When Egypt killed the pigs, it undermined a way of life

- Share via

Reporting from Cairo — A bent man walks with a sack of garbage draped over him like a shaggy beast, hiding all but his legs as he lopes up the hill toward women and children with quick hands and shrewd eyes for spotting things of value.

The man trundles through the stink of fish, past meat hanging in the sun, slowing a bit under the weight. Trash trailing off him, he teeters around a corner and disappears into a parade of bent men. Sacks drop in sunlight and flies gather in dark, humming whirls. Hands scrape plastic, rip cardboard, but a sound is missing.

The squeal is gone.

Pigs are not to blame for the so-called swine flu, which in any case has not found this hilltop slum, but trucks flanked by armed police have come anyway and hauled them away. Raised by Coptic Christian garbage collectors who fattened them with trash and sold them to non-Muslim butchers, the animals are among the 300,000 pigs the government has ordered to be corralled and killed. Their silence means that what scant prosperity there was amid these cliffs has vanished.

“How will I feed my children now? I’ve lost 70% of my income,” says Ramzi Shawki, whose 120 pigs lived in a pen next to his house until they were driven away, sprinkled with lime and buried in trenches. “Our pigs are not sick. I can hold them in my arms. I’m 41 years old. I was born into collecting garbage and raising pigs. I’ve never been infected. But whoever doesn’t give up their pigs gets arrested.”

Up this hill, where garbage from the city below is delivered in endless strands and clumps, poor men get poorer in the neighborhoods of the zabaleen. They are Cairo’s trash collectors, tens of thousands of them, whose homes abut tiny dumps that have turned refuse into a way of life. But the swine flu scare, global economic collapses, tumbling recycling prices, all the indiscernible errors of biology and stock markets, reach deep into a man’s wallet here.

“The government gave me 2,500 pounds for my animals” -- about $450 -- says Shawki, “but they were worth 18,000 pounds.”

The men around him shake their heads. The same math has befallen each of them. They sit half in the shade, half in the sun, their trucks parked, their sacks tossed aside. There are crosses etched on the walls, and the men speak of God the way men do when the world and their own hands have failed them. They’ve been out all morning, up at 4, some lucky enough to have contracts with the tourist hotels, but that garbage has gotten lighter, as if even rich people these days are eating everything on their plates and are not so quick to throw away things that could be fixed.

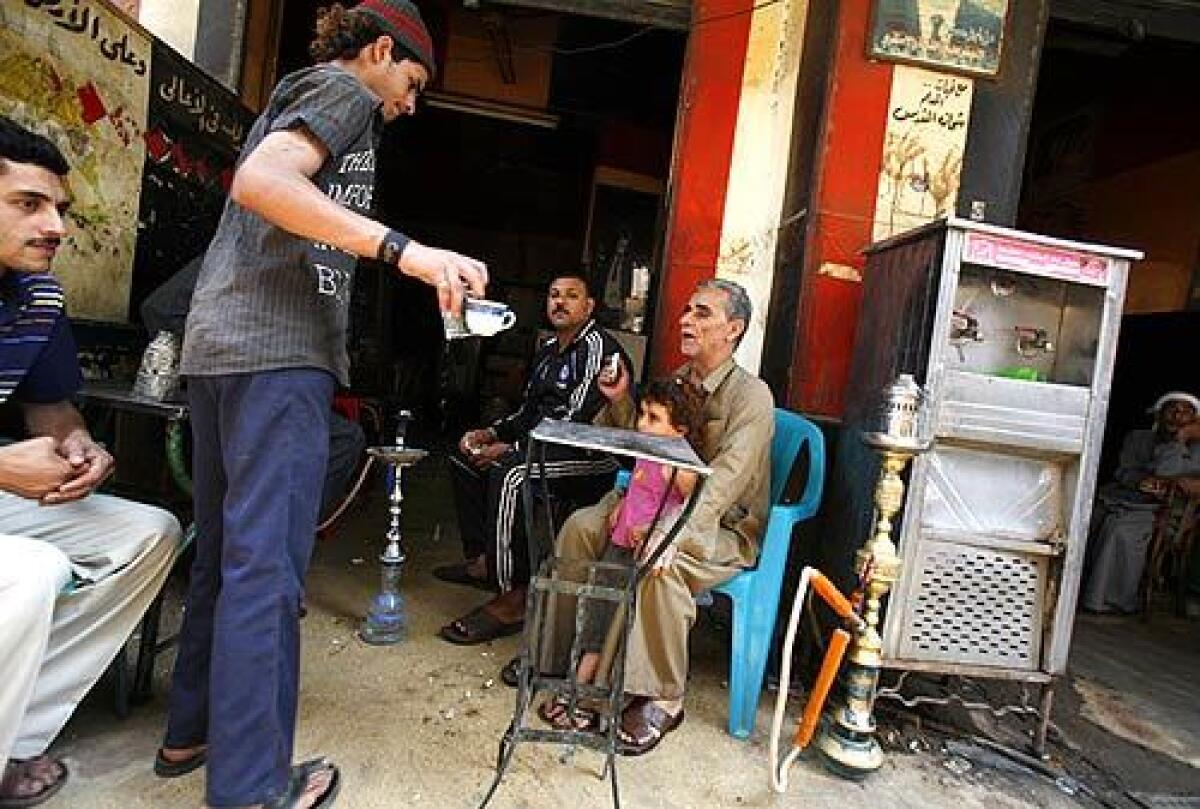

The men will go back out again later, keeping their women and children working until 10 p.m., but now it’s time for tea, rolled bread and eggs. They smoke and young boys circle; all words are weighed and faces press in. Across the way, white chickens, yanked by their wings from selling pens, squawk, and mothers wave bills at a baker who slides bread through a window.

Shawki’s uncle Mosad has an insistent voice, buzzing at the edges of other people’s conversations, breaking through every now and then with history and a fact. There used to be only tin huts on this hill. Two fires nearly burned the place down in the 1970s, but then came bricks and mortar and the neighborhood widened to where thousands of pigs ate 6,000 tons of garbage a month.

That’s what he says, but he also says the air up here is fresh, as if he can’t see the grit cloud stretching out from the cliffs over the city, which unfolds in silent chaos below. The alleys around Mosad are tight and tangled. A TV blares from a barbershop. A tailor irons in the road. Cars squeeze past donkey carts, yellow smoke spirals, and scents from chopped onions to gutted goat rise with the sun and hover well beyond the moon’s rising.

“This is not a slum,” Mosad says. “It is good up here, not like people say.”

Most of these men arrived in Cairo as boys decades ago from villages in southern Egypt. They dropped out of school and grabbed sacks, joining their fathers and uncles on new streets in new neighborhoods as the city expanded, messy and unbridled, between the Nile and the desert. They feel safe up here, but sometimes boulders shear off the brittle cliffs and smash rooftops.

Mosad and Shawki walk through an alley. Women kneel in piles of trash outside their homes, their hands smeared, but their tunics, embroidered with beads, somehow stay clean. They seem not to notice the flies, spinning in funnels around them, as tides of trash wash in to be divvied, recycled and burned. Shawki nods toward a brick wall and a girl runs through an opening to another brick wall, where she slips through a passage toward a sound that shouldn’t be here.

“We’re hiding three pigs back there,” says Shawki, a hefty man with a long, broad nose and hands made for lifting. “I don’t know what the young will do. My son ran away to look for other work, but he found nothing and came home. . . . I needed those pigs so I could marry my kids off.”

Yousef Ishaq’s eyes are rimmed dark and glow against his white turban. He’s been collecting trash since 1958. He has nine children, many of them grown, all of them in the garbage business, even Daoud, who has a university degree in commerce but can’t find an office job.

“The world’s economic problems have hit us all,” Ishaq says. “We used to sell plastic for recycling for 3,000 pounds a ton, now it’s down to 700 pounds. The government wants to contract trash collection out to larger companies and cut us out. But what they’ve done to our pigs sealed our fate.”

Daoud listens. His hair is slicked back, his T-shirt spotless. He’s supposed to get married next month. “May God help me,” he says.

A picture of Jesus hangs on the alley wall next to him. Farther down, toward the base of the hill, there are mosques and minarets. The call to prayer echoes along these cliffs, but Daoud and the other men live in a pocket of saints and crosses. It is best not to speak too forcefully about religion, but the men believe the Copts, who make up about 10% of Egypt’s population, are discriminated against and that the killing of their pigs is another affront to their faith.

“I can’t talk to this discrimination or I’ll be arrested,” says Shawki.

Mosad nods. Conspiracy coils in his mind.

Copts and Muslims have lived together for centuries. There has been occasional bloodshed; over the last 18 months clashes erupted, a Christian seminary was attacked and Copts were slain in what appeared to have been targeted crimes. The men don’t want to linger on this; it hangs unspoken among them.

“We don’t talk of religion and we don’t want civil strife,” Daoud says. “But Egypt is the only country in the world that is slaughtering its pigs over the swine flu. Ninety percent of the people in this neighborhood are illiterate. You take these garbage collection jobs away and you’ll end up with thugs and bandits.”

His cellphone rings and he walks away, followed by young men and a boy on crutches that click, click, click on the hard dirt. The sun is high. The garbage cooks. The men fix trucks and fold cardboard; plastic bottles are stamped flat and tossed into growing piles. Mosad ambles back to the shade. He’s older, silver-haired, and is offered a seat.

A bit of history, a fact.

It used to be that he earned about 90 cents a month from each house on his route. Now, he gets less than half that. And with the pigs gone, it’ll be harder getting by. Worse, even, than when he was 5 years old and he and his father left their village to make big money in the city.

Noha El-Hennawy of The Times’ Cairo Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.