Bingo Hall Strife Grows in Hawaiian Gardens

- Share via

To the extent most people are even dimly aware of the Hawaiian Gardens Casino, it’s probably from the card club’s garish sign, which looms over the 605 Freeway like a giant neon basilisk.

Members of the state Gambling Control Commission, which will consider the casino’s application for a permanent license at its meeting today, probably wish the club’s public profile ended there.

Instead, state officials have observed that the Hawaiian Gardens licensing process has been the most contentious they’ve faced in the commission’s three-year existence.

There’s been name-calling, allegations of fraud and extortion, outbursts of emotion at two hearings the commission recently convened in Los Angeles.

And it all boils down to this: Is it wise for the state to give Dr. Irving I. Moskowitz an opportunity to print more money?

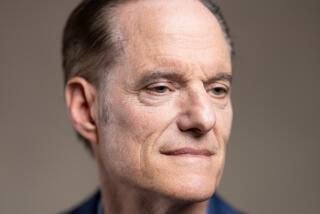

Moskowitz, 75, is the owner of the card club and, through his personal foundation, of the charity bingo hall next door. (The casino operates under a provisional license, pending a commission vote.)

A retired obstetrician now living in Miami Beach, he’s famous in two places on Earth -- in Hawaiian Gardens, and in Israel, where he has funneled millions of dollars into causes that include buying up land in Arab neighborhoods of Jerusalem and turning them over to Jewish settler groups.

The practice, which inflames local tensions, reflects his conviction that any compromise by Israel with its Arab and Palestinian neighbors is tantamount to a suicide pact.

The money for these efforts comes from the bingo hall, which brought in $26.3 million in revenue in 2001, the latest year for which the Moskowitz Foundation’s public tax return is available. Out of that sum Moskowitz made $3.6 million in grants, of which about $530,000 went to Hawaiian Gardens community groups (mostly to a food bank he controls). Most of the rest went to Jewish and Israeli organizations.

In Hawaiian Gardens, meanwhile, the Moskowitz story is a lesson in what can happen when one person acquires so much money and power in a tiny, destitute place that his shadow falls over everything and everybody.

Whether Moskowitz is as venal, vindictive and manipulative an individual as his enemies paint him, or whether he’s the savior of Hawaiian Gardens -- that’s the view of the city’s current leadership, who benefit from the $6-million annual income from the card club that provides 75% of their budget -- has never been established by a public, objective investigation.

It’s conceivable that a licensing report by the attorney general’s division of gambling control, which has recommended approval, has settled the question.

But the report hasn’t yet been made public, so it’s unclear whether it lays to rest decades of opponents’ allegations of political chicanery and financial misdeeds.

“He’s had a very corrupting influence on the city government,” said Haim Beliak, a Los Angeles rabbi who heads the anti-Moskowitz Coalition for Justice in Hawaiian Gardens and Jerusalem. “The state has failed in its responsibility to enforce the law.”

Moskowitz’s attorney and spokesman, Beryl Weiner, dismisses the casino opponents as owners of competing card clubs or people motivated more by opposition to Moskowitz’s political and religious beliefs than to his activities in Hawaiian Gardens.

“Rabbi Beliak and his minions decided that Dr. Moskowitz is solely responsible for the fact that there’s not peace in Israel,” Weiner says. “A lot has been passed off as fact, but it just ain’t so.”

The very founding of the Hawaiian Gardens card club is enveloped in controversy. Moskowitz was granted the land in 1993 by the city’s redevelopment agency, apparently on the expectation that he would develop a supermarket on the blighted parcel. Instead, within two years -- allegedly at Moskowitz’s behest -- the city administration scheduled a public referendum to allow a casino on the site. Moskowitz funded the successful pro-casino campaign with more than $540,000 of his own money.

Various complaints that this process was crooked led to an investigation by a joint legislative audit committee in 2000. The committee staff said it found evidence that the redevelopment terms violated state law and that Moskowitz, through litigation, delay, pressure and sheer coziness with politicians, had managed the process to benefit himself.

The staff also aired allegations that Moskowitz and his agents manipulated the city government by threatening to cut off payments from the bingo hall that were critical to the funding of the tiny city’s police force and other services. It noted, furthermore, that he had funded a recall campaign against two city officials who had tried to thwart his plans.

Weiner calls the legislative report a one-sided screed concocted by Moskowitz’s enemies. He says Moskowitz financed the pro-gambling campaign because competing club owners opposing the measure were spreading misinformation.

He acknowledged that Moskowitz contributed money to the recall campaign, but said the voters were fed up with its targets anyway. And he noted that the city budget would be in the red by millions of dollars a year if the card club had been blocked.

But there are questions about Moskowitz’s business activities that the report didn’t even broach.

Consider, for example, the relationship between Dr. Moskowitz and Tri-City Regional Medical Center, a supposedly independent Hawaiian Gardens hospital that acquired a federal tax exemption in 1997 by intimating to the IRS that it would devote at least some of its resources to local community services or charity care.

The hospital is the successor (following a couple of intermediate corporate transfers) to a facility Moskowitz built in 1970 and operated on the Pioneer Boulevard site for 10 years. He still owns the building and land, for which he charges Tri-City rent.

Moskowitz’s opponents suggest that he remains the financial power behind Tri-City and that the tax exemption is his way of maximizing his return without the “inconvenience” of state and federal taxes.

Moskowitz’s lawyer, Weiner, says the doctor has “no relationship” with Tri-City “except with respect to his company being its landlord.”

On the other hand, the hospital’s lawyer -- Beryl Weiner -- acknowledges that the Moskowitz Foundation also helped launch the tax-exempt institution in 1997 by loaning it nearly $5 million. The loan remains outstanding. Also outstanding, Weiner says, is a $3.5-million loan from Moskowitz’s company to finance the hospital’s acquisition of equipment.

A key issue is whether Tri-City really deserves nonprofit status, which tax experts say should normally go to institutions devoted exclusively or substantially to charity work. Although Tri-City, in applying for its exemption, supported its claim to be concerned with charitable works by telling the IRS that it would solicit grants from charitable institutions and government agencies and would develop a fundraising apparatus, it has never received a dime in charitable grants or spent a dime on fundraising.

Tri-City’s state health department financial profile for 2002, the latest year available, further states that it spent absolutely nothing on “uncompensated charity” costs that year, other than on bad debts, which the IRS normally doesn’t count in the charity category. The Tri-City profile also acknowledges it’s not eligible for state “disproportionate share” grants, which go to healthcare providers heavily involved in treating the indigent.

Wiener says the hospital did receive more than $1.5 million in federal Medicare disproportionate share money in 2002. But that’s out of gross revenue of $102 million. He also says the hospital “meets all the tests” for tax-exempt status and that it has been audited by the IRS. He refused to say when that audit was, however.

Maybe the attorney general’s investigators have gotten to the bottom of all this. If not, they may still have some time. The fight over Irving Moskowitz is so complex and deeply rooted in history that the state gaming commission is expected to do no more today than to receive a status report from its staff and table the license for a later time.

*

Golden State appears every Monday and Thursday. You can reach Michael Hiltzik at golden.state@latimes.com and read his previous columns at latimes.com/hiltzik.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.