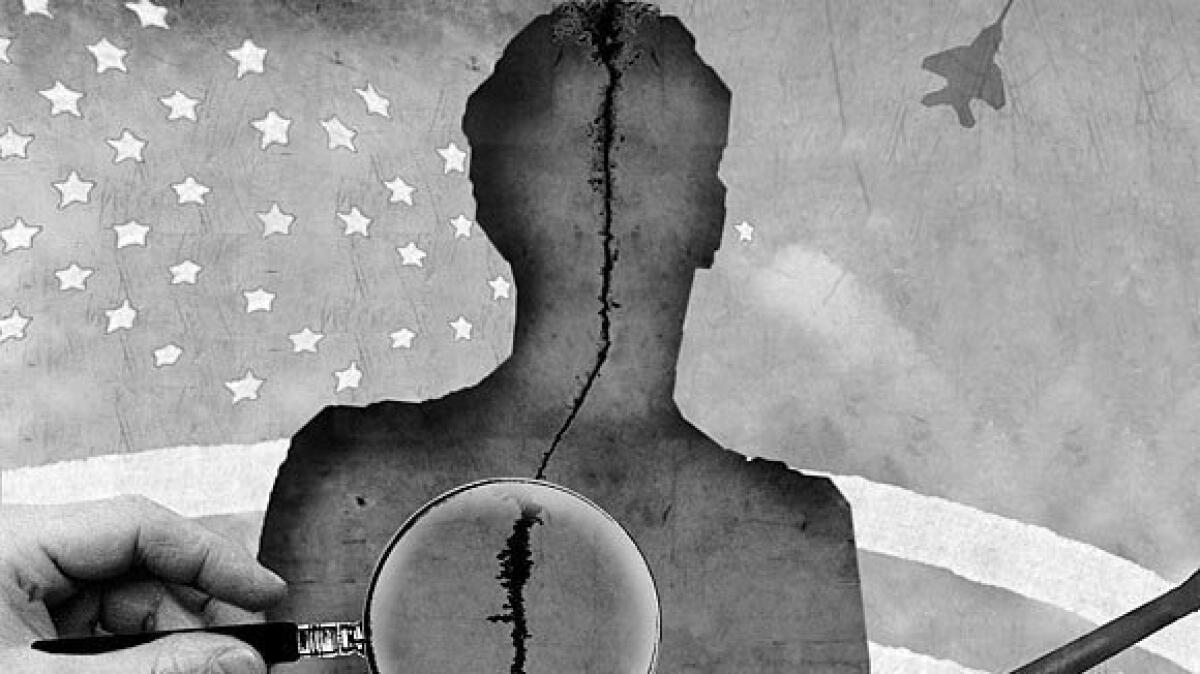

Study identifies genes linked to post-traumatic stress disorder

- Share via

Just before noon on a December morning in 1988, a magnitude 6.8 earthquake shook over 40% of the territory of Armenia, centered in the northern city of Spitak. The temblor leveled entire towns and cities, killed an estimated 25,000 Armenians — two-thirds of them children trapped and crushed in their crumbling schools — and hastened the dissolution of the Soviet Union, of which Armenia was then a part.

But the Spitak disaster was more than a geopolitical milestone. The earthquake was, in the words of one researcher, a “psychiatric calamity” that has yielded a trove of knowledge aboutpost-traumatic stress disorder.

More than a dozen studies of Spitak’s victims have helped tease out the long-term effects of PTSD and the range of factors that predispose individuals and groups to developing enduring symptoms of irritability, avoidance, intrusive thoughts and fears, vivid flashbacks and troubled sleep and appetite.

A new study of Spitak’s victims by UCLA researchers zooms in on the molecular contributors to PTSD. It finds that in Armenians who carried two specific genetic variations associated with depression, PTSD was more common.

The two genes were, by the researchers’ admission, “relatively very small” contributors to an individual’s overall vulnerability to developing PTSD. In gauging how severely a subject would suffer from symptoms 14 years after the earthquake, several easy-to-spot traits were far more useful predictors than were single-letter changes on certain genes. Among them: Females were more likely than males to experience PTSD, as were older people, those who had lost family members, and those who had experienced traumatic events before the earthquake.

But among people who developed the worst PTSD symptoms, researchers identified two DNA variants that each contributed 3% to 4% to the severity of the disorder.

A third variant was found to account for 4% of an individual’s vulnerability to depression in the wake of trauma, though no link to PTSD could be found.

The results, published Monday in the Journal of Affective Disorders, are based on a genetic analysis of 200 adults from 12 families in northern Armenia. All agreed to allow their DNA to be sent to Los Angeles, where it was combed for clues to psychiatric vulnerability.

The existence of a study population with clear genetic links, common family histories, and exposure to a single trauma allowed researchers an unusual opportunity to distill information about genes’ role in PTSD, said UCLA psychiatrist Armen K. Goenjian, who led the study. But he added that the findings needed to be replicated in larger, more heterogenous populations.

Goenjian, an Armenian American, rushed to Spitak after the 1988 quake and helped establish a pair of psychiatric clinics for victims there. Those clinics remained open for 21 years.

Goenjian said that PTSD among Armenians “was an ongoing problem and much bigger than we first appreciated,” given how widespread the destruction was, how the loss of loved ones was universal and how delays in rebuilding forced the population to confront constant reminders of their trauma.

The variants linked to PTSD were on genes that had some key things in common: Both have a role in governing the quantity and action in the brain of the neurotransmitter serotonin. And both have been found to boost an individual’s risk of depression.

Those common threads may help to explain why PTSD is so frequently diagnosed in those who have had, or who will go on to develop, depression. Serotonin is believed to play a key role in mood regulation, and many antidepressants are thought to work by boosting serotonin and its availability in the brain.

Goenjian said his team had expected to find a link between the so-called serotonin transporter gene and the severity of PTSD symptoms. But it seemed to predict only more severe depression symptoms.