Half-life of a media turf tiff

- Share via

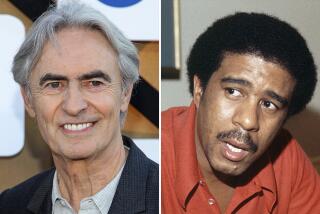

THERE was a time, not so long ago, when it felt like everyone was rooting for Marshall Herskovitz to succeed. He and longtime producing partner Ed Zwick were among the fair-haired boys of Hollywood, having produced such classy hit films as “Traffic,” as well as such critically beloved TV dramas as “thirtysomething” and “My So-Called Life.”

But that was then. Ever since Herskovitz made a big splash by co-creating “Quarterlife,” a Web drama that launched on MySpace last fall, he’s found himself in the bewilderingly unfamiliar role of an Old Media interloper, ripe to be taken down a notch. Podcasting News, for example, gleefully pronounced the Web series a bomb in December, running a chart of each episode’s views on YouTube that looked like a graph of Ron Paul’s delegate count, noting that the show was getting fewer Web views than “sleeping kitties, graffiti videos or even a clip of Sims in labor.”

That was nothing compared to what happened last week when “Quarterlife” premiered on NBC. The show was an outright bomb, with the Hollywood Reporter saying that it had earned the worst 10 p.m. time period ratings for the network in 17 years. NBC pulled the show immediately, announcing that it would finish its run on Bravo. For the most part, print critics hammered the show, dismissing its characters as annoyingly self-absorbed. Entertainment Weekly’s Pop Watch blogger Annie Barrett was equally unimpressed. “Dylan [the lead character] would be blown off the face of the planet if she existed in real life,” Barrett wrote. “Nothing about her ‘blog’ was realistic, particularly the notion that anyone would want to watch it.”

The harsh tone suggests that something deeper was at work than irritation at fiftysomething TV pros offering up a series that claimed to capture the scruffy vibe of twentysomething idealists making their way into the world. The show seems to have become ensnared in a nasty culture clash between old and new media, with “Quarterlife” serving as a magnet for Web devotees’ scorn for all the Old Media titans who’ve been invading their turf, hoping to turn the new medium into another profit center.

For years, there’s been a constant tension between Web partisans, with their idealistic belief that content should be unadulterated and free, and Old Media tycoons who tend to view the Web as a virgin world to tame, exploit and conquer. This battle has taken many forms, be it skirmishes between downloaders and lawsuit-happy record companies, clashes between netroots progressives and centrist old-school Democrats, or nasty dust-ups between bloggers and the mainstream media.

In many ways, these wars are simply another chapter in the age-old debate over purity vs. commercialism in pop culture. The Web loyalists who rebuffed “Quarterlife” are descendants of the ‘60s folkies who booed Bob Dylan for bringing the supposedly crass commercialism of rock ‘n’ roll to the Newport Folk Festival and the ‘80s DIY rock die-hards who scorned indie bands for signing with soulless record conglomerates.

Not that Web purists don’t have justifiable worries. Old Media invaders are everywhere. News Corp. and Viacom are challenging YouTube with Hulu. Veoh, another YouTube competitor, counts Michael Eisner, Tom Freston and Jonathan Dolgen among its investors -- it was also Eisner, the former Disney czar, who produced the hit Web series “Prom Queen.” One of my favorite Web series, the mockumentary “Mo Cap, LLC,” is produced by a digital studio run by Albie Hecht, former head of Nickelodeon.

“There’s definitely a lot of tension out there,” says Freston, a former top executive at Viacom. “The bloggers all attacked Arianna Huffington when she started the Huffington Post because she came from Old Media -- it was like trying to break into the cool crowd in high school. The Web doesn’t want a lot of bold-face names showing up on their turf. It was probably a liability that ‘Quarterlife’ was created by smart TV writers. It might have done better if people thought it was created by a couple of young guys in their underwear.”

The Old Media titans aren’t shy about reminding Web upstarts that they’ve got a lot to learn. Interviewed recently by NewTeeVee, Eisner said, “If Old Media includes Greek mythology and Shakespeare and Eugene O’Neill and ‘Happy Days,’ I’m thrilled to be coming out of Old Media, because Old Media means you understand motivation and character and where the denouement goes.”

Herskovitz admits that he had no idea how much bashing he would encounter. “There’s been an extraordinary amount of negativity surrounding the project,” he told me the night after its disastrous NBC premiere. “It mostly came from the people who had a sense of proprietary claim to the Internet and resented us TV guys coming onto their turf, saying we were going to do something new on the Internet.”

It didn’t help matters that Herskovitz launched the show on MySpace last fall in a classic Old Media way, with a giant publicity blitz trumpeting the fact that Herskovitz and Zwick were making it with their own money. To me, it was a sign of Herskovitz’s idealism, but it didn’t play that way on the Web, where almost everyone sniffed that the series that was supposed to revolutionize the Web had originated as an ABC-TV pilot.

To add insult to injury, Herskovitz wrote a piece in Slate just before “Quarterlife” arrived on NBC that offered a brutally honest analysis of Web entertainment, so honest that it was widely interpreted as an arrogant dismissal. “Most of it is simply incompetence and ignorance masquerading as an ‘Internet style,’ ” he wrote. “And until now no one had tried anything that would actually engage the emotions of an audience.”

Herskovitz’s implication that the Internet needed a pro to bring true drama to the barren digital wasteland provoked a new fusillade of ridicule. When I asked Herskovitz if he regretted being so blunt, he answered: “I wrote that article in a tone that in some way acknowledged the tone I see in Internet discourse -- a cheeky, in-your-face tone. It was sort of like, when in Rome, do what the Romans do. But in retrospect, it was a mistake.”

The irony is that what really bugged Webbies about “Quarterlife” was exactly what Herskovitz says he did in Slate -- they felt the show, with its crude, jittery camerawork and what one reviewer called “high-gloss navel gazing,” was a condescending effort to imitate a Web style instead of creating something new. The Web has a very different aesthetic from Old Media, one especially resistant to parody from outsiders.

“It’s a home-brew medium,” says Andy Bowers, editor of the Slate V online video magazine, who’s discovered that the Web is frustratingly unprogrammable, in the sense that it’s been extremely difficult to create the kind of predictably popular franchises that pay the bills in Hollywood. The Will Ferrell-fronted Funny or Die website, for example, has never come close to equaling the hits it got with its “The Landlord” video debut.

“You can have a giant hit and follow it up with something in exactly the same vein that seems just as good, and it can completely tank,” Bowers says. “That’s got to be really frustrating for professional content creators who aren’t used to working in such a lightning-in-a-bottle medium. You can’t create a business plan that guarantees investors millions of downloads for every episode. It just doesn’t work like that on the Web.”

The pace of invention on the Web is also very different. Albie Hecht says his company puts animated shorts like “Mo Cap, LLC” together in a matter of weeks, a process that could often take more than a year at Nickelodeon. “Everything is different, whether it’s the decision-making speed or the distribution speed,” he says. “You think up an idea in the morning and [story] board it in the afternoon.”

There are a thousand lessons to be learned about the mysterious ways of the Web, with thousands more to come. But the real lesson behind “Quarterlife’s” rocky reception is that the Web still has a healthy resistance to anyone perceived as an overbearing outsider. When I visited Herskovitz’s penthouse offices before the show premiered, I passed a long row of statuettes commemorating various showbiz awards. It’s an impressive collection. But on the Web, what matters is authenticity, something all the Emmys in the world won’t help you earn.

“The Big Picture” runs every Tuesday in Calendar. E-mail questions and ideas to patrick.goldstein@latimes.com.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.