Architect’s homework: When you can’t build it on, build it over

- Share via

Architect Todd Conversano never thought he’d be able to enlarge the 1950s ranch-style home he and his wife bought a decade ago. Two previous geological reports on the property north of Beverly Hills suggested that it would cause drainage problems or, worse, destabilize the steep slope above the lot.

But over the years, as the couple’s young son began inviting friends to play and sleep over, the need for more space away from the hubbub — specifically a master bedroom and bathroom — prompted Conversano to revisit the possibility of adding on.

Home tours: A peek inside the houses of Los Angeles >>

“We couldn’t do it on the ground without tearing into the hillside and building a huge retaining wall,” he says. “And because of the extra weight involved and earthquake requirements, we couldn’t just plop something on top of the house.”

Todd Conversano’s master bedroom addition is built upon a framework that doesn’t actually connect with the original home, other than through a staircase hidden within the aluminum siding. From outside, though, it appears to float above the house as a second story.

Indeed, second-floor additions typically require extensive and costly structural reinforcement of the existing home, two deal-breaking considerations for Conversano. Instead, he came up with a smarter, cheaper and less intrusive solution. He designed a completely separate structure that only appears to sit on the main house.

“I figured out how to do it without touching the building,” he says.

Stunning photos, celebrity homes: Get the free weekly Hot Property newsletter >>

In consultation with structural engineer Hooman Nastarin, Conversano created what’s known as a moment frame to be used as a strong, earthquake-resistant platform for the new construction. Four concrete caissons were poured deep underground (under the existing structure) and topped with steel columns tucked in out-of-the-way locations (one in the laundry room, one in the garage and two along an exterior garage wall). Steel-and-concrete beams connected the caissons below grade, and steel beams linked the columns in the air.

A side view of the home shows where the new structure rests slightly above the old structure, with the gap masked by the aluminum facade.

This tall, rectangular assemblage became the base from which Conversano cantilevered the 460-square-foot master suite over the garage, leaving a gap between the underside of the addition and the shingles on the pitched roof. Fire-resistant corrugated aluminum siding and smooth-troweled, colored stucco enclosed the gap, visually blending the two structures into one seamless hybrid facade.

Architect Todd Conversano on the staircase that leads to the master bedroom addition, a separate structure above the original house.

No one is the wiser indoors either. A staircase to the addition was carved out of former closet space, with dry wall and paint bridging and concealing the gap between old and new.

Conversano estimates that he would have spent up to 50% more on the addition had he taken a traditional route, which would have entailed more caissons and more beams. There were other savings as well. Using just four steel columns minimized demolition and reconstruction, which in turn reduced the time needed to complete the job. And because only the garage and laundry room were affected, his family was able to live at home with little disruption during the nine-month process.

“What Todd did is done in commercial projects all the time, but it’s very uncommon in residential projects,” Nastarin says. “I call it bypass surgery because he bypassed the house. The complexity of the project was offset by working around an intact building. The key was not messing with the original house.”

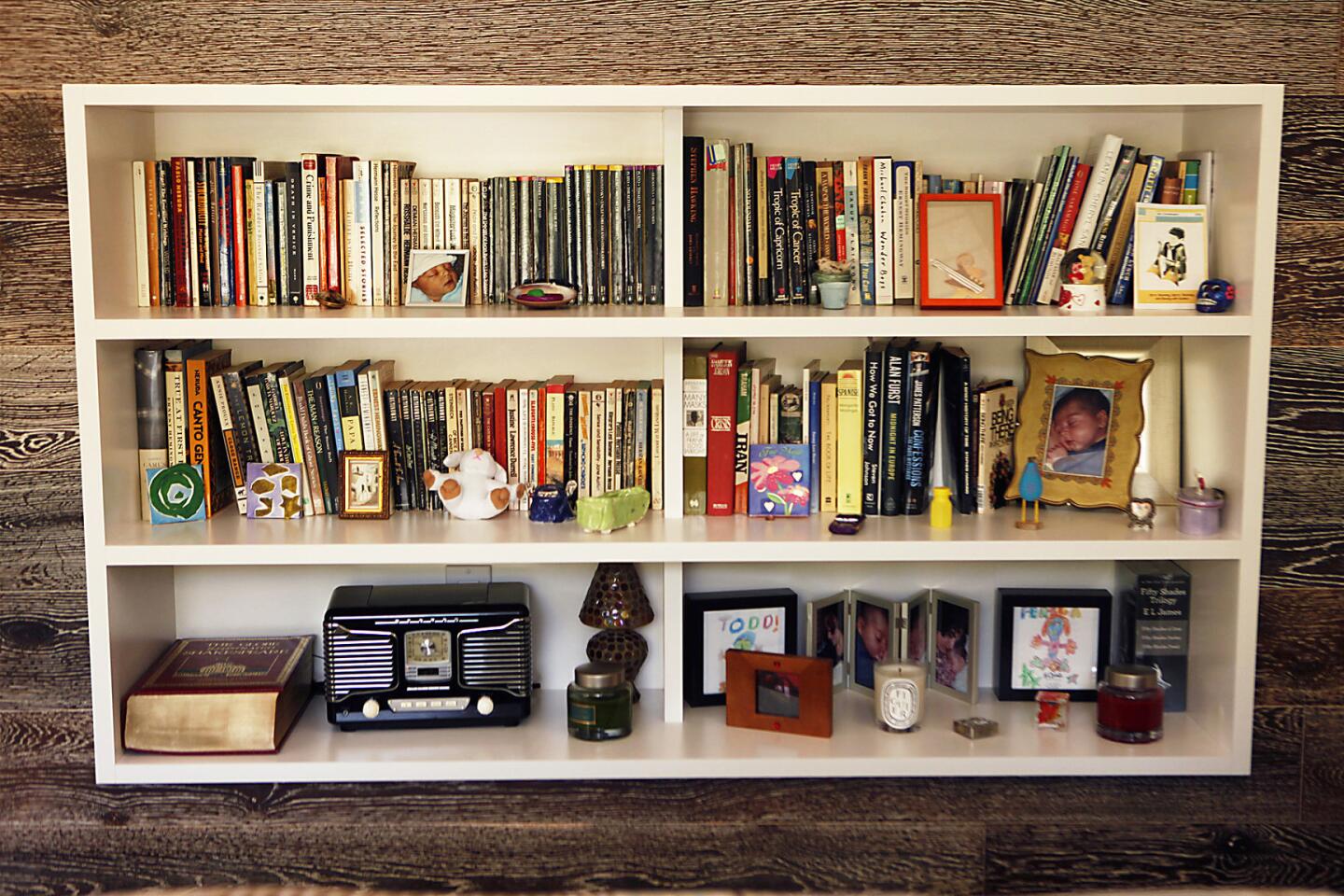

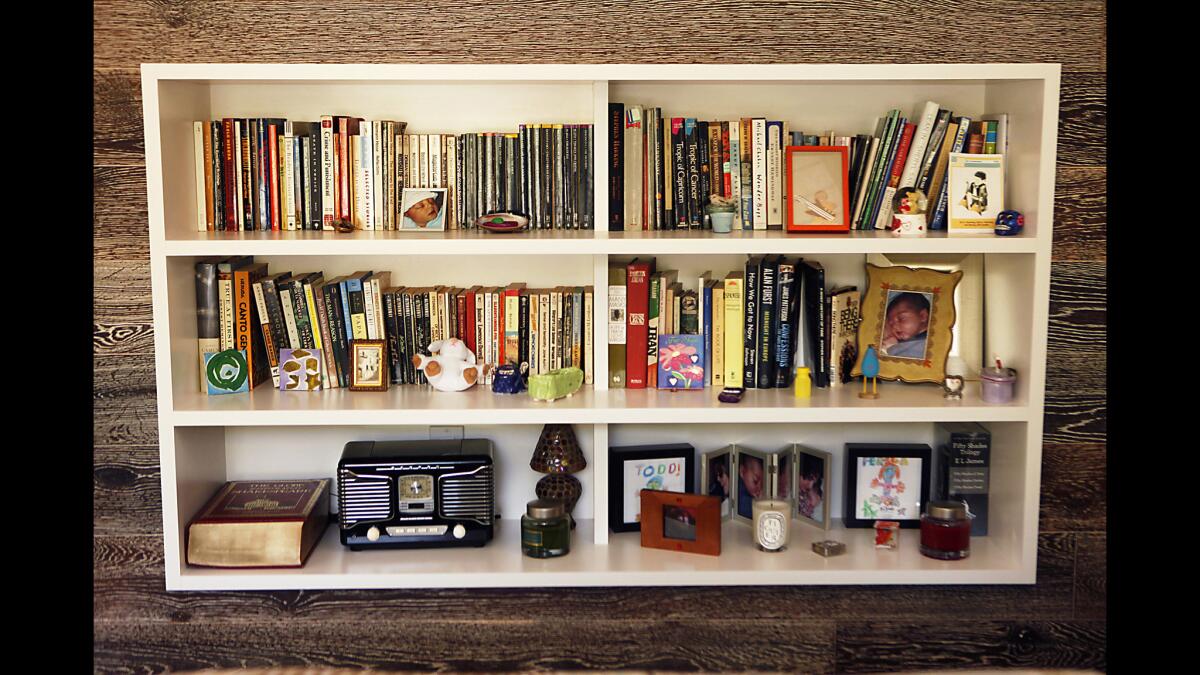

One of two built-in bookshelves can be found in the new master bedroom of architect Todd Conversano’s home.

The large new bedroom, which incorporates a walk-in closet and built-in bookshelves, features an exposed-beam ceiling and wood floors that echo details in the living room. An angled window seat aligned with the central ceiling beam brings in natural light, while glass doors in one corner of the space draw the eye past a small deck and out toward a view of the distant hills. The adjoining bathroom, with corner windows of its own, shares finishes with the bathrooms downstairs: walls of glass tile, cabinetry covered in Italian laminate and countertops of engineered quartz.

“I like that it feels similar to the old house and not foreign,” Conversano says. “It’s an updated extension, progressive but not crazy.” Sometimes two buildings are better than one.

MORE HOME TOURS

L.A. artist bends time and space in restored 1905 home

Solutions to a home-building challenge in the Hollywood Hills

Home of The Times: They found a Fickett house, bought into the neighborhood

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.