Muslim Call to Prayer Stirs a Midwest Town

- Share via

HAMTRAMCK, Mich. — These are the sounds of Caniff Street on a windy spring afternoon:

Shrieks and giggles from children bouncing a playground ball. Chimes from the St. Ladislaus Catholic Church bell. The thump of rap music. The rumble of a Doritos delivery truck. The shrill of a teacher’s whistle, calling kids in from recess.

Later this month, another sound will join the Caniff Street cacophony: The azan, or Muslim call to prayer, will echo five times a day from the scuffed beige building across from the church.

“Allahu Akbar,” the mosque’s president will intone. Allah is the greatest.

“Ashhadu allailaha illallah,” he will sing into the loudspeaker. There is no other God but Allah.

The City Council in this community of 23,000 last week approved the mosque’s request to amplify the traditional call to prayer. The imam says the chant, which lasts about a minute and a half, will be heard for a block or two at most.

“It’s beautiful music, really, a very good rhythm, and the meaning is good,” said Abusayed Mahfuz, a member of the mosque. “I don’t see why there should be a problem.”

But the council’s unanimous decision has touched off anger, and fear, in this historically Polish Catholic town.

“With so much going on in the world with terrorism, people are afraid maybe they’ll be saying things [in Arabic] that we don’t understand,” said Marti Sharp, 47, a bakery manager.

“If they’re going to say it out loud, at least they should say it in English,” added co-worker Kathy Trusick, 60.

Circulating a petition to overturn the council’s vote, some residents insist their sole objection is the noise. Others raise more fundamental concerns: It’s not right, they say, for a patriotic Midwest city to ring with praise for Allah.

“I’m not a bigot. But as an American citizen, I shouldn’t have to have someone else’s religion constantly called to my attention,” said Bob Golen, 68.

“If you want to pray, wonderful,” said his wife, Joanne, also 68. “Do it in your mosques. Do it in your homes. But don’t bring it to my front porch. Amen.”

Settled by Polish immigrants who came to work at the Dodge automobile factory that opened here in 1914, Hamtramck has long taken pride in its ethnic flavor -- its polka music and pierogi and Polish bakeries loaded with sugar-dusted pastries.

“A touch of Europe in America,” folks here liked to say.

In the last two decades, however, new immigrants have flooded Hamtramck. They’re drawn by the location -- five miles from downtown Detroit -- and by the inexpensive real estate. The houses are weathered and packed so close together, there’s barely room for a few inches of grass between neighbors. But they’re solidly built with inviting porches, and they’re often priced at less than $75,000.

By the 2000 census, just 23% of residents indicated Polish ancestry. Nearly 10% said they were of Arabic origin. Another 10% are Asian -- half of them Indian -- and 15% are black.

Many in the city have worked hard to accommodate and integrate the new arrivals. King Video now stocks rows of DVDs in Albanian, Arabic, Polish and other languages. The public library carries the children’s fable “The Giant Turnip” in Bengali, Polish, Arabic and Serbo-Croatian. A poster for subsidized preschool is translated into nine languages.

At the Envy Me hair salon, barber Tyrone Hanes says the Bangladeshi Muslims who worship next door are “pretty cool people” -- and loyal customers too. Ali Qayed, a Yemeni immigrant who runs the Get & Go convenience store, jokes easily with shoppers of all ethnicities. And while Lyman Woodard, 28, doesn’t have many Muslim clients in his tattoo parlor, he says he feels at home amid the new arrivals, even trying the ethnic restaurants springing up next to the sari shops and halal meat markets.

“We’ve proven that we know how to live together,” Council President Karen Majewski said.

Hamtramck has even adopted a more inclusive motto: “A touch of the world in America.”

But the uproar over the call to prayer has exposed resentment behind the harmony.

At Genie’s Wienies -- a hot dog stand that boasts in faded paint that it’s been “owned and operated by Polish Americans since 1950” -- Michelle Cieslak gave voice to a common theme.

“This is going to push out what’s left of the Polish community in Hamtramck,” said Cieslak, 40, who runs the family-owned business.

Cieslak and many of her neighbors say they can’t understand why Muslims have been slow to adapt to American customs -- though, in fact, their own ancestors still hold tightly to Old World traditions.

Even today, some elderly residents speak only Polish or Ukrainian as they browse Hamtramck’s markets for smoked sausage and potato dumplings. There’s a Polish Legion of American Veterans downtown and a mural of Krakow in Pope’s Park; several buildings are painted with red-and-white Polish flags.

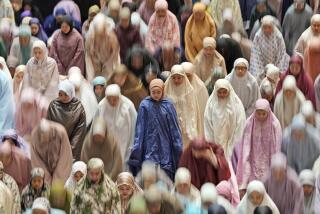

Yet some longtime residents criticize the new arrivals for clinging to their own cultural traditions: wearing headscarves, naming a Bangladeshi market BanglaTown, issuing the call to prayer in Arabic -- and then insisting that men and women worship in separate rooms.

“Why are you in the United States of America if you don’t want to become an American?” Bob Golen asked.

Worshipers at the Al-Islah Islamic Center say broadcasting the azan is not about blending into -- or defying -- the mainstream.

It’s about tradition. And sacred obligation.

In deference to neighbors, the mosque’s president, Abdul Motlib, has agreed not to broadcast before 6 a.m. or after 10 p.m., even if prayer times, which vary depending on the sunrise, fall that early or late.

Motlib acknowledges that the call to worship is not strictly necessary these days; websites list the prayer schedule. Nor does he expect to draw Muslims citywide -- not with the loudspeaker muted so his lilting chant carries only a short distance.

He’s motivated, instead, by a spiritual need to sing the invocation that Muslims the world over have called out five times a day for 1,400 years. Inviting the community to pray together, he says, brings more blessings than praying alone.

Though Al-Islah has not yet begun broadcasting -- the council’s approval takes effect May 26 -- some non-Muslim residents here are already familiar with the call to prayer.

Just two square miles in area, Hamtramck is completely surrounded by Detroit. At least three mosques just across the border in Canada broadcast the azan five times a day. Majewski considers herself lucky when she hears it: “It’s very, very soothing and spiritual,” she said.

Others, however, complain that the Arabic grates on them.

“It sounds like a bunch of jibber-jabber,” said Angela Damron, 30. She vows to move if she can hear Al-Islah’s call to prayer from her house.

“Because I don’t understand the language, it’s even more offensive,” Cieslak said.

Shahab Ahmed, who owns a local driving school, has heard such comments for years.

During his first failed run for the City Council in 1999, dozens of citizens of Arabic and Asian origin complained that they were harassed at the polls. Two residents were convicted of interfering with voters. Ahmed ran again in 2001, just after the Sept. 11 attacks. That time, he said, a flier calling him a terrorist was circulated anonymously.

Ahmed, 38, finally won election last year. As the town’s first Muslim council member, he was delighted that his colleagues unanimously supported Al-Islah’s request.

Majewski describes the vote as common sense. She says the mosque was already allowed to broadcast; by granting formal approval, the city preserved its right to regulate the times and volume of the call to prayer.

But Ahmed sees more significance in the decision. He hopes it’s a first step toward breaking down the suspicion some of his neighbors have about the new faces on their streets.

“After Sept. 11, anything people hear about Islam, they’re scared. But if they hear [the call to prayer] every day,” Ahmed said, “the fear is going to fade away.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.