AeroVironment draws on high-altitude drone development to help make a helicopter for Mars

- Share via

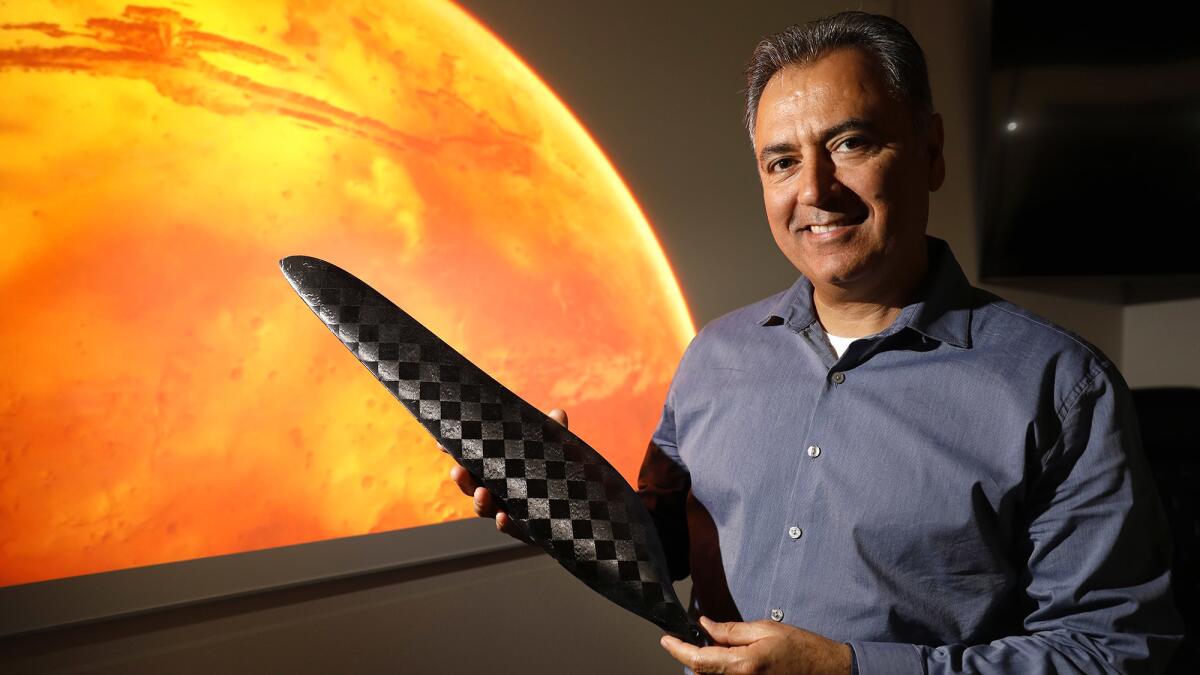

A Southern California company that specializes in small drones for the military has an opportunity to contribute to aviation history: the first aerial flight on Mars.

AeroVironment Inc. is making the rotors, landing gear and material to hold solar panels for the Mars Helicopter project, which will be assembled at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. The device will deploy from NASA’s latest Mars rover in 2020, taking high-resolution images that can determine where the slower-wheeled vehicle should head next.

The drone helicopter will look somewhat similar to a hobbyist device you might see whiz by on the beach. But it will incorporate years of research into the challenges of flying in a thin atmosphere that has similar density to about 100,000 feet above Earth’s sea level.

“There’s been a lot of doubts about being able to even fly in the atmosphere of Mars,” said Wahid Nawabi, chief executive of the Monrovia-based company. “It’s been over 100 years since the Kitty Hawk moment. This is the next event.”

The four-pound drone’s lithium-ion batteries will be charged using solar panels, allowing it to deploy as far as 328 feet from the rover. Its four-bladed rotors will each measure about four feet in diameter and will spin at 2,300 to 2,900 revolutions per minute, about 10 times the rate of a helicopter on Earth, according to JPL. The blades will consist of a foam core overlaid with carbon-fiber composites to keep them lightweight but strong.

JPL is building the drone’s fuselage, which includes the battery system, circuit boards with built-in computers, cameras, altitude-measuring devices and other sensors.

JPL and NASA initially began researching the feasibility of flight on Mars back in the 1990s. Engineers eventually determined there was enough air to lift a vehicle on the red planet, but the vehicle would have to be light and its propellers would need to spin very fast, said MiMi Aung, Mars Helicopter project manager at JPL. At the time, computing, battery, composite material and solar-cell technology were not advanced enough to move forward.

Eventually, drone reconnaissance could be used to assist human exploration of Mars, she said.

“Having something fly 10 to 40 meters above ground will give you a totally different vantage point,” Aung said. “There are very interesting scientific areas of interest ... you can’t get to with astronauts on foot or rovers.”

AeroVironment, whose military reconnaissance drones go by names like the Puma, Raven and Wasp, is developing its portion of the Mars Helicopter with a small team at its Simi Valley production facilities.

Over the years, AeroVironment has worked on several high-altitude drones, including the Pathfinder Plus remotely piloted aircraft. Developed under a NASA program, the solar-powered drone had a wingspan of 121 feet and flew higher than 80,000 feet and was retired after a final mission measuring atmospheric turbulence in 2005. The company also worked on a high-altitude, long-endurance, solar-electric-powered prototype drone called Helios, which broke a world altitude record for sustained level flight in 2001 by reaching 96,863 feet.

Helios was the precursor to a liquid hydrogen-powered drone called Global Observer, which had a 175-foot composite wing and was designed to cover 280,000 square miles at a time for reconnaissance or communications purposes.

“There have been a number of breakthroughs in battery technology and solar technology that really appear to enable high-altitude, long solar systems to become a reality,” said Philip Finnegan, director of corporate analysis at market research firm Teal Group. “If [drones] stay up for months on end, it means a lot of what happens can be done automatically so there’s less manpower needed, fuel costs go down, operating costs go down.”

More recently, AeroVironment announced a joint venture with Japanese conglomerate SoftBank Corp. to develop a high-altitude, long-endurance solar drone that would function as a “pseudo-satellite” for commercial purposes, according to a company statement in January. Nawabi said the company’s work on the Mars Helicopter, and its previous experience in this field, helped it land the SoftBank joint partnership, whose development contract has a net value of more than $70 million.

Compared with the SoftBank joint venture, the Mars Helicopter is a “fairly small project,” Nawabi said. Neither AeroVironment nor NASA would give the value of the contract.

Twitter: @smasunaga

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.