Fateful Days Ahead for Enron’s Lay, Skilling

- Share via

If the Enron Corp. fraud trial were a pay-per-view event, its big-money days would be just ahead.

With their freedom on the line, former Enron top executives Kenneth L. Lay and Jeffrey K. Skilling soon will take the witness stand to try to persuade a federal jury that they didn’t lie and cheat to protect the riches they had amassed in Enron stock. The importance of their testimony can be put simply, said Houston trial lawyer Kent A. Schaffer: “If these guys are bad witnesses, they’re going to prison.”

Skilling, Enron’s former chief executive, is expected to take the stand around April 12 or 13, and Lay, the energy-trading company’s founder and former chairman, shortly thereafter.

The two face multiple counts of conspiracy and fraud that could land them behind bars for more than 20 years. Skilling also faces charges of insider trading.

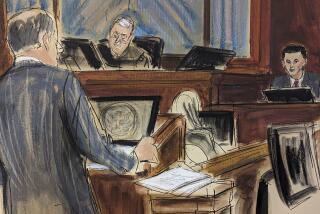

After the government rested its case Tuesday, U.S. District Judge Sim Lake jokingly declared “spring break” and granted the defense’s request for a pause until today to call its first witness. In return, Lake urged the defense to trim its presentation to four weeks from six and try to get the case to the jury of eight women and four men by the end of April.

The government presented 22 witnesses over nine weeks. The thrust of their testimony was that Skilling, 52, and Lay, 63, participated in efforts to manipulate the company’s reported earnings and repeatedly lied to the public about its financial condition.

Daniel M. Petrocelli, Skilling’s lead lawyer, called the case presented by the Department of Justice’s elite Enron Task Force “short on specifics.”

“If you asked the jury to deliberate today, I doubt if they could reach a clear-cut decision,” he said in an interview last week.

“We’re in very good shape right now, with the task force having done their worst,” echoed Michael W. Ramsey, Lay’s head lawyer. Ramsey, 66, added that he was feeling great a few days after undergoing an emergency procedure to correct a small blockage in a coronary vessel.

Outside legal experts believe that Skilling and Lay face an uphill climb.

Nashville lawyer Gary M. Brown, former counsel to a Senate panel that investigated Enron, said the prosecution kept its case fairly simple, considering that it had to explain arcana such as off-balance-sheet financial structures that the government alleges were used to hide losses or falsely inflate profit.

He said the parade of government witnesses who had pleaded guilty to Enron-related crimes made it tougher for the defense to argue that the only wrongdoing at Enron was the secret thievery by former Chief Financial Officer Andrew S. Fastow and a few accomplices.

“Everything Enron did was legal?” Brown said. “That’s not going to fly.”

Lay and Skilling’s lawyers maintain that Enron’s 2001 bankruptcy was precipitated not by a massive conspiracy but a crisis of confidence -- akin to a run on the bank -- on the part of Enron’s trading partners, who were spooked in part by media reports about the fraud involving Fastow.

It’s a difficult story to put across, Schaffer said, which is why Lay and Skilling’s testimony is “crucial for any chance of acquittal.”

Lay may be an effective witness, Schaffer said, because he was the sort of boss who would chat with low-ranking employees on the elevator. “People like him,” Schaffer said. “That’s what you want in a witness.”

Skilling, by contrast, had a reputation as being aloof from subordinates and -- as the jury heard from several witnesses -- prone to dressing people down in profane language.

But he also is bright and articulate and could perform well on the stand, Schaffer said, providing that “he doesn’t get testy or condescending.”

A problem for Skilling, several legal observers said, is that, unlike Lay, he has testified under oath before Congress and the Securities and Exchange Commission, and those statements could be used to contradict what he says on the stand.

Prosecutors took aim at one such assertion March 27. Skilling, according to transcripts shown at trial, told SEC investigators that he had sold 500,000 shares of Enron stock on Sept. 17, 2001, solely because he was worried about how the World Trade Center attacks would affect the economy.

But stockbroker Glenn Ray testified that Skilling had attempted to sell 200,000 Enron shares a week before 9/11. The sale didn’t go through because the brokerage required proof that Skilling -- who had abruptly resigned as Enron CEO three weeks earlier -- was no longer a company officer and thus not subject to trading restrictions.

Skilling believes he can justify his behavior and is eager to testify, he said in an interview on the eve of the trial.

Before putting Skilling and Lay on the stand, the defense wants to repeat a message that it delivered in opening arguments and cross-examination: The case is largely about government coercion.

The opening defense witness, Joannie Williamson, is a close friend of prosecution witness Mark E. Koenig, Enron’s former investor relations chief. She is expected to testify that Koenig confided to her in December that he was innocent and had been arm-twisted into cooperating with prosecutors. Koenig, under cross-examination, denied having said that.

Not only did several such witnesses plead guilty to crimes they didn’t commit, Ramsey said, but potentially exculpatory witnesses have been scared away by fear of future indictments.

“They’re afraid to come outdoors,” he said.

Despite that handicap, Ramsey was confident. “We get the ball in the second half,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.