Russia’s wheat woes could hit U.S. grocery shelves

- Share via

Reporting from Los Angeles and Moscow — The price of America’s daily bread and meat could soar this fall, as surging wheat prices in anticipation of a Russian ban on exports stoked fears about tight supplies.

Grain shortages and food price hikes in 2007 and 2008 sparked riots worldwide, but agriculture analysts said the U.S. wheat crop has been strong, and that stockpiles of wheat and other grains worldwide are greater now than they were three years ago.

According to media reports, U.S. farmers have rushed to put out millions of bushels of wheat to bolster worldwide inventories. Wheat prices on Friday dropped by 60 cents on the Chicago Board of Trade, voiding Thursday’s price run-up.

Yet analysts warned that consumers might be hit with higher prices at the grocery store in the months ahead because of a convergence of factors. With the memory of the previous food crisis still fresh, some countries and consumers may resort to hoarding, which could push prices upward. Speculators and some food companies might seek to exploit public worries.

“The situation is still in flux,” said Phil Flynn, a commodities analyst at PFG Best in Chicago. “It is far too soon to say that this is over.”

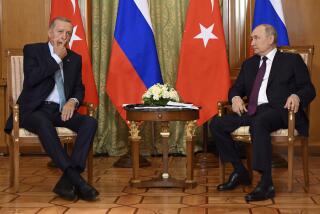

The price of wheat surged to a two-year high when Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin announced the ban Thursday. Wildfires and serious droughts have ravaged a large swath of central Russia this summer, destroying one-fifth of its crop. Russia is one of the world’s largest wheat exporters.

The Ukraine government, also a large global wheat supplier, reportedly canceled a number of its contracts because of similar dry-weather issues.

Russian officials quickly backpedaled from their earlier firm stance that the export ban would begin Aug. 15 and last through the end of the year.

On Friday, Igor Shuvalov, Russia’s first deputy prime minister, said the government would honor current contracts and might revisit the ban later this year. The country, according to media reports, is considering whether to delay the ban until Sept. 1, to let at least 700,000 tons of grain shipments already en route to leave the country.

Government officials acknowledged that it was still unclear whether the drought would stretch into the fall, when farmers would be gearing up to plant next year’s crop. Shuvalov also said that the government didn’t know how much grain it would ultimately be able to harvest in the fall.

The country had been expected to produce 80 million to 85 million tons of grain this year, according to Russian agricultural experts.

They said Russia now would be lucky to turn out 75 million tons this season.

“Our main responsibility is to provide people with basic foodstuffs,” Shuvalov said Friday in an interview with radio station Echo of Moscow. “And then we will certainly fulfill our export obligations.”

He added, “If we have a surplus [of grain], then exports will be renewed.”

In some ways, the run-up in wheat prices makes little sense, said Jay O’Neil, a senior agricultural economist with Kansas State University’s International Grains Program.

The U.S. has enjoyed a bumper crop this year and, at least until recently, reports of global wheat stockpiles have remained high.

“The world is awash in feed grains,” O’Neil said. “This is silly. These grain prices shouldn’t be this high.”

Yet prices of these crops — a staple for many cultures and the basis of livestock feed — have been rising steadily, driven in part by speculation by investors and financiers. Soybeans started the rise earlier this year, O’Neil said. China, faced with a burgeoning middle class with expendable income and a hunger for protein-rich meals, increased its demand for U.S. exports of soybeans for cooking oil and animal feed this year.

Then, this summer, for the first time in more than a decade, China placed orders for U.S. corn — a reported 750,000 metric tons — and ships have started delivering it to the country’s eastern coast.

“As prices rose on corn and soybeans, wheat floated up with it,” O’Neil said.

But wheat has outpaced the other grains, amid dark portents of the year’s harvest. Australia’s stockpiles were healthy, but its fields suffered from below-average rainfall and a locust plague. Dry weather is hampering fields in Kazakhstan and the European Union.

In the last two months, wheat prices have nearly doubled in Chicago.

On Friday, wheat prices closed at $7.2575 a bushel, down 60 cents. Corn closed at $4.05 a bushel, up 1.5 cents, and soybeans were $10.59 a bushel, up 4 cents.

The hope that Russia may ease back on its wheat ban offered little solace to some world leaders, who still recall the painful memories of grain shortages, rising prices and deadly food riots in 2007 and 2008.

Media reports this week said the Indian government has been aggressively stockpiling wheat, hoarding piles underneath tarps where the grain has started to rot.

Food retailers in Switzerland and England warned consumers Thursday to prepare for higher prices on bread, cereal and beer.

Egypt, which gets at least 50% of its wheat supply from Russia, is also worried. The Ministry of Trade and Industry said prices of imported wheat recently jumped by 46% in one month.

The prices of wheat, bread and other grain products in local markets have also increased. Officials rushed to assure the public that Egypt had a four-month supply of the grain on hand.

Some of the country’s worst riots of the last 50 years broke out in the 1970s, when then-President Anwar Sadat attempted to cut bread subsidies. (The violence forced him to repeal the plan.)

Amid worldwide shortages in 2007, demonstrations broke out at bakeries across the country and several people were killed in fights over bread.

“Wheat is such a crucial product for Egyptians’ daily life and people won’t be able to live with massive increases of wheat prices or any shortages,” said Tawfik Habbal, a commodities expert in Cairo.

Special correspondent Amro Hassan in Cairo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.