Review: Tentative signs of progress in Metro’s transit network design

- Share via

For two decades, and especially since voters approved a $40-billion transit tax in 2008, the L.A. County Metropolitan Transportation Authority has ranked among the most important patrons of public architecture in Southern California.

It has often seemed remarkably ill-suited for the role, burying architects and planners near the bottom of its bureaucratic hierarchy and turning out an uninspired collection of subway and light-rail stations.

But there are signs of a new respect for architecture at Metro: With the Los Angeles firm Johnson Fain, the agency is putting the finishing touches on a comprehensive design template for future routes, including the Crenshaw Line, Regional Connector and Wilshire Boulevard subway.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

The “kit of parts,” as it’s known inside Metro, will dictate everything from the architecture of new stations to the design of ticket kiosks, benches, lighting, stairs and turnstiles.

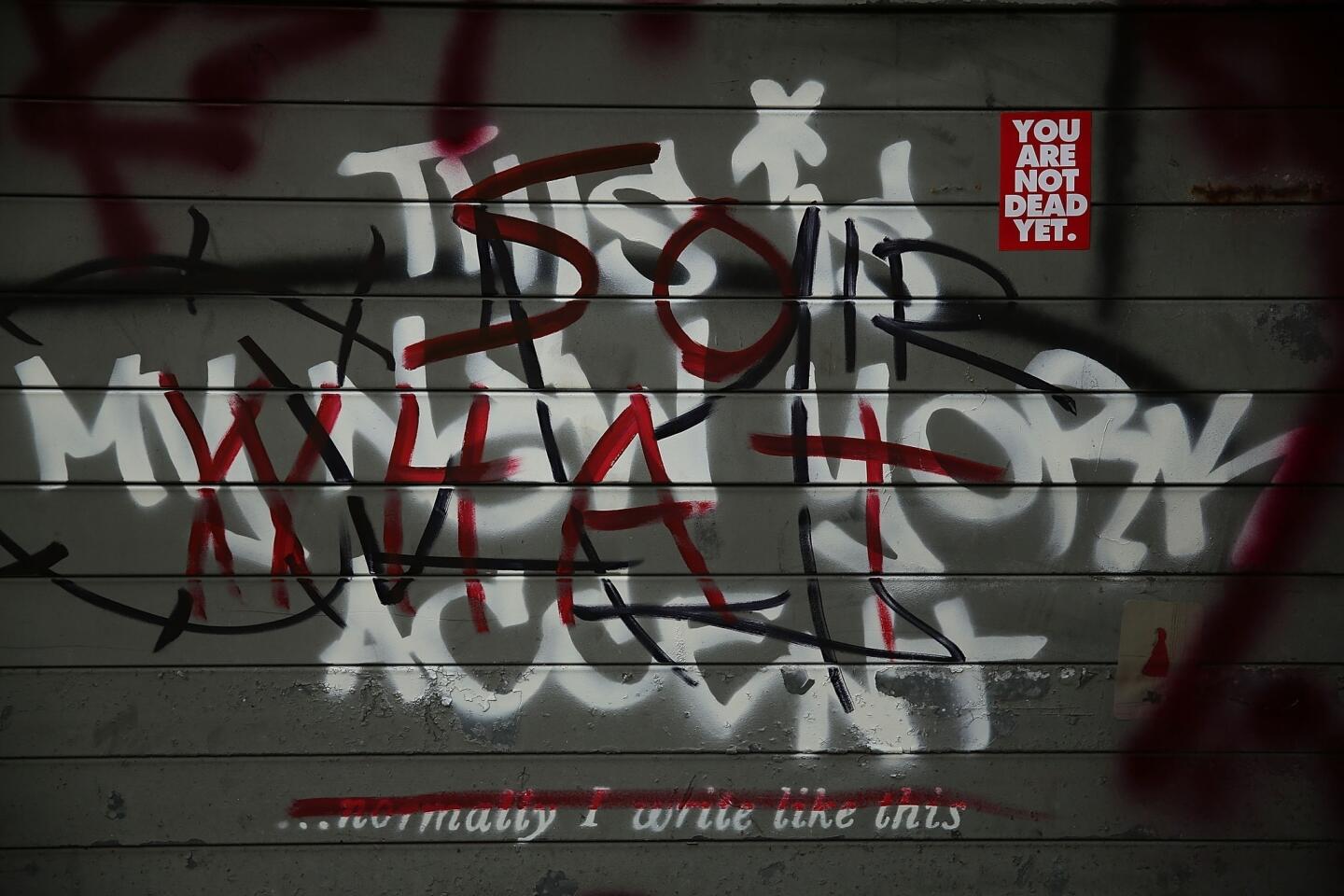

Although the spare and modern design marks a clear improvement over Metro’s wildly uneven status quo, it is also overly restrained, even bloodless. What it’s lacking more than anything is the colorful, informal exuberance that has always animated the most significant L.A. architecture and design.

And the way the new template will be rolled out suggests some of the practical obstacles that continue to dog Metro. Even in the best-case scenario it will be at least a decade before the inconsistencies in station architecture across the transit network are significantly ironed out.

The initiative is largely the brainchild of Martha Welborne, an architect who was named Metro’s executive director of Countywide Planning in 2010. The approach to designing and building stations that she inherited somehow managed to promote both wasteful spending and sub-par architecture; it was more kit of pork than kit of parts.

Some routes, such as the Expo Line to Culver City, used a consistent station design but didn’t match earlier lines. Others, like the Red and Gold lines, used different architecture for each station, often in an effort to drum up community support for new transit routes. That gave us a parade of clichés: film reels on the ceiling in Hollywood, neo-pagoda architecture in Chinatown.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

Not only were many of the stations disappointing architecturally in their own right, they didn’t coalesce into a meaningful larger whole or help symbolize the dramatic expansion of mass transit in Los Angeles. (With more than 75 stations in the planning pipeline, Metro is essentially doubling the size of the rail network in less than 20 years.) And when every station on a given rail line is different, upkeep can be a major headache.

The solution was as obvious architecturally as it would prove to be difficult politically inside Metro, where the ability to dole out elaborate design packages for new stations had become a valuable bureaucratic chip: Make the stations uniform.

Once Metro had selected Johnson Fain, Welborne and the firm’s architects, led by Scott Johnson and Brian Knight, studied the best examples of subway and light-rail architecture around the world. They came away particularly impressed with the stations in Zurich, Copenhagen, Singapore and Washington, D.C., among a handful of other cities where the transit architecture is both ambitious and consistent.

The architects also took on the slippery task of defining and even categorizing L.A.’s sense of place. They collected and analyzed some of the quintessential images of the city and its architecture: David Hockney’s paintings of the Pacific Design Center and Mulholland Drive; museum installations by Robert Irwin; photographs by Julius Shulman of houses by Richard Neutra; John Van Hamersveld’s poster for the movie “Endless Summer.”

Next Johnson Fain got to work designing a standardized version of pretty much every element that goes into a new Metro station, including signage, lighting and furniture. The architects brought in graphic design firm Sussman/Prejza and landscape architecture and planning firm Melendrez as consultants.

INTERACTIVE: Tour Los Angeles’ boulevards

Complicating the task has been the diversity of the station types Metro is now in the business of building. The Crenshaw light-rail line alone will include elevated, ground-level and below-ground stations.

For the elevated and ground-level stations, Johnson Fain has produced a linear design in which a series of gates or portals are topped by a glass canopy that operates as a kind of spine.

It’s here that the architects’ minimal approach pays the most obvious dividends, with a design that is simple and open to the city around it. At the same time, happily, sun and rain protection should be better than in many of the existing open-air stations. Maintenance should be easier too.

Portals leading to below-ground stations, including stops on the forthcoming Wilshire subway, would stretch a wide glass roof above a transparent pavilion held up by stainless steel columns.

The rollout of the new station design will be uneven. Extensions to both the Expo Line and Gold Line are being built by outside contractors and won’t use the template.

Metro has also been adding huge new canopies to the entrances to various Red Line subway stations. Their design, by the firm STV, predates the kit of parts too.

PHOTOS: Operas by Philip Glass

It’s possible that over time existing stations — on the Blue Line, say, which opened in 1990 — will be rebuilt to match the Johnson Fain design.

A separate issue, as Metro begins to consolidate the design and construction of new lines in-house, is the general restraint of the new template. Welborne is fighting the good fight, to be sure.

But the Johnson Fain design is more Apple Store neo-Modern than suggestive of contemporary Los Angeles. The architects have settled on a sleek, passive transparency to underscore Metro’s new architectural message of consistency and efficiency. All that work analyzing L.A.’s sense of place has had a faint effect on the ultimate design.

It would be a pity if the new stations, in an effort to avoid some of the architectural missteps that have plagued Metro in recent years, were content to recede entirely into the background.

Public art in the new stations may also help, though I would hate to see architecture let off the hook quite that easily. Quintessentially L.A. design elements should be incorporated into the kit of parts from the start, rather than being treated as something to be tacked on.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

A budget-conscious architectural approach doesn’t have to mean a placeless or sterile one, as L.A. architects past (Charles and Ray Eames, Cliff May, Rudolph Schindler) and present (Barbara Bestor, Hank Koning and Julie Eizenberg, Frank Gehry) have made clear.

An irony here is that the efficient, mostly black-clad Zurich stations by architect Kai Flender, a clear inspiration for the kit of parts, are noticeably less neutral, despite their Swiss pedigree, than the Johnson Fain design.

Meanwhile, the kit of parts has already faced enough challenges inside Metro to suggest how politically complicated it can be to pursue bold design at an agency of its size. To pick just one example, Sussman/Prejza suggested giant Ms, appearing to be partially sunk into the pavement, to mark the entrance to every station.

The letter would have been split into two parts, allowing it to operate as a sort of alphabetical gate. But some Metro officials balked, according to Welborne, fearing exiting passengers might have their view of cars and moving trains blocked by the giant signs.

The loss of the oversized M is emblematic of the various ways in which the kit-of-parts design risks being diluted before we see it in built form. The new stations, after all, don’t need less color or verve. They need a good deal more.

It also suggests the importance of baking a stronger L.A. flavor into the station design from the start. What’s native to the architecture, rather than what’s added around its edges, will be much harder to trim from the final product.

christopher.hawthorne@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.