Irvine’s Hoag Hospital works to bridge cultural barriers

- Share via

The nurse just thought she was bringing a refreshing dessert — a Popsicle — to a new mother. She didn’t expect the grandmother, shocked, to stop her and intercept the treat.

The cold was taboo for Shu-Fen Chen.

After emigrating from Taiwan, Chen gave birth to her first child in a Los Angeles hospital. Her cultural beliefs say a new mother shouldn’t touch anything cold for a month after birth, or she will suffer headaches later in life, she says.

Eventually, Chen moved to Irvine, home to one of the largest Chinese American populations in the nation and once home to Irvine Regional Hospital, where she had her second child. There, the nurse knew better.

“So many traditions people cannot believe,” said Chen, executive director of the South Coast Chinese Cultural Assn. in Irvine. “But some nurses just understand our culture.”

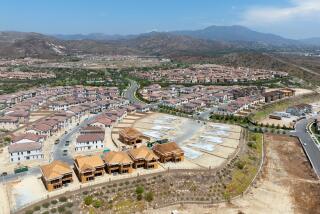

When Hoag Hospital opened its Irvine campus recently, replacing Irvine Regional, administrators hoped they had done enough to understand Irvine residents’ cultural beliefs, traditions and language.

Since the 1950s, Hoag has served mostly white and increasingly Latino patients at its Newport Beach location. Now, the hospital is stepping into a community that is nearly 40% Asian and has a large Iranian population.

Hoag has made a number of special preparations for these patients. They include creating patient rooms arranged according to the principles of feng-shui and to serving steamed rice for breakfast, and less-tangible gestures such as respectfully presenting documents with two hands and speaking to patients with more formality.

“Healthcare’s not just about your clinical ability. You’ve got to do it in a way that connects with patients,” said Robert Braithwaite, Hoag Irvine’s chief administrator. “That means understanding their cultural heritage and how they want you to communicate.”

The acculturation of Hoag was the result of dozens of meetings with community groups. Braithwaite and physicians met with the Irvine Evergreen Chinese Senior Assn.; NEDA, an Iranian Group; and non-ethnic groups including the AARP. They listened to comments about hospital plans.

Don’t have a fourth floor, some residents said, because the No. 4 is associated with death for many Chinese and Koreans, the two largest Asian ethnic groups in Irvine.

So the hospital removed the fourth-floor elevator buttons and signs during the nearly $90-million renovation of the old Irvine Regional building.

“It’s so easy to make those gestures and to be responsive,” said Sanford Smith, the hospital’s senior vice president of facilities.

He previously worked for Toyota and understands cultural sensitivity, he said.

Hoag also retained a cultural consultant and talked with executives from the Irvine Co. and the Great Park about their experiences serving people of Asian or Middle Eastern heritage.

Hoag executives are betting that clients will appreciate feng-shui patient rooms: 76% of the foreign-born Irvine residents are from Asia. An ancient Chinese practice that concerns the art and science of placement, feng shui influenced Hoag designers, the administrators said.

Even less-tangible cultural awareness could have an effect on a patient’s care — more so than landscaping and building design, experts say.

Hospital staff will need to mind how families respect their elders. Some Chinese American children might not inform parents of their illnesses to “protect” them, one research study found. Also, they could be reluctant to discuss advance directives.

Vivian Jackson, a senior associate at the National Center for Cultural Competence in Washington, D.C., said the hospital should have an ethics committee familiar with such issues and policies ready when they arise.

She said a physician might even offend a family, for example, by asking the actual patient, a mother, for direction on care, when the father or the eldest son would be the decision-maker.

“Sometimes it’s those kinds of things that can be more problematic than the substance of the actual medical care,” she said.

Hoag will use the same ethics committee as at its Newport location, and that group is familiar with cultural issues, said spokeswoman Debra Legan.

She pointed out that many Irvine residents already go to Hoag for treatment.

The food will change, though, with an added “touch of Asian” that includes vegetarian tofu stir-fry, miso soup and steamed rice with every meal.

Of course, the most important cultural factor is language.

Hoag hired interpreters who speak Mandarin and Persian. It also contracted with AT&T to provide translation over phones installed throughout the hospital. Registration materials will be in Mandarin, Korean, Persian and English.

Directional signs, though, will be in English. The instructions provided by the hospital pharmacy are printed in Spanish and English.

Language is the biggest consideration for many Chinese Americans, said Chen, of the South Coast Chinese Cultural Assn. Some Irvine residents drive to places with substantial Asian populations such as Garden Grove, where they can find small clinics with physicians and nurses who speak their languages.

A patient might not admit to her doctor that she doubts a rehabilitation plan will mend her hip replacement, if it’s customary to defer to medical authority. Then, when she goes home, she wouldn’t follow through on the directions to exercise.

The woman’s physician should coax the patient to participate in the decision-making, says Vicki Mays, a professor of psychology and health services at UCLA.

“You’re very careful not to give dictates,” she said.

Ultimately, Hoag’s cultural sensitivity may not matter as much to patients as such nuts-and-bolts factors like insurance coverage or equipment for a needed procedure.

“I think once our people have the needs, it doesn’t matter what organization operates there,” said Chen, who gave birth in the building.

mike.reicher@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.