Ben Jonson, like Charb of Charlie Hebdo, sought to reduce zealots

- Share via

The massacre of the Charlie Hebdo staff can be considered as another moment in a centuries-old struggle between an artist’s right to laugh at zealots (and do something about it) and the zealot’s right to be offended by the actions of the artist (and do something about it). Beyond the almost universal condemnation of the killings, many people did debate, often heatedly, the question of what should happen when the artist’s right to mock and the zealot’s right to be offended come into direct conflict.

As it happens, this is an ancient debate. One could go back to Aristophanes, in the 5th century BC, with his mockery of the Greek pantheon in plays like “The Birds” or “Lysistrata.”

But reading through the obituaries and appreciations of the slain satirists of Charlie Hebdo and especially of its editor Charb, what seemed evident was an irrepressible desire, almost a compulsion, to strip the self-righteousness of Islamic fundamentalists and religious zealots in general of any kind of seriousness. In Charb’s posthumously famous summation, Charlie Hebdo intended to reduce Islamic religiosity to something “as banal as Catholicism.”

All this made me think of Ben Jonson and his puppets and his puritans. Jonson was the cantankerous contemporary of Shakespeare who thrived as a poet and a playwright and an irrepressible troublemaker. We are accustomed to current events being described as “Shakespearean,” but the Charlie Hebdo tragedy is decidedly Jonsonian. If Shakespeare was the peculiar genius of the age, an ever-observant man from the countryside who looked at the foibles of the world with detachment, Jonson was the city man, hot-tempered and slightly out of control, at once eager for the recognition of his betters and unable to stop himself from creating controversies. Think of Shakespeare as the Bob Dylan to Jonson’s Lou Reed.

Jonson wrote a play in 1614 called “Bartholomew Fair,” today staged only occasionally. The story concerns the misadventures of a group of bourgeois English men and women who decide to visit the titular Fair, a yearly summer carnival in London’s Smithfield.

A running theme through Jonson’s play is the topsy-turvy world of Fair affecting the most respectable characters (a judge of peace, a wealthy widow, etc.) and rendering them into foolish versions of themselves. The most memorable of these transformations is at its climax when a Puritan named Zeal-of-the-Land Busy (“they have all such names,” someone comments derisively, and historically the Puritans did have them) has a debate about satire with a character in the Fair’s puppet show.

The Puritans of the early 17th century saw themselves as a persecuted minority, so much so that a faction of them separated from the Anglican church, left for Holland and in 1620 sailed on the Mayflower looking for a new continent where they could practice a version of Christianity completely purged of what they considered idolatry and superstition. These categories included bishops, colorful church outfits and decorations, popular entertainment on the Sabbath, profane theater, images of all kinds, toys and, of course, puppet shows.

Jonson, as many other irrepressible satirists to this day (like Britain’s Chris Morris and “Black Mirror’s” Charlie Brooker), was often the target of the puritanically minded. The introductory monologues at the start of “Bartholomew Fair” rail against those who don’t understand that plays are performed “for sport” and who “indict and arraign plays daily.” Many bourgeois characters within the play complain about the self-righteousness and meddling of Zeal-of-the-Land Busy, who used to be a baker but has left his trade to attend to his visions of purging society from scurrilousness.

Zeal-of-the-Land is talked into attending the sinful Fair (it doesn’t take much persuasion) and eat pork there but quickly his righteousness forces him to denounce everything he sees. “The whole fair is the shop of Satan,” he proclaims. Gingerbread men, in his view, are “the merchandise of Babylon” and the cookie stall where they are sold an “idolatrous grove of images,” which he eventually overturns and promptly gets arrested for it.

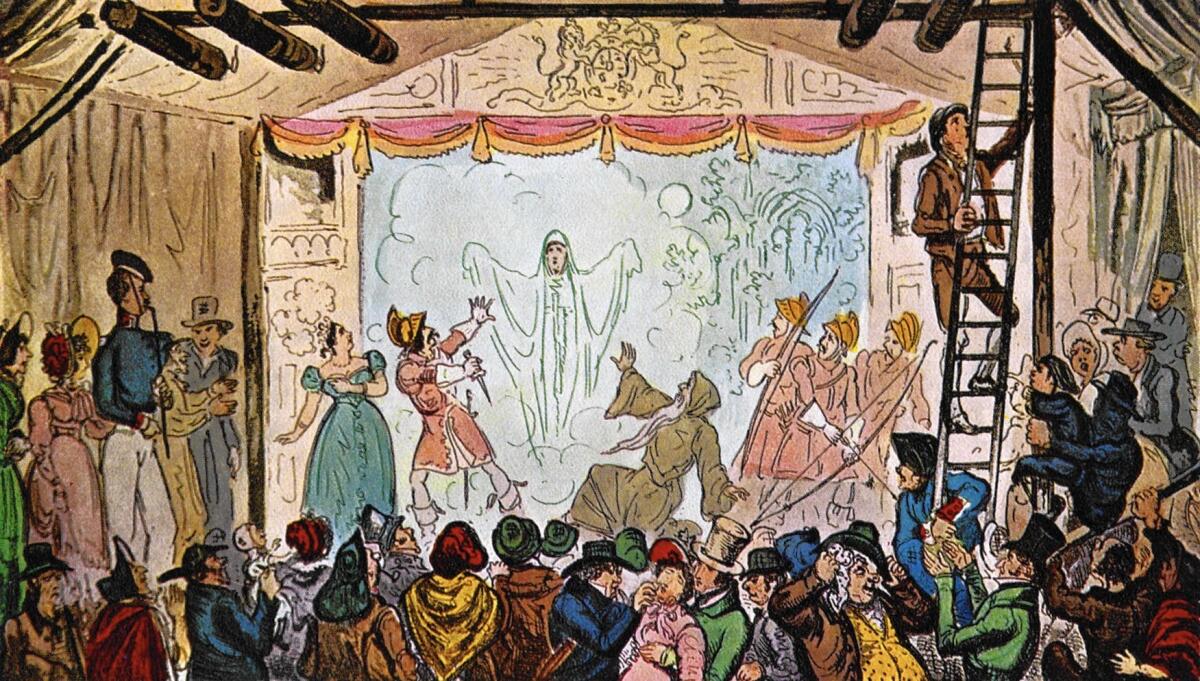

After escaping the stocks, Zeal-of-the-Land disrupts a fairly obscene, hilarious puppet show that serves as the climax of the Fair and the play. “Down with Dagon,” he screams at the puppets, “tis I, will no longer endure your profanation.” A scholarly dressed puppet then begins a learned argument with the Puritan, and Zeal-of-the-Land mentions that one of the abominations of the theater is that men dress like women and women like men. At which point the puppet lifts his garment and shows the zealot that no sexual organs are evident. Zeal-of-the-Land concedes defeat and declares himself “converted.”

The play ends with this “superlunatical hypocrite” (yes, one of his disciples also reveals that Zeal-of-the-Land’s “Puritanical brethren” group is actually a televangelist-style scam to rip off wealthy widows and orphans) being defeated by a “profane professor of puppetry” and turned into a fan of art. It’s an ending that would not look out of place on “South Park.”

Jonson, in the end, was really a disappointed idealist hiding behind an armor of satire and cynicism. And so his version of the fight between artist and zealot ends in a pro-art conversion and a communal dinner, not a bloodbath.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.