Activist tries to rally Pakistani Americans to demand a more liberal Pakistan

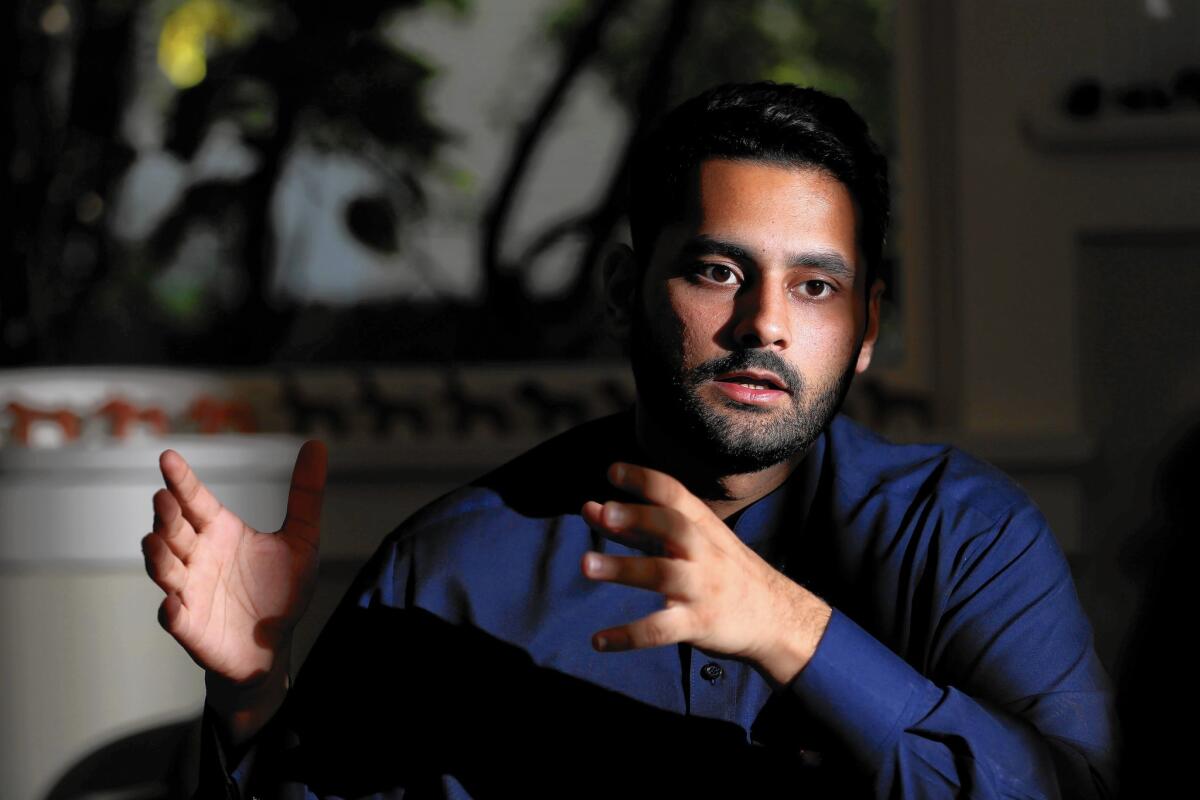

Pakistani activist Mohammad Jibran Nasir speaks at Pomona College. Nasir is encouraging young Pakistanis to join the fight against extremism.

- Share via

Mohammad Jibran Nasir said it was time for him to do his part to “reclaim Pakistan” after a bombing in his native Karachi killed about 50 people in a Shiite-majority neighborhood. Nasir is Sunni.

It didn’t matter. Or maybe it did.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

May 26, 1:49 p.m.: The caption on an earlier version of this article incorrectly said Mohammad Jibran Nasir was speaking at Claremont College. He was speaking at Pomona College.

------------

“The Sunnis won’t sympathize because someone is a Shiite,” said Nasir as he sipped from a cup of hot tea in Claremont before a talk at Pomona College. “I mourn the fact that people are not able to mourn the loss of victims. I mourn apathy.”

The 2013 bombing, designed to fan sectarian violence between minority Shiite and majority Sunni Muslims, helped inspire the 28-year-old activist to kick off a six-week tour last month of colleges and universities throughout the United States to tell Pakistanis in America that their homeland is “not a nation of Taliban apologists,” that together they could find a solution to the religious intolerance and violence back home.

He spoke at Stanford, UCLA and UC Davis, among other colleges.

“They are stakeholders,” Nasir said before addressing more than 100 Pakistanis and Pakistani Americans at Pomona College.

Nasir helps run two grass-roots groups — Pakistan for All and Never Forget Pakistan — that campaign for the Pakistani government to shut down militant extremist groups.

The lawyer turned protester said he hoped the estimated 455,000 Pakistanis living in the U.S. will support the cause and advocate for a more liberal Pakistan instead of simply donating money. With about 40,000, California has the third largest number of Pakistanis in the U.S. after New York and Texas.

“Pakistanis here can be more vocal because there is no threat to their life,” he said.

Although the number of extremist attacks has decreased in the last year, there has been an overall surge in such violence in Pakistan since 2007, said Daniel Markey, an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

A 2013 report from the U.S. State Department illustrates the point: Pakistan had the second-most terror attacks in the world that year after Iraq.

“Some of those attacks were the most devastating in terms of loss of life,” Markey said. “It’s very bad right now.”

The cycle of violence repeated itself this month, when armed men opened fire on a bus carrying members of the Ismaili community, a sub-sect of Shiite Islam, in Karachi. The passengers were reportedly traveling to a house of worship in a bus that belonged to an Ismaili welfare society.

At least 43 people were killed and 13 wounded in the worst attack in recent memory against Pakistan’s Ismailis, widely regarded as a progressive and largely apolitical community whose members are prominent in the health and education sectors.

The constant attacks are personal for Nasir, whose friend and mentor Sabeen Mahmud was fatally shot last month. Nasir was preparing to speak to Pakistanis at Columbia University in New York when he heard the news. He said he still hasn’t had the chance to mourn the loss.

“Sabeen always said, ‘You know what, I’m scared for you. But I’m not going to stop what you’re doing.... You have to die one day, but today you are living,’” Nasir recalled.

Mahmud, 40, was shot multiple times after hosting an event called Unsilencing Baluchistan (Take 2), a discussion about missing people in Baluchistan province.

Baluchistan has seen an uptick in “enforced disappearances,” in which authorities take people into custody and then deny knowledge of their whereabouts, according to Human Rights Watch.

Nasir has also been targeted himself. He has been arrested for protesting, clashed with clerics and received death threats.

In December, a devastating Taliban attack on a Peshawar army school killed nearly 150 people, including more than 130 children.

But the extremist leader of the Red Mosque, an Islamist bastion in Islamabad with ties to the Taliban, refused to condemn the attack and called it understandable.

Unable to stomach the cleric’s statement, Nasir organized a protest and took to the streets in response, rallying Pakistanis to “reclaim Pakistan” and “reclaim our mosques.”

That’s when the threats poured in, he said — from militant groups, from Red Mosque authorities and from the Taliban — warning him to tone down his activism.

“They say I am the one giving Pakistan a bad name. But I am not the one giving Pakistan a bad name,” Nasir said. “Religion can never be the root of the problem. Thou shalt not kill ... thou shalt not steal, all these things we learn from religion.”

What is corrupting Pakistan is a “perverse” mixture of Islam and politics that leads to misinterpretations of the faith, Nasir said.

“We cannot and should not legislate on how a man reaches out to his god,” he said. “Whichever god it is, it is personal.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.