Op-Ed: Five Supreme Court cases to watch that could make history

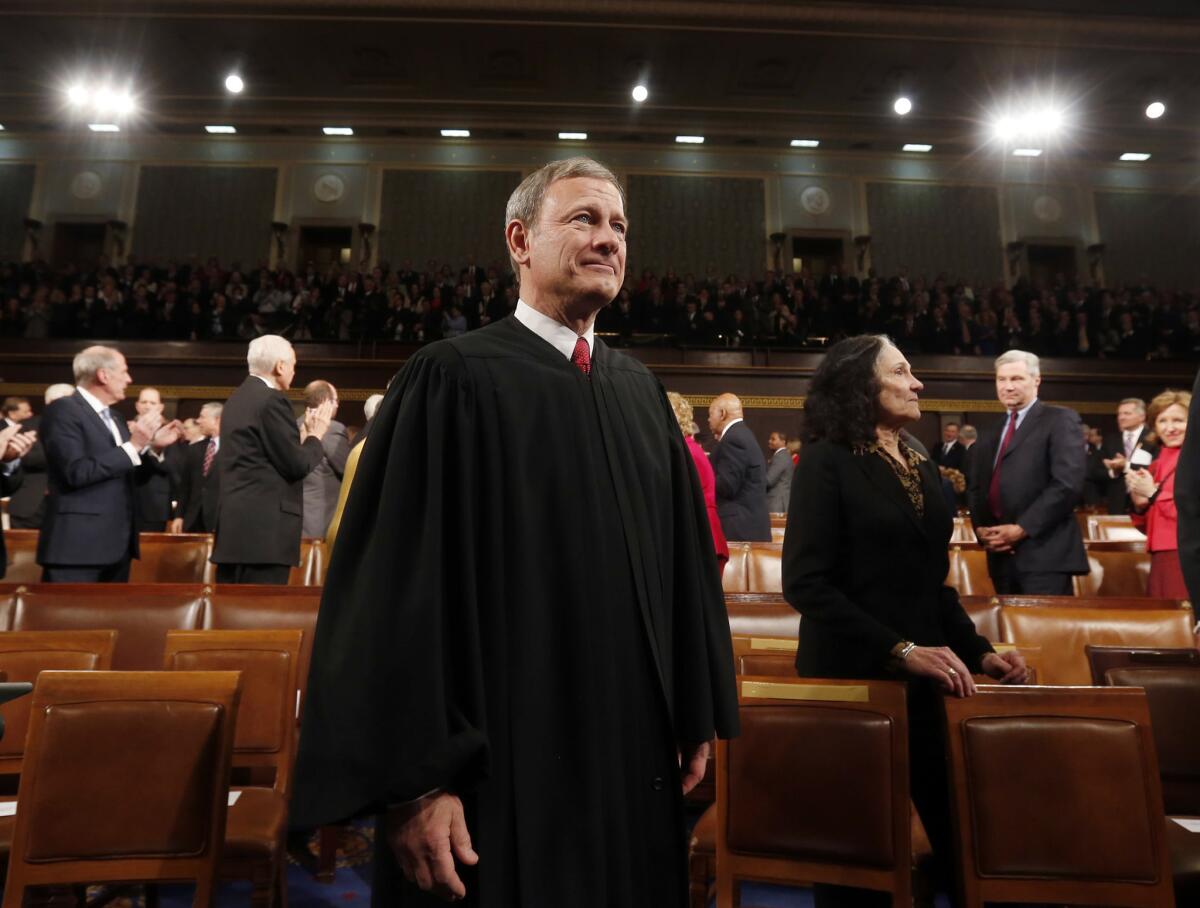

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts waits for President Obama’s State of the Union address to begin in January 2014.

- Share via

Last year the Supreme Court decided several momentous cases involving some of America’s most contentious topics, including same-sex marriage and Obamacare. The new term, which begins Monday, is also full of controversial cases that could help shape the emerging identity of the Roberts court and affect the direction of the country.

Let’s begin with organized labor. In Friedrichs vs. California Teachers Assn., the justices will revisit earlier case law — especially a 1977 case known as Abood — that allows public-sector unions to require members and nonmembers alike to subsidize the union’s political activities, unless individuals affirmatively opt out. Under Abood, even those who opt out may still be required to pay an annual fee to cover the cost of collective bargaining, or so-called chargeable services.

If, in Friedrichs, the court completely overrules the Abood line of cases (as it has hinted in recent years it might), many public employees would be tempted to free-ride. That is, they would seek to benefit from — while choosing not to pay for — the collective bargaining process, leaving public-sector unions with fewer resources to vigorously negotiate. Even if the court leaves chargeable services alone, a move from “opt-out” to “opt-in” for political expenditures could sharply reduce the political clout of public-sector unions.

Next, capital punishment. This year’s docket already features two cases centered on death penalty procedures. The more important of the two, Hurst vs. Florida, concerns Florida, one of a small number of states that allow a jury to recommend the death penalty by simple majority vote. Even then, the jury’s recommendation is advisory; the judge ultimately decides whether to impose the death sentence. It’s possible that the court will deem that process too flimsy.

There’s also a chance that the court will address whether the Constitution allows the death penalty in any case. For decades, the general permissibility of capital punishment has been firmly settled in the Supreme Court. Last term, however, Justice Stephen Breyer suggested that he might be prepared to rule it unconstitutional in all or virtually all cases. Breyer is well known as a pragmatist, disinclined to tilt at windmills. So perhaps he now thinks that the court’s pivotal justice — Anthony Kennedy — is open to a more sweeping assault on the death penalty.

Racial tension in America might be the national storyline in recent years, and the extent to which government can take account of race is, fittingly, front and center this term. In a case that has pingponged within the federal judicial system, Fisher vs. University of Texas, the court will ponder the race-based admissions policies of the University of Texas. May UT give preference to applicants who come from underrepresented racial groups?

A dozen years ago, a 5-4 majority allowed the University of Michigan law school to give a boost to ethnic minority applicants. But since then, Justice Samuel Alito, who generally frowns on affirmative action, has replaced Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who wrote the Michigan opinion. The new swing vote on this topic is no longer O’Connor, but Kennedy, who has registered strong discomfort with admissions plans that afford racial preferences to individuals.

It’s difficult to overstate the potential consequences here. The court’s ruling in Fisher might well apply not only to public universities but also to private colleges and universities that are bound to the same norms as public schools by virtue of federal funding statutes.

Voting rights are also on the docket. In Evenwel vs. Abbott, the justices will decide whether, under the 14th Amendment, each state legislative voting district must simply contain an equal numbers of people, or must instead have an equal number of voters or voting-age citizens.

This dispute, nominally about redistricting procedures, also implicates the national debate about immigrants — another 21st century flashpoint — because if states must stop counting noncitizens for representation purposes, areas with more noncitizens (which tend to lean Democratic) would lose clout. The justices could leave the answer up to the states, or do something much more destabilizing.

And for the piece de resistance, consider a case that brings together capital punishment, race and voting rights of a sort: Foster vs. Chatman.

Did the Georgia courts do their job, in a death penalty case, in ensuring that blacks were not improperly excluded from the jury box? Foster involves “peremptory challenges” — instances when a lawyer rejects a number of jurors from a case not because of any demonstrated “cause,” but based on a lawyer’s mere hunch that the stricken jurors would not be good for that lawyer’s side.

Long-standing case law prohibits lawyers from using peremptory strikes on the basis of race or gender; but lawyers do this anyway all the time, both consciously and unconsciously. In Foster, the reasons given by the prosecutor for removing all the black potential jurors were quite implausible — race was obviously the root cause — and yet the Georgia courts accepted the prosecutor’s sham excuses.

The court probably will issue a limited ruling, determining whether the Georgia courts erred in this particular case. There’s a chance, though, that Foster could open a discussion about whether peremptory challenges should be eliminated altogether.

Jury service has always been understood — in constitutional terms — as political participation akin to voting. Jurors vote — that’s what they do when they decide cases — and the voting-jury link was recognized by the framers in the 1780s, by those responsible for drafting the 14th and 15th amendments, and still later by authors of 20th century amendments that protect various groups against discrimination at the ballot box. If would-be voters cannot be disenfranchised on election day without a strong reason, why is it permissible to exclude would-be jurors from the jury box without an equally strong reason?

When the last term came to a close, right-wing politicians disappointed by Kennedy’s same-sex marriage decision went so far as to say the court’s word wasn’t law. Nothing on the docket so far seems likely to inspire that sort of white-hot conservative passion, but a few cases might come close, and in any event, in a presidential election year, anything the court does will attract intense scrutiny.

Akhil Amar is Sterling Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University. Vikram Amar is dean and Iwan Foundation Professor of Law at the University of Illinois College of Law.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.