In her photos, Ishiuchi Miyako focuses on the dynamics, tensions of postwar Japan

- Share via

There are two Ishiuchi Miyakos. One who followed a relatively conventional path for a Japanese woman of her generation (born 1916) — marriage, children, some work outside the home to help support her family. The other Ishiuchi, her daughter, made herself into something of an appropriation and reinvention of the first.

Born in 1947, the year of Japan’s “peace constitution,” Fujikura Yoko took up photography in 1975. She assumed her mother’s maiden name as her professional identity, superimposing an autonomous, self-determined postwar life upon one prescribed by tradition.

Ishiuchi gained recognition immediately for her work, earning honors extremely rare for a woman in Japan’s then-overwhelmingly male photographic sphere. In 1979, she was included in the exhibition “Japan: A Self-Portrait” at the International Center of Photography in New York, the lone woman among 18 men. In 2005, she represented Japan at the Venice Biennale. Now, the Getty Museum presents her first major show in the U.S., the deeply affecting “Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows.”

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter >>

Tightly curated by the museum’s Amanda Maddox, the show spans nearly 40 years. Roughly one-third of the 120 prints on view are in the Getty’s collection and constitute the largest holdings of the artist’s work outside of Japan. Maddox has thoughtfully paired “Postwar Shadows” with an engaging exhibition of five younger Japanese photographers, women who owe much to Ishiuchi for their place in a field she greatly expanded.

Ishiuchi’s family moved when she was 6 to Yokosuka, a port city where the U.S. had established a major naval base in 1945. In 1966, she enrolled at an art university in Tokyo, first studying design, then textiles. She joined student barricades in ‘69, established a revolutionary craftsmen’s association, as well as an activist group dedicated to women’s sexual independence. Leaving school without graduating, she held a variety of jobs before acquiring some photographic equipment through a boyfriend’s aunt.

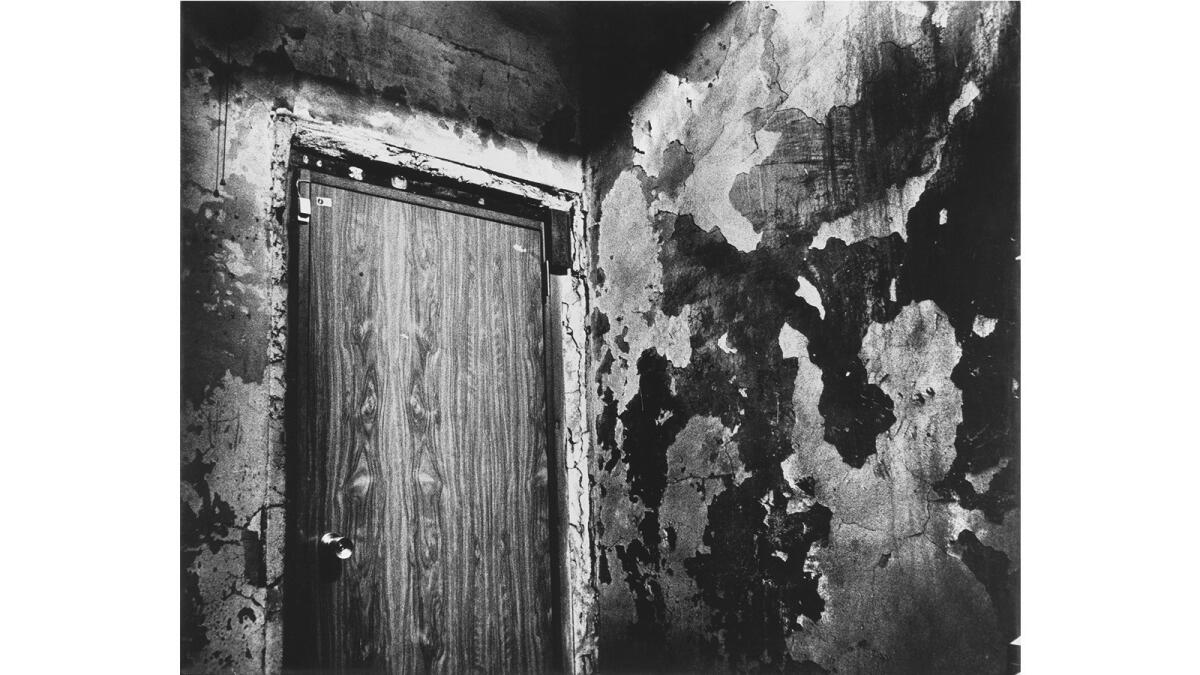

“Apartment #55,” a 1977-1978 Gelatin silver print by Ishiuchi Miyako, is part of the “Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows” show at the Getty Center.

Her first effort with a camera was a sober inquiry into Yokosuka, both the external landscape permeated by the American military presence and her own brooding memories of the place, tainted by fear and disgust. Extracting pictures from this reencounter was, she recalls in the exhibition catalog, like “cough[ing] up black phlegm.” Dark in spirit those images are, quietly harrowing cinematic stills. Their grain is thick, insistent, a veil of psychic soot.

A wave of Japanese photographers that emerged a decade prior, Daido Moriyama perhaps the most prominent among them, laid the groundwork for Ishiuchi’s work in Yokosuka. All were reckoning, with grit and raw urgency, with their country’s occupation, the insidiousness and seductions of Americanization, Japan’s metamorphosing culture and economy.

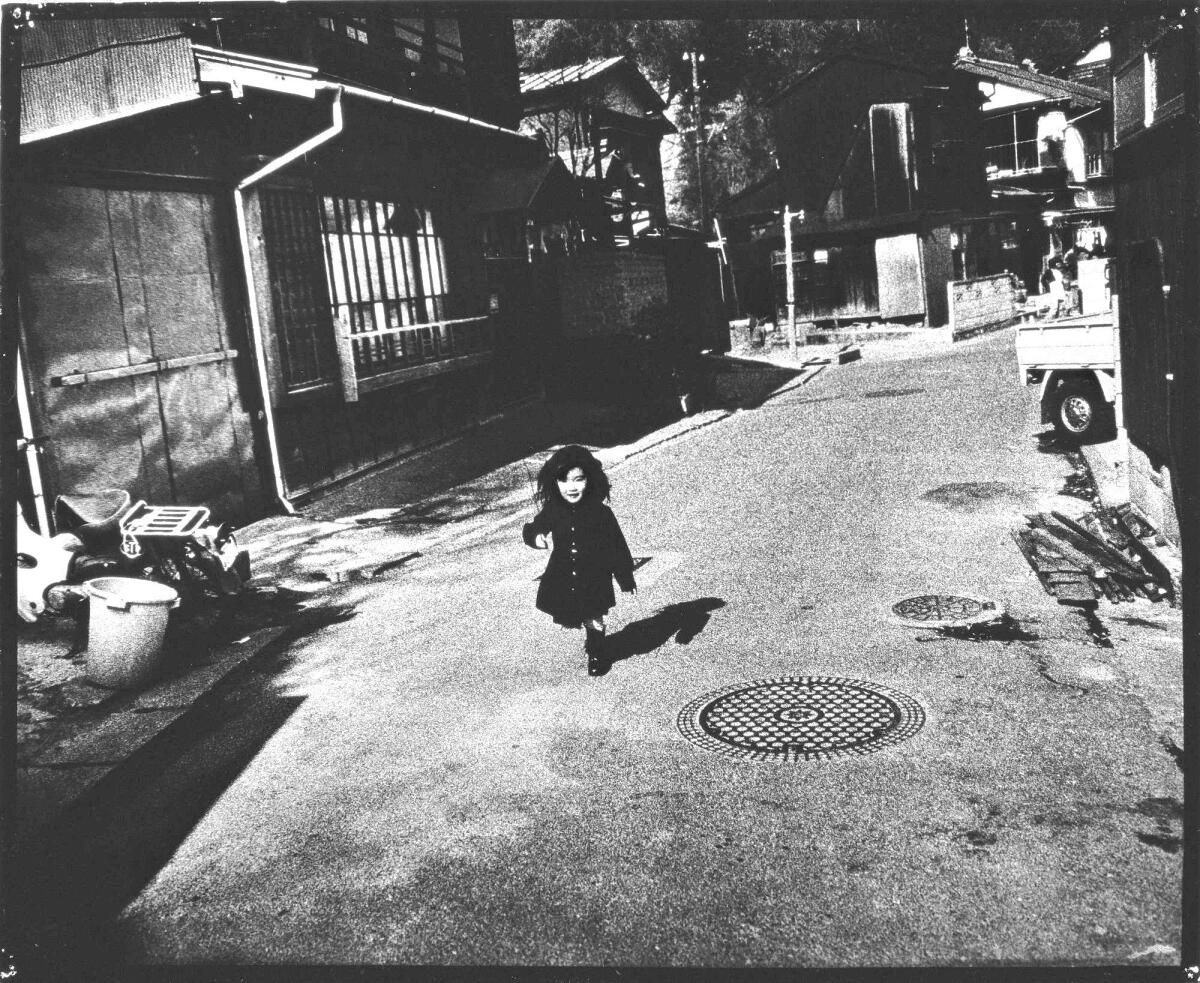

Ishiuchi made manifest this dynamic instability as well as her own enduring internal tensions, printing in intense contrast and tilting the horizon. In one image from Yokosuka, a hulking warship slants against the shoreline, a dark, daunting double of the land askew. In another, a tipped-up city street spills toward us an impossibly pristine, doll-like little girl, echo of the young Ishiuchi, who passed a red-light district every day on her way to school.

This suggestion of surrogacy threads through all of Ishiuchi’s work, suffusing it with palpable empathy. Starting with her identification with her mother and the adopting of her name, it surfaces in pictures of lone women in the city, and of environments (like cramped, derelict apartments and former brothels) where women have suffered. In 1987, when she turned 40, she made photographs of the finely lined hands and calloused feet of other women the same age, in reverential close-up.

She followed a few years later with a stunning series of images of scars caused by accident, war and illness. In most of the large, black-and-white prints, skin fills the frame. The scars read as disturbances in the field, passages of turbulence. The scarred patch in one picture defies visual traction; the skin appears to have gone temporarily out of focus.

Ishiuchi is compelled by surfaces — whether bodily or architectural — and the histories they bear. In a sense, everything she photographs is a scar, a story of damage and its visible residue.

“Apartment #55,” a 2007 chromogenic print by Ishiuchi Miyako, is part of the “Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows” show at the Getty Center.

In her most recent work in the show (2007-14), Ishiuchi identified garments in the collection of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum that were worn by women the day the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on the city in 1945. The artifacts, photographed in color on a light box, make for bracing yet lyrical images. A dress, printed life-size if not larger, doubles as a rippling, translucent skin, purplish-brown as a bruise. Floating against white, shoulders frayed and sleeves splayed, the dress seems to be ascending; at once it is damaged skin and released spirit. It is history in the form of an individual woman’s fate.

As punctuation following Ishiuchi’s show, “The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography” is as open-ended as an ellipsis and as emphatic as an exclamation point. Women emerged onto the photographic scene in Japan in great enough numbers from the 1990s onward to qualify as a phenomenon.

Their work has been dubbed “girl photographs,” the way so much fiction by and about women is simultaneously recognized but condescendingly categorized as chick lit. The photographic work of this new generation ranges widely in form and approach, largely centering on the negotiation of identity. (What art doesn’t?)

At the Getty, each of the midcareer artists is represented by a single series. In Sawada Tomoko’s installation (modeled after a window display), she casts herself as 30 different potential brides posed in the style of studio portraits that serve as part of the formal introduction between parties in an arranged marriage. Otsuka Chino seamlessly inserts her grown self beside her younger one in old family snapshots, cajoling time into taking a provocative U-turn. What defines a life in Kawauchi Rinko’s photographs is the quiet majesty of the everyday, a succession of whispered nows.

Onodera Yuki is represented by a somewhat oblique series of portraits of secondhand clothes dispersed from a Christian Boltanski installation. Shiga Lieko’s photographs are the wonderful wild cards in this bunch. Super-flashed and hue-distorted scenes of ritual and ordinary activities in the rural north where she lives, they fall somewhere between parable and paranormal.

Work by these five ranges from tender to sly, and is clearly just the tip of the iceberg. Placing it alongside Ishiuchi’s images is an instructive reminder of just how much the situation of women and photography, and especially women in photography in Japan, has changed.

Ishiuchi the elder was raised according to the Japanese “good wife, wise mother” precept regarding women’s submissiveness as a virtue. Ishiuchi the daughter helped loosen the strictures of that gendered role through her early activism and the stature and significance of her work. The money set aside for her wedding was spent instead to pay for the publication of her first two books.

--------------------------

‘Postwar Shadows’

What: ‘Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows’ and ‘The Younger Generation: Contemporary Japanese Photography’

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Los Angeles

When: Through Feb. 21. Closed Mondays

Info: (310) 440-7300, www.getty.edu

ALSO:

‘Harry Potter and the Cursed Child’ stage play will be 8th chapter of saga, J.K. Rowling says

Dustin Yellin adds his mark in L.A. with art that’s a ‘missile for social change’

Spray-paint revolution: ‘OutsideIn’ street art exhibition opens at Art Center in Pasadena

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.