Nasdaq hits 5,000 for the first time since 2000

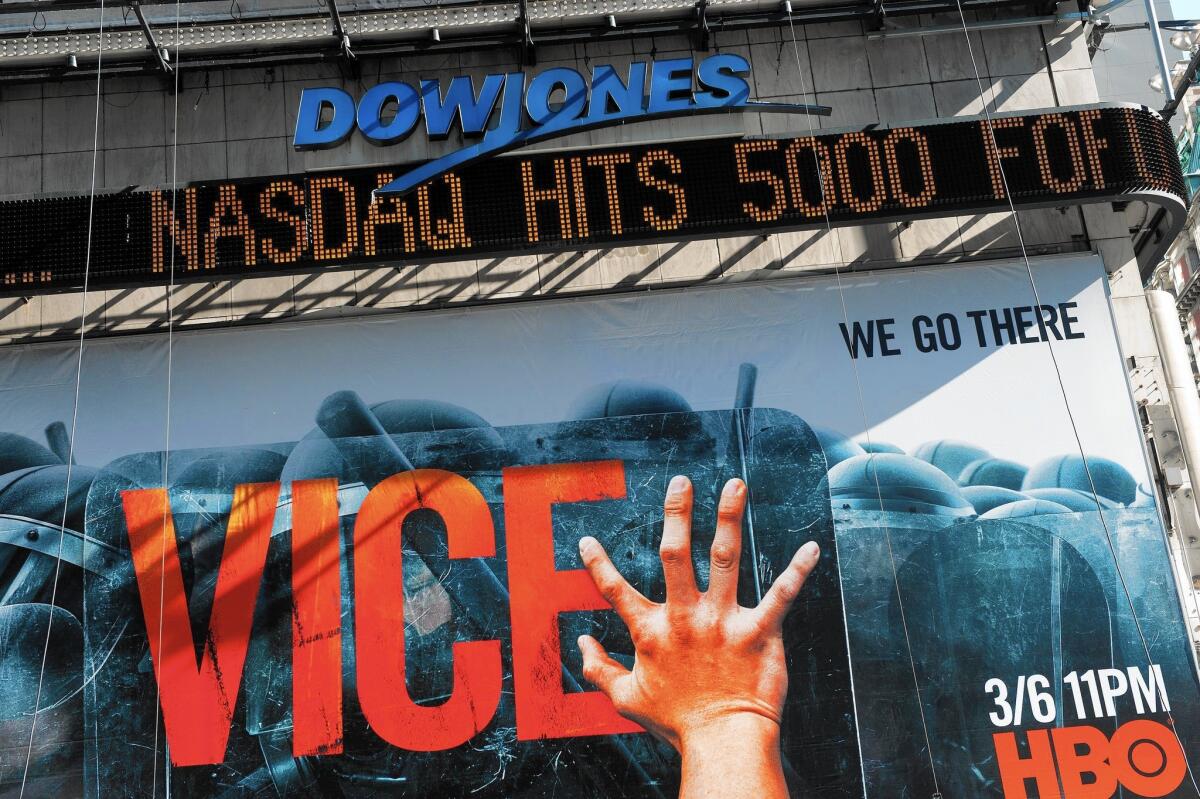

The Nasdaq index is only a short distance from its record close of 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000. Above, the Times Square news-ticker announces the milestone Monday.

- Share via

The Nasdaq hit 5,000 again. Time to head for the hills, right?

Maybe not this time.

The technology-heavy Nasdaq composite index nudged through the symbolic point barrier for the first time since March 2000, shortly before what was known as the dot-com bubble burst in a dramatic collapse.

The steady climb, to 5,008.10 on Monday, was far more gradual, and the underlying fundamentals much more sound than the first time around, analysts said.

Amid the euphoria of the dot-com era when the Web was fairly new and the Internet promised boundless opportunity, stock prices became untethered from profits — even revenues — in the belief that the Internet would so transform the economy that conventional valuation metrics would be rendered obsolete.

“It doesn’t resemble the speculative excesses that were in effect when it last set a record high,” said John Lonski, chief capital markets economist at Moody’s Analytics.

At the bubble’s peak, key components of the Nasdaq index traded at more than 50 times future earnings, Lonski said, calling them “nosebleed” levels. And the broader index traded even higher.

The market for initial public offerings then was the boom’s primary pump. As new stocks such as Yahoo Inc. rocketed up with no end in sight, a speculative frenzy took hold. Those who missed Yahoo wanted in on the next IPO.

The craze hit a peak with the Dec. 9, 1999, IPO of VA Linux Systems, a Sunnyvale, Calif., company that sold computers geared to run the Linux operating system.

The company had set its opening price at $30 a share. On its first day, shares climbed to $239, which defied rational explanation even among tech-stock boosters. The crash came the following spring. By September 2000, VA Linux stock traded at $8.49.

Today’s market, however, is underpinned by the likes of Apple Inc., whose market value of $748 billion accounts for more than 10% of the Nasdaq’s composite valuation. Meantime, companies such as Facebook Inc. and Google Inc. are enjoying strong earnings, at least for now.

The Nasdaq’s price-to-earnings ratio, a key measure of a stock’s value, is about 18 times estimated future earnings, said Lonski, who called it well within levels considered sustainable.

The Nasdaq index is only a short distance from its record close of 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000. Should it break that level, it would join the blue-chip Dow Jones industrial average and the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, both of which have hit new highs often over the last year.

On Monday, they did so again. The Dow rose 0.9% to 18,288.63; the S&P 0.6% to 2,117.39. Nasdaq added 44.57 points, or 0.9%.

Analysts said the rise of all three major U.S. indexes, as well as markets overseas, was partly the result of broader macroeconomic news, including the announcement of an interest rate cut by the Chinese central bank and reports of strengthening in the U.S. labor markets.

California companies wield a strong influence on Nasdaq: Seven companies based in the state are among the top 10 Nasdaq-listed companies, by valuation.

Although there are risks to the tech-heavy index, analysts said, they lie mainly in the broader economy — economic stagnation in Europe, a slowdown in China, a highly valued dollar hurting exports — the same things that haunt stocks in general. And even the risks specific to the Nasdaq don’t resemble those that doomed the market 15 years ago.

A big difference this time is the public’s overwhelming embrace of technology — from broadband use, online shopping, smartphone penetration and the rapid adoption of mobile technology — and its demonstrated willingness to devote a significant portion of the household budget to it.

“There are credible penetration and usage scenarios that exist now that just weren’t there 15 years back,” said Sameet Sinha, a senior Internet analyst with San Francisco-based B. Riley & Co.

Another difference is the state of financial markets themselves.

The dot-com era was marked by freewheeling practices on Wall Street that saw the breakdown of traditional barriers between stock analysts issuing buy-and-sell recommendations to the public and investment bankers trying to win business from the same companies.

After the tech wreck, analyst research underwent sweeping reforms under an industrywide settlement to end an investigation into fraudulent stock research led by then-New York Atty. Gen. Eliot Spitzer.

The current market has been driven less by hype and speculation about future innovation than conventional profit measures. Companies that go public now tend to be more mature, so retail investors are less likely to get burned on individual IPOs.

Sinha said that even dot-com mainstays, such as Hewlett-Packard Co., Sun Microsystems Inc. and Dell Computer Corp., had relatively low profit margins, while some of the most extravagantly valued Internet companies had no profits at all.

Amazon.com Inc. notably had no profits for years. By contrast, Sinha said, Nasdaq pillars such as Google and Facebook Inc. report profit margins around a stunning 50%.

They have a hammerlock on their markets, gained largely through consumer popularity, but that is a risk in itself since, historically, such dominance has invited either regulatory intervention or, more frequently, the rise of upstarts more than happy to compete at lower margins.

“There’s no way margins like that are sustainable” over the long term, Sinha said.

But for now, analysts said, the tech sector looks relatively attractive compared with other parts of the U.S. economy as the recovery from the Great Recession heads toward its seventh year and share prices across the board reach relatively high levels.

“Technology stocks have been buoyed by good earnings and still have some way to go, given that that they represent a growth sector as the economic cycle matures,” Russ Koesterich, global chief investment strategist for investment management giant Blackrock Inc., said in a note Monday.

One thing going in their favor, he wrote, is cash.

Just four companies — Apple, Google, Cisco Systems Inc. and Microsoft Corp., all Nasdaq components —have more than $360 billion in cash and marketable securities on their balance sheets, almost a quarter of the total of corporate cash reserves in the U.S.

Of all the differences between today and the dot-com era, that might be the starkest.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.