Tony’s parents sent him to L.A. to treat his rare disease, but he misses Syria — and his mom

- Share via

At a time when many refugees fleeing war yearn for escape to America, Tony Alsabaa dreams of going home to Syria.

He misses his mother.

The 5-year-old, a U.S. citizen, left Damascus in August and came to Los Angeles in order to receive medical treatment for a rare disease that leaves him with infections in his spine and unable to walk without a back brace.

Tony’s Syrian mother, Maisaa Assaf, sent him to the U.S. alone in August, after she was denied a visa for a second time during the waning months of the Obama administration.

It’s now been seven months since the boy last saw his parents, and he has never met his 4-month-old sister, Emily.

Tony has juvenile idiopathic arthritis — a rare disease that leaves him sweating from high fevers and throbbing pain in his bones.

The doctors Tony visited in Syria lacked proper facilities because of the civil war that’s been raging for years, and his parents feared driving throughout the country because of bombing, said his aunt Fadaa Assaf, with whom he lives in Santa Clarita.

Now in the U.S., he takes seven medications each day; twice a month, he visits Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, his aunt said.

“He either died in Syria or we sent him here,” she said. “We don’t know what the future holds, but we need his parents to be here.”

He either died in Syria or we sent him here. We don’t know what the future holds, but we need his parents to be here.

— Fadaa Assaf, Tony’s aunt

Now, with President Trump’s new travel ban signed on Monday, his family faces an even steeper uphill battle to reunite Tony and his parents. Their plight highlights the uncertainty and confusion thousands of American families with relatives from the six nations impacted by the new order will face when it takes effect March 16, law experts said.

“To have an absolutist policy that altogether blocks people from certain countries fails to recognize the individual situations of families. Immigrants don’t live in isolation,” said Marielena Hincapie, executive director of the National Immigration Law Center.

Trump’s actions imposes a 90-day-ban on the issuance of new visas for citizens from six Muslim-majority countries: Iran, Sudan, Somalia, Libya, Syria and Yemen. Assaf, whose family is Christian, cannot reunite with her son unless she is granted a valid U.S. visa before March 16.

The new travel ban includes a waiver that experts say is one way the boy’s parents might be able to gain entry to the United States if his mother does not receive a visa before the deadline.

Waivers are decided on a case-by-case basis and would grant citizens from the six countries entry if they are visiting a close family member who is a U.S. citizen and if they can show that denying them entry would cause “undue hardship.”

Because the executive order is new, it is difficult to know how this provision will be interpreted and whether the standard of showing “undue hardship” would be difficult to meet.

“A serious illness of a child is a compelling circumstance, but it remains to be seen how they will apply the waiver provision,” said Grace Meng, senior U.S. researcher at Human Rights Watch.

The other alternative is for the boy to be returned to Syria before completing his medical treatment — a risky choice.

Since arriving in the U.S., Tony has spent almost two months hospitalized because of his condition, his aunt said.

“The disease was not recognized in Syria, and this has led to a rough course for Tony,” Dr. Bracha Shaham from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles said in a statement. “He was in significant pain and unable to walk when he was admitted in January… but is doing much better.… He will need specialized pediatric rheumatology treatment for years.”

Tony’s mother gave birth to him in 2011 when she was in the U.S. visiting family. They stayed a few months before returning to Syria.

Now Tony lives with his uncle Amil Rebz, an Uber driver, and his aunt Fadaa Assaf, who works as a cashier.

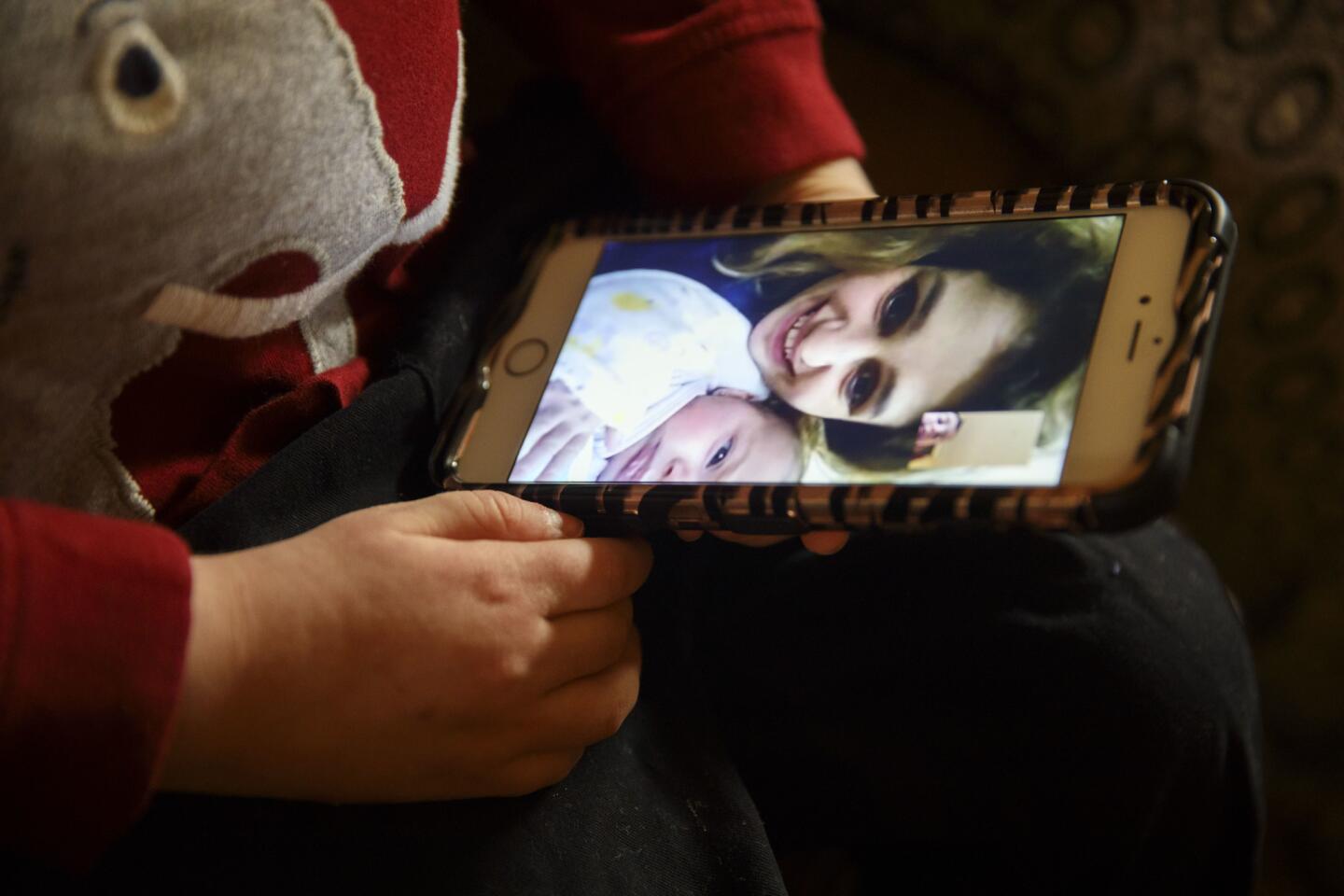

On a Saturday afternoon, Tony gripped his aunt’s iPhone and stared at the screen. His mother was on the other line, Skyping Tony from Damascus, where it was nearly 2 a.m.

Daily Skype calls over his aunt’s iPhone are the only way the boy is reminded of his mother’s face and the sound of her voice.

On this day, Tony tossed the phone on the couch and buried his head in his grandmother’s lap. His aunt handed him the phone again, and insisted in Arabic that he speak with his mother.

He started to cry.

“Sometimes he does that,” his aunt said. “Other times he’ll Skype with her for two hours nonstop.”

Follow me on Twitter @melissaetehad

ALSO

HBO’s ‘Cries From Syria’ focuses on children in refugee crisis

Op-Ed: Message from Syria to the United States: We’ll never again believe your lofty rhetoric

UPDATES:

1:05 p.m.: This story has been updated with comment from Dr. Bracha Shaham.

This article was originally published at 5 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.