What’s up with this doc? Oh, a lot

- Share via

OAKLAND — Morris F. Collen, M.D., is a pioneer in harnessing the vast power of computers to improve healthcare. He is hip-deep in studying the ways that prescription drugs could interact and harm the elderly. He’s hard at work on his sixth book.

But he just might be most proud of his brand new driver’s license.

“Can I show you something you’ll never see again?” Collen asks, reaching for his well-used billfold. He pulls out the rectangle of pedestrian plastic. He points to the date of birth: 11-12-13. He points to the expiration date: 11-12-13. He grins.

“The one is in the 20th century,” he says, tickled still. “The other is in the 21st century. That represents 100 years. When I looked at that, I said, ‘My God, that’s probably the only one in the country.’ ”

Why does a 95-year-old need a license, one that’s just been re-upped for another five years? So he can drive to work, of course.

Collen is part of an elite fraternity -- above and beyond his 11-page resume with its 193 publications and his place as one of Kaiser Permanente’s founding physicians.

Nonagenarians make up less than one quarter of 1% of California drivers. Less than one third of 1% of Americans age 95 and above work for compensation. It is difficult to discern how many work for free, and harder still to figure out how many work and drive. When Collen earned his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering in 1934, the first computer was a dozen years in the future. When he earned his medical degree five years later, penicillin had yet to be discovered.

He and Bobbie Diner wed in secret and lived apart for two years, because back in 1937 some hospitals fired nurses for marrying. Mandatory retirement was legal when Collen hit 70, so he stepped down as head of Kaiser Permanente’s Division of Research and has consulted -- gratis -- for a generation since.

The healthcare giant is happy Collen does.

“He’s doing cutting-edge research on information technology and computers,” says Robert Pearl, M.D., chief executive of The Permanente Medical Group. “He’s a systems thinker, a technologic thinker. He’s unique for a 45-year-old. He’s really unique for a 95-year-old.”

For his part, Collen is happy to pile into his 10-year-old Oldsmobile Intrigue, complete with duct tape on the right rear window, and head to the Oakland-based Division of Research every Wednesday morning.

It is an 18-mile commute from his cramped (he calls it “efficient”) unit at Sunrise Assisted Living of Walnut Creek. He spends a lot of the drive in the fast lane, zipping along at just over the speed limit.

“I do not ask for pay from KP because I want to be free to do whatever I want to do,” he said in a recent e-mail -- his favorite mode of communication. “I do what I do because I love it, and because it helps to keep the marbles rolling in my head!”

--

Seven men and one woman sit around a table in a windowless gray meeting room in downtown Oakland on a Wednesday morning in November. On the wall is a giant banner celebrating the “Morris F. Collen, M.D. Research Library and Conference Center.”

“Dr. Morris Collen continues to work at the Division of Research with Principal Investigator Joe Terdiman in development of the National Research Data Base,” the banner says. “The project is testing and evaluating data mining methods for detecting and monitoring adverse events that occur in patient healthcare.”

When the database is complete, it could house data on nearly 29 million Kaiser Permanente patients past and present, including some electronic records going back 40 years. There will be federal mortality data and census information.

Terdiman, whom Collen hired in the 1960s and has worked with ever since, calls it a kind of “one-stop shopping” for researchers.

Collen developed Kaiser’s very first database in the 1960s, a repository of electronic medical records that also was mined for research purposes. It was a time when information was collected on punch cards and computers took up entire rooms.

He was the catalyst for this latest project, which Kaiser is working on with IBM, and designed several studies to be carried out beginning in 2009 with the newly compiled data.

One in particular is near and dear to his statin-assisted heart: figuring out how elderly patients are affected by the interaction of multiple drugs.

“Every decade you add another pill,” says Collen, who takes eight medications every day. “So by the ninth decade, you’re taking about nine pills. And I used to think, gee, if I took all those nine pills and threw them into a hot cup of coffee, what would happen?

“And here I throw them into my stomach, with hydrochloric acid,” he continues. “Parke-Davis and each of them studies their own drugs. They don’t study the others.”

The regular morning meeting of the research database project has just convened, and the task this day is to revisit a question that has nagged the group for months: Whom to include in a study of bad drug reactions and their prevalence, when there will be millions of patients to consider, some with gaps in their Kaiser membership.

On the one hand, if the gap is too long, it would be impossible to know what happened to the patient during this time. On the other, if researchers are too picky, they risk missing rare but important side effects.

With the benefit of 60 years of Kaiser history stored in his balding, freckled head, Collen comes down on the side of inclusion.

He prevails.

“When I come here, I drop off 40 years; I feel like a 50-year-old,” he says after the spirited meeting. “I call this my survivor therapy.”

--

Collen has just arrived back at Sunrise Assisted Living, his home for the last two years and a place he regards with deep affection. The complex has two separate buildings: his and one for residents with Alzheimer’s disease.

“If I live long enough,” he adds with a wry laugh, “I’ll graduate.”

Here’s the bistro, where he gets his four or five cups of coffee a day. And the dining room, set up like a restaurant, where he and his pal, Pete the dentist, have meals and “watch the girls go by.”

Collen crosses the lobby and heads for the stairs. His fellow “fogies” have gathered for some live music, and the area is wall-to-wall walkers and wheelchairs. His sole complaint: Activities tend to be “spectator sports,” a little tame for a guy with a car.

Collen considers the oval second floor his “racetrack.” He has paced it out at about a block and tries to do 10 laps each day. He has stopped walking outdoors -- too much rain, too much sun.

“Here,” he says, “I just put my slippers on, and for me, it’s just perfect.”

Equally perfect is Unit 228, all jam-packed 362 square feet of it. There are two dressers, two desks, two filing cabinets, the bed he and Bobbie shared, a sofa, a coffee table, a bookcase, a television, boxes of files for his current book project.

And his computer. For Collen, the machine is equal parts tool, entertainment system and lifeline.

He is tapping out “The History of Medical Informatics: The Clinical Support Systems” on it. He uses it to watch movies, scroll through hundreds of family photos, listen to Vladimir Horowitz playing classical piano.

For the last five years he also has used it to keep in daily contact with son Barry. Barry e-mails in the morning. Collen responds in the evening. If he doesn’t, Barry calls.

So far, the system has worked pretty well, connecting the retired teacher in Rhode Island with his father in the tiny East Bay apartment. Collen is sitting in his sheepskin-covered desk chair smack in the center of the studio apartment, swiveling 90 degrees at a time and pointing out the highlights.

“I must introduce you to my family here,” he says with a wave at the pictures above his bed, a gallery that includes four children, seven grandchildren, five great-grandchildren -- and Bobbie.

“See, there’s my wife. We were married 60 years. And you know the expression ‘soul mate’? She was.”

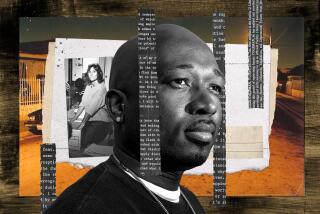

The black-and-white portrait shows a handsome woman in her 50th year, with a direct gaze and a confident smile. There is a single plastic rose taped to the frame. Collen recounts his daily ritual.

“I say good night [to Bobbie] and I say good morning,” he says, tearing up, halting. “You see that red rose? She loved red roses. And when she died, I put 60. One for each year. On her grave. Buried with her.”

Bobbie was a nurse, a poet and, as he puts it, “a piece of cheesecake!” She died at home in 1996, after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease and the dementia that often accompanies it.

Collen took care of her to the end and for the next decade remained alone in their 4,000-square-foot house on three acres.

“I’d come home and open a can of kidney beans and throw the can away, and that was my dinner,” he says. Then one night, he came down with a serious stomach ailment. He vomited and became dangerously dehydrated. One night slipped into two as he lay there, wondering whether to call 911.

“Finally, it cleared,” he recounts. “But that made me realize that living alone at my age was foolish.”

--

Collen likes to say that he inherited his father’s body and passed it along to son Barry -- the skinny arms and legs, the old man’s pot belly, the creaky heart.

Barry describes that heart as “golden”; Collen knows it requires careful attention. He also knows it is proof of the leaps medical science has taken in the seven decades since he got his degree.

“I’ll never forget when I was a young physician, 50, 60 years ago,” Collen recounts. “And a man in his 50s came in. He said, ‘You know, my father died of a heart attack at 60. My older brother died of a heart attack at 60 . . . Am I going to die of a heart attack at 60?’

“Well, his lipids were way up, and I knew he would,” Collen continues. “I told him, ‘Well, be careful, keep your weight down, exercise. And that was all, all we could do.”

It’s a story that hits home for Collen. His father, a grocer in St. Paul, Minn., died at age 67 after heart attack No. 2. When he himself was 70, he had a funny feeling in his chest.

His own physician had lots more ammunition than Collen did as a young doctor. He gave Collen an angiogram and then an angioplasty to rout out a 90%-blocked main artery. Collen has since had a pacemaker put in.

“Modern technology and modern Permanente medicine has given me 25 years,” he says. “I keep saying, you’ve just got to live long enough, and you see wonderful things happen.”

--