading develop?

I've always loved books as soon as I got my hands on them when I came to the United States. I was 6 years old. The problem was I couldn't read a word of English. I didn't really get a handle on it for a little while. By the time I could read, I was already reading at a level that exceeded picture books. I read chapter books. That's part of this too. The fact that I didn't have this experience. That I would look at the other kids around me and they all had these relationships to these picture books that I never had. Certainly that was part of my motivation to live in picture books for a while.

Did you read children’s books when working on "Islandborn"?

I was trying to read absolutely everything. But the people that have the biggest impact on me — it was a book called "The Journey" by Francesca Sanna. There was Edwidge Danticat's "Mama's Nightingale," which just killed me. It taught me a lot of valuable lessons about how you can tell a story with tough beings in a lovely way. There was of course, more or less anything that Jacqueline Woodson wrote. Jacqueline Woodson is extraordinary. Those are in some ways my compass points. They really showed me the way.

Were you listening to any music while writing the book?

Always. I'm not a musician. I don't make my life in music. Some people music is their air. Books have been my air. Music has been my bread, which is significant. The thing is — this is a bit shame-faced. I grew up listening to real ratchet hip-hop and I continue to listen to real ratchet hip-hop. There is also my love of bachata. That is always on high rotation.

The book came out in early March; what kinds of responses have you gotten from kids?

Well shoot, you know how kids are. There are a lot of ages. Some of them are there because their parents are taking them to expose them to a literary event, to expose them to another Caribbean. There are kids where it's a bit of a party. They run around. It's fun as hell. Throw balloons at me. Some kids are older and their parents and caretakers are taking them for similar reasons. Kids enjoy one way or another being out in the world and having that space. But whether that is just about me would be really up to debate.

What were conversations like when you were talking about the cover and illustrations?

My notes were very strict. I'm pretty much a relaxed collaborator except when it comes to matters of representation. Matters of getting correct of who my little Afro Caribbean girl was and is. Lola is my little morenita. I needed to be sure that she and her family, her community and her friends were faithfully engaged with. One thing I had going for me is that I had Leo Espinoza, another Caribbean and someone who understands really well what is at stake, who understands really well Caribbean bodies, Caribbean hair, Caribbean expressions, Caribbean gestures, Caribbean color, Caribbean soul. That mattered to me immensely. Even though I gave Leo some guidance, the truth of the matter was that Leo didn't need much at all from me. In some way, I gestured in the general direction and before I knew it Leo had constructed a wonderland.

I noticed the details of the characters' hair and hairstyles right away — Lola's hair, her classmates' fades, the cornrows.

It's deeply satisfying, believe me. Normally, about my own books I'm always circumspect. God knows I don't know anything about what they mean or how they matter, but when it comes to Leo Espinoza's illustration I can confidently say that they’re absolutely a gift. A gift. A gift. A gift. I'm just lucky to have someone like that as my collaborator. He did long labor to bring this world to light.

Talk to me about your choice in author photo.

That was just a lark. We were all like hey, let's get our kid’s photo up.

When was that photo taken of you?

That photo was from my passport to come to the United States.

Junot Díaz will be at the Festival of Books reading from “Islandborn” at the Reading by 9 children’s stage at 4 p.m. April 21 and in conversation with The Times’ Carolina Miranda on April 22 at 10:30 a.m. in Bovard Auditorium.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.